University of South Carolina University of South Carolina

Scholar Commons Scholar Commons

Theses and Dissertations

Spring 2021

“The Lifeblood of College Sports”: The NCAA’s Dominant “The Lifeblood of College Sports”: The NCAA’s Dominant

Institutional Logic and the Byproducts of an (Over)emphasis on Institutional Logic and the Byproducts of an (Over)emphasis on

Recruiting Recruiting

Chris Corr

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd

Part of the Sports Management Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Corr, C.(2021).

“The Lifeblood of College Sports”: The NCAA’s Dominant Institutional Logic and the

Byproducts of an (Over)emphasis on Recruiting.

(Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/6504

This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in

Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

“THE LIFEBLOOD OF COLLEGE SPORTS”: THE NCAA’S DOMINANT

INSTITUTIONAL LOGIC AND THE BYPRODUCTS OF AN (OVER)EMPHASIS ON

RECRUITING

By

Chris Corr

Bachelor of Science

University of Florida, 2015

Master of Science

University of Florida, 2016

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in

Sport and Entertainment Management

College of Hospitality, Retail & Sport Management

University of South Carolina

2021

Accepted by:

Richard M. Southall, Major Professor

Allison D. Anders, Committee Member

Khalid Ballouli, Committee Member

Mark S. Nagel, Committee Member

Tracey L. Weldon, Interim Vice President and Dean of the Graduate School

ii

© Copyright by Chris Corr, 2021

All Rights Reserved.

iii

DEDICATION

To my wonderful wife, thank you for your unceasing support of my dreams and

our family. And thank you to my loving parents, who instilled in me the value of

education, laughter, and character.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Southall for his acceptance, guidance, and friendship. I

can’t imagine being where I am today without you. I would like to acknowledge and

thank Dr. Ballouli, Dr. Nagel, Dr. Gillentine, and Dr. Mihalik for their thoughtful

conversations and mentorship. I would also like to thank Dr. Anders for sharing her

expertise and passion for social justice. Thank you to all of you for the impact you have

had on my life.

v

ABSTRACT

In big-time college football, successful recruiting is the foundation on which

winning programs stand. Power-5 football and men’s basketball operate under a

dominant institutional logic that values generating revenue above all else. Winning

generates revenue and, accordingly, Power-5 stakeholders are often engulfed in their

unique athletic roles. The system propagates adherence to a singular focus that

emphasizes winning and revenue generation. This dominant institutional logic governing

big-time college football has been dubbed jock capitalism (Southall & Nagel, 2009).

While prominent theorists have analyzed college sports through an institutional logic

perspective, a systematic examination of the Power-5 football recruiting process has not

been conducted to this point. The three parts of this dissertation aimed to examine

components of the college football recruiting process through the primary framework of

Power-5 football’s dominant institutional logic. Findings reveal that athletic role

engulfment and racially tasked disparate roles have been institutionalized within

Southeastern Conference (SEC) football; proliferated by institutional actors (e.g.

recruiters and coaches) and adhered to by recruits and players. In the SEC, the emphasis

placed on winning football games directly reflects an institutional jock capitalism logic.

vi

PREFACE

From 2012 to 2018, I worked in various roles in the Southeastern Conference

(SEC). I was exposed to the business of college sports and inundated with National

Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) language and ideology. While working in

football recruiting I propagated this ideology, indoctrinating countless recruits and

employees into the NCAA college-sport hegemony. Just as I did, college athletes,

employees, fans and other stakeholders grow up cheering on the NCAA’s collegiate

model, accepting societal norms that perpetuate the current system. Having indoctrinated

countless recruits and employees, I experienced firsthand an environment replete with

academic dysfunction, role engulfment, and enabling behaviors. Within the institutional

field of Power-5 athletics, I was expected to accept morally and ethically questionable

practices as part of the business. Subsequently, the following studies that comprise this

dissertation were developed sequentially, with the first study informing the second, while

the third study was informed by both previous studies. In addition to all the studies being

interconnected, they also all had their genesis in the question whose answer led me to

leave the college football recruiting profession; Does college football recruiting really

benefit the recruits?

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEDICATION ................................................................................................................. iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. iv

ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................v

PREFACE ......................................................................................................................... vi

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ ix

LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................x

LIST OF SYMBOLS ........................................................................................................ xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... xii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................1

CHAPTER 2: SOUTHEASTERN CONFERENCE RECRUITING

OFFICIAL VISITS AND THE MAINTENANCE OF THE

INSTITUTION OF POWER-5 COLLEGE SPORT ..............................................6

2.1 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS ..................................................................8

2.2 RESEARCH CONTEXT ................................................................................16

2.3 METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................19

2.4 FINDINGS ......................................................................................................22

2.5 DISCUSSION .................................................................................................25

CHAPTER 3: SOUTHEASTERN CONFERENCE FOOTBALL

RECRUITING: INSTITUTIONALIZED ROLE ENGULFMENT

AMONG RECRUITERS ......................................................................................39

3.1 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS ................................................................42

3.2 METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................53

viii

3.3 FINDINGS ......................................................................................................56

3.4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION .............................................................69

3.5 FUTURE RESEARCH ...................................................................................73

CHAPTER 4: THE NCAA’S DOMINANT INSTITUTIONAL LOGIC AND

THE LACK OF BLACK HEAD COACHES IN POWER-5

FOOTBALL ..........................................................................................................78

4.1 LITERATURE REVIEW ...............................................................................80

4.2 METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................98

4.3 FINDINGS ....................................................................................................104

4.4 DISCUSSION ...............................................................................................115

4.5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH .............................................118

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION ..........................................................................................129

REFERENCES ...............................................................................................................135

ix

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1 Top-Ten Power-5 Athletic Department Revenues-Expenses .......................... 31

Table 2.2 2019 Power Conference Revenue Distribution ................................................ 32

Table 2.3 Codes Examples & Themes ............................................................................. 33

Table 2.4 Sport Findings .................................................................................................. 34

Table 2.5 Summary Statistics .......................................................................................... 36

Table 3.1 P-5 Football Recruiting Budgets, 2017-2018 Fiscal Year ............................... 75

Table 3.2 SEC Recruiters ................................................................................................. 77

Table 4.1 Racial Composition of Coaches ..................................................................... 120

Table 4.2 Background of Coaches’ Hometowns ........................................................... 121

Table 4.3 Racial Composition of Recruits ..................................................................... 122

Table 4.4 Background of Recruits’ Hometowns .............................................................123

x

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1 College Sport’s Organizational and Institutional Layers ............................... 37

Figure 2.2 Typology of College Athletic Conferences/Divisions ................................... 38

Figure 4.1 Counties with the Greatest Concentration of 5-star Recruits ....................... 124

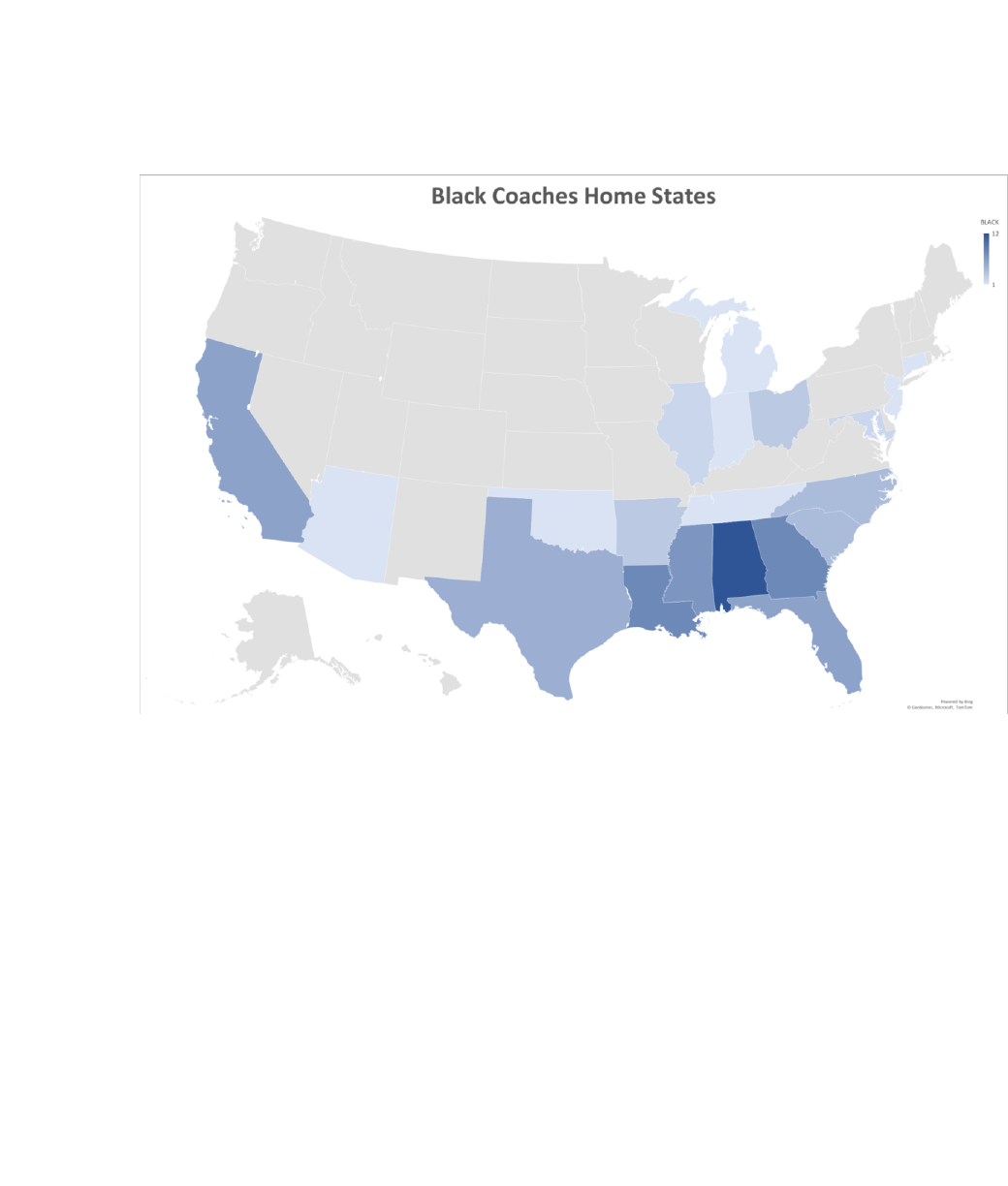

Figure 4.2 Black Coaches Home States ......................................................................... 125

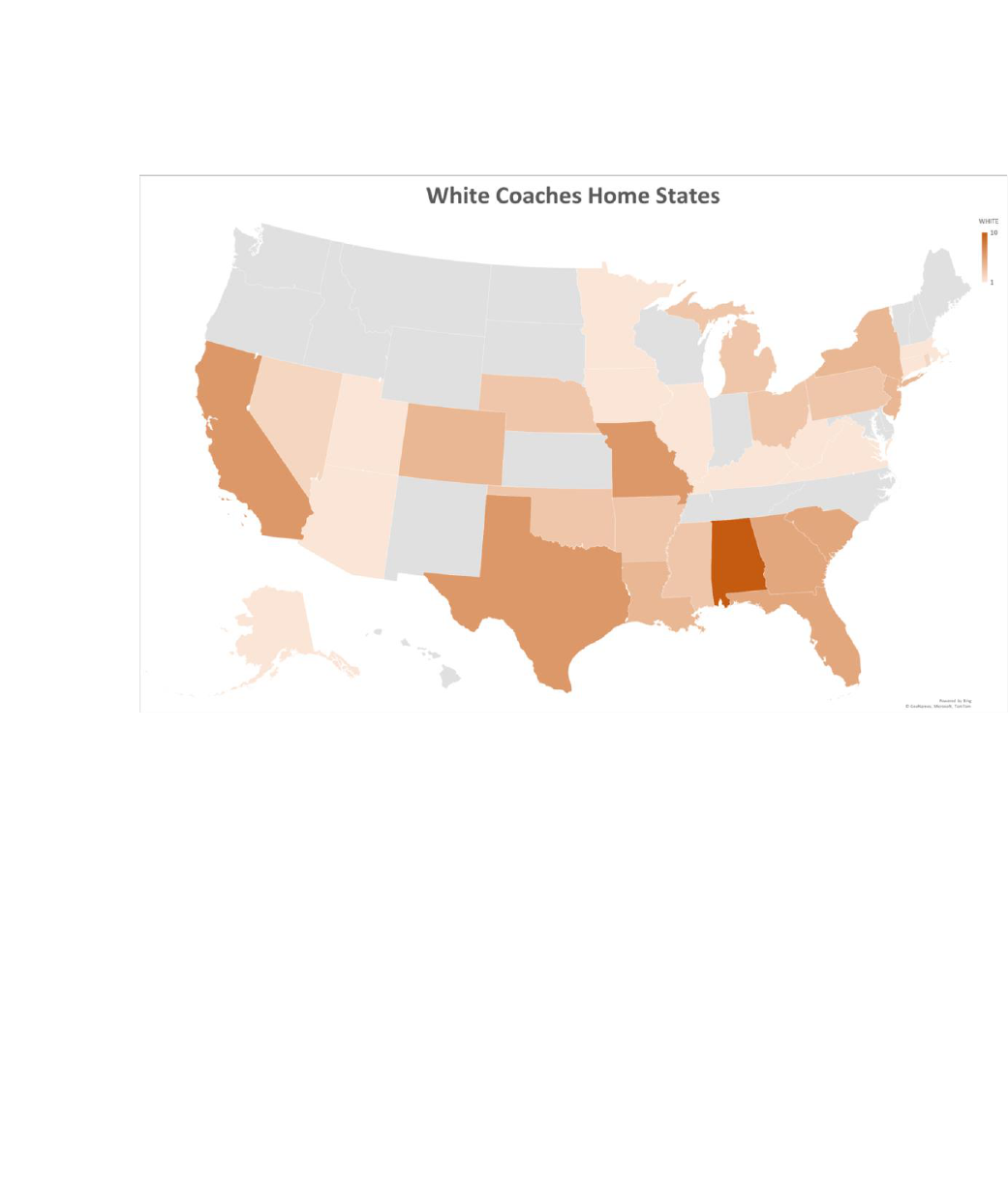

Figure 4.3 White Coaches Home States ........................................................................ 126

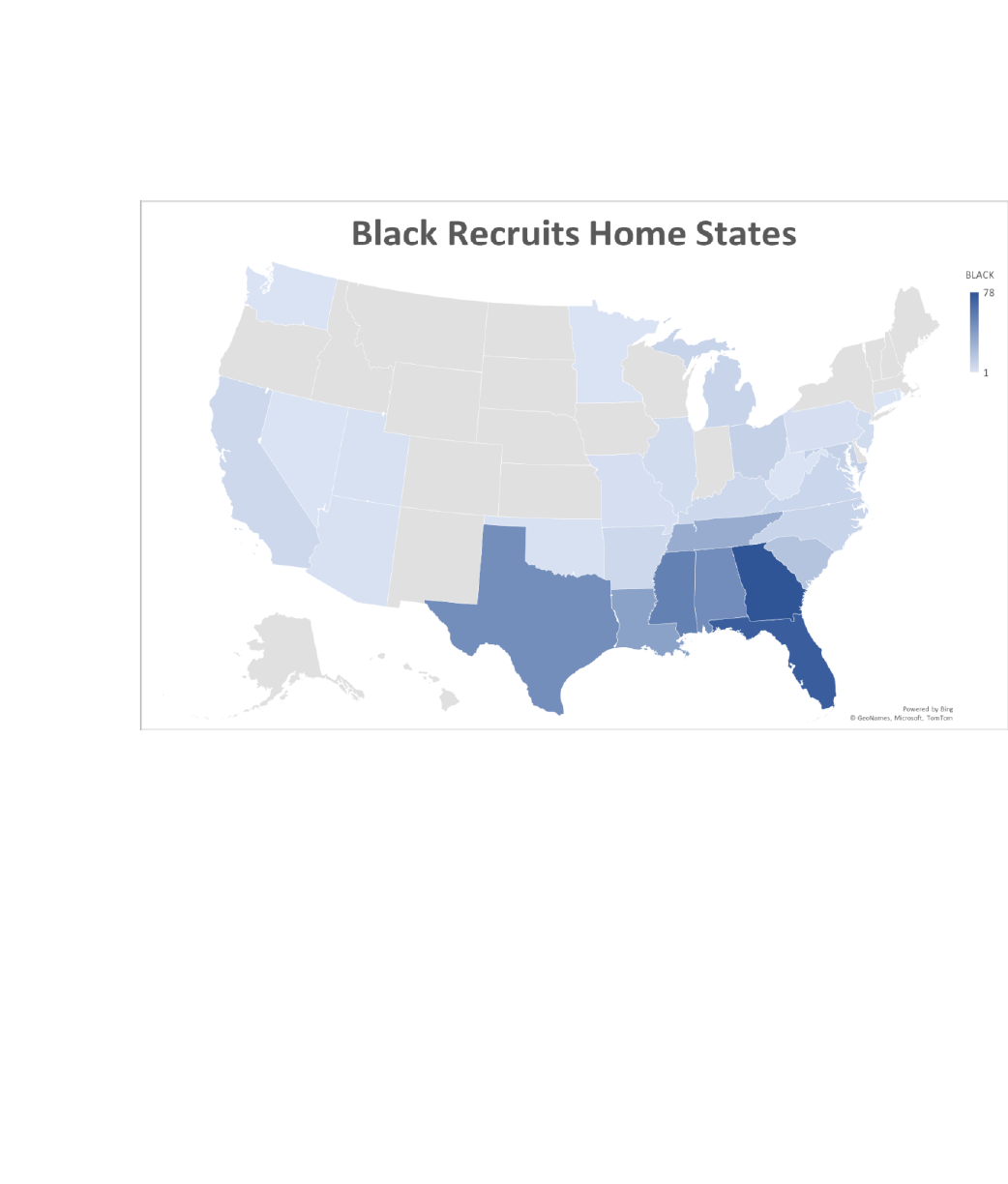

Figure 4.4 Black Recruits Home States ......................................................................... 127

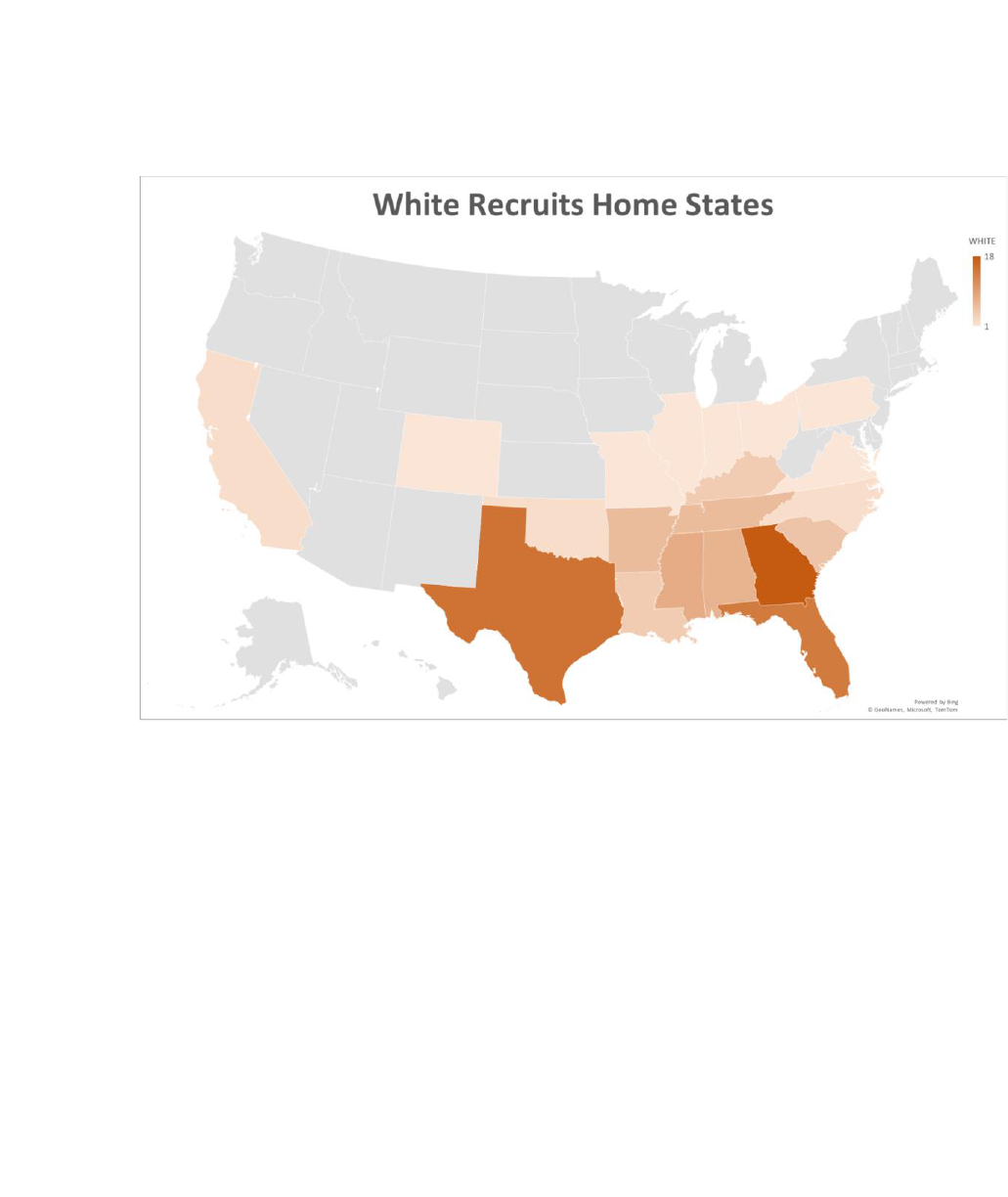

Figure 4.5 White Recruits Home States ......................................................................... 128

xi

LIST OF SYMBOLS

n The total number of observations within a given sample

M Average value of grouped findings.

p Level of significance within statistical test.

xii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AAC ................................................................................... American Athletic Conference

ACC .......................................................................................... Atlantic Coast Conference

ACS ..................................................................................... American Community Survey

AFCA .................................................................. American Football Coaches Association

AGG ........................................................................................... Adjusted Graduation Gap

AP ............................................................................................................. Associated Press

APR .............................................................................................. Academic Progress Rate

Big-10 ................................................................................................. Big Ten Conference

Big XII ................................................................................................. Big XII Conference

CCA .......................................................................... College Commissioners Association

CFP .............................................................................................. College Football Playoff

CRT .................................................................................................... Critical Race Theory

CSRI ................................................................................. College Sport Research Institute

C-USA ...................................................................................................... Conference USA

FBI .................................................................................... Federal Bureau of Investigation

FBS .......................................................................................... Football Bowl Subdivision

FGR .............................................................................................. Federal Graduation Rate

FOIA ...................................................................................... Freedom of Information Act

GA ......................................................................................................... Graduate Assistant

GIA ................................................................................................................. Grant-in-Aid

xiii

GPA .................................................................................................... Grade Point Average

GSR .............................................................................................. Graduation Success Rate

HBCUs ......................................................... Historically Black Colleges and Universities

MAC ........................................................................................ Mid-American Conference

MANOVA ..................................................................... Multivariate Analysis of Variance

MWC ....................................................................................... Mountain West Conference

NCAA ................................................................. National Collegiate Athletic Association

NCSA ................................................................................... Next College Student Athlete

NFL ............................................................................................. National Football League

NLI ................................................................................................ National Letter of Intent

PAC-12 ............................................................................................ Pacific-12 Conference

PSA ......................................................................................... Prospective Student-Athlete

PWI .................................................................................. Predominantly White Institution

SEC ............................................................................................. Southeastern Conference

Sun Belt .............................................................................................. Sun Belt Conference

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

In the fall of 2018, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) made

significant changes to the manner which college athletes can transfer institutions (G.

Johnson, 2019). “The transfer portal” has altered the landscape of college athletics by

removing transfer and eligibility barriers (Dodd, 2019). Nowhere has the effect of the

transfer portal been greater than in Division I football. During the 2018-2019 academic

year, nearly 10,000 college athletes from Division I institutions entered their names in the

transfer portal. Football players accounted for 25% of these transfers (G. Johnson, 2019).

This 25% represents an increase of about 1,000 Division I football players’ intention to

transfer from the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 academic years; the two academic years

prior to the implementation of the transfer portal (NCAA, 2019a). In addition to the

implementation of the transfer portal, the NCAA adopted a one-time transfer exemption

rule in April 2021. Previously, college athletes were prohibited from participating in

athletic competition for one academic year upon transferring (Dellenger, 2021). The one-

time exemption allows college athletes to transfer institutions once without having to sit

out from competition for any amount of time (Auerbach, 2021). Some college football

coaches have likened the transfer portal and transfer exemptions to National Football

League (NFL) free agency where a market is created by multiple teams bidding for the

services of players (Caron, 2019; Costello, 2021; Vrentas, 2021). Whereas in the NFL the

2

market created by free agency can lead to lucrative contracts, in college football the

transfer market bears no financial ramifications on the athlete.

The easing of restrictions on college athlete transfers and recent litigation on

college athlete compensation heard by the United States Supreme Court (Alston v. NCAA,

2020) illustrate the manner in which college sports are changing. While the merits of

simplifying the transfer process and allowing college athletes the freedom to transfer in a

manner consistent with traditional students has been a byproduct of the implementation

of the transfer portal (and remains an important dialogue that requires continued

examination and revision [Dodd, 2018; 2019; Higgins, 2019]), the reasoning behind

football players’ decisions to transfer has received insufficient examination. Traditional

students tend to transfer due to academic reasons (Li, 2010), college athletes tend to

transfer for athletics reasons; primarily, when the expectation before attending an

institution doesn’t meet the experience once enrolled (NCAA, 2016). Given the

disconnect between the experience as a recruit and as a college athlete, an examination of

the elements that comprise the recruiting process is merited.

College athletics recruiting is described by the NCAA as the lifeblood of college

sports (NCAA, n.d., para. 1). Recruiting in college football is a major industry that can

carry multi-million-dollar ramifications for athletic departments and coaches. During the

2017-2018 academic year, 62 college football programs spent over a million dollars on

recruiting alone (Ching, 2018). College football coaches are compelled to make large

financial investments in recruiting due to the effect that successful recruiting can have on

job retention (Maxcy, 2013). Successful recruiting can help save a coach’s job in a

volatile field where 11% of NCAA Division I head football coaches are fired each year

3

(Daughters, 2013). Additionally, college athletic departments make the investment in

football recruiting due to the relationship between recruiting success and team success

(e.g. winning championships) (Caro, 2012; Caro & Benton, 2012). The monetary benefits

that accrue to athletic departments with successful (i.e. winning) football programs make

the investment in football recruiting a worthwhile risk. The University of Alabama for

instance, has seen expenses for the football program rise by over 75% since head coach

Nick Saban’s hiring in 2007 (Casagrande, 2016). In 2019, Alabama football spent $2.6

million on recruiting; up 30% from 2015 (Casagrande, 2020). The investment, however,

has paid off with 9 top-ranked recruiting class and 6 national championships in Saban’s

14-years as head coach. Alabama’s athletic department has seen revenue increase from

$64 million in 2008 to $164 million in 2019 (Casagrande, 2016; 2020).

Alabama’s football team accounted for $106.3 million of the revenue generated

by the athletic department in 2019. Of Alabama’s 18 other athletic teams, men’s

basketball was the only team to make money in that year; generating $66,921

(Casagrande, 2020). Such figures illustrate the dominant institutional logic that major

college athletics operate within. Southall & Nagel (2009) coined the term jock capitalism

to describe the financial enterprise that dictates college athletics under the guise of

amateurism. Profit-athletes are “NCAA college athletes whose estimated market value

exceeds the value of NCAA-approved compensation (i.e. grant-in-aid),” and typically

consist of athletes in the sports of football and men’s basketball (Kidd et al., 2018, p.

116). Profit-athletes are responsible for generating money that in large part funds the

entire athletic department, sustaining the operation of all the other athletic teams

sponsored by the University (Southall & Weiler, 2014). An unconscious adherence to the

4

dominant institutional logic of jock capitalism ensures that those within major college

athletics maintain an unspoken code of silence (Adams et al., 2014; Gutierrez &

McLaren, 2012; LoMonte, 2020) while maintaining that “amateur defines the

participants, not the enterprise” (Brand, 2006, p. 8).

While studies on college athletics recruiting can be found in the literature, other

studies cater towards practice in the areas of recruiting and coach retention (Maxcy,

2013), the relationship between recruiting success and team success (Bergman & Logan,

2016; Caro, 2012; Caro & Benton, 2012; Dronyk-Trosper & Stitzel, 2017; Langelett,

2003; Pitts & Evans, 2016), NCAA regulations and parity between teams (Eckard, 1998;

Fizel & Bennett, 1996), geographic recruiting areas (May, 2012; Reimann, 2004), media

coverage (Yanity & Edmondson, 2011), and the qualities that comprise a successful

recruiter (Magnusen et al., 2011; Magnusen et al., 2014; Treadway et al., 2014). While

not attempting to underscore the importance of conducting research with practical

ramifications, a theoretical examination of the recruiting process from an institutional

standpoint is missing in college athletics recruiting literature.

In college athletics, recruiting informs the decision-making process for which an

athlete will sign a National Letter of Intent (NLI) (Bigsby et al., 2017; Corr, Southall, &

Nagel, 2020; Czekanski & Barnhill, 2015; Dumond et al., 2008). The football recruiting

process creates an expectation as to what life as an athlete will entail and, as evident by

the number of college football players entering the transfer portal, that expectation is not

always indicative of the lived college experience (Corr, Southall, & Nagel, 2020; NCAA,

2016). Utilizing institutional logic as a theoretical starting point, this dissertation aims to

examine the Power-5 college football recruiting process; with specific regards to

5

institutional practices (that create expectations [Corr, Southall, & Nagel, 2020]) and the

role of recruiters performing institutional work. The line of research was, by design,

systematic in that (1) institutional recruiting practices were examined, (2) the recruiters

performing institutional work were examined, and (3) the institutional practices and

recruiters performing institutional work were examined utilizing a critical race

perspective. While the gap in the literature made the research area appealing, the

examination of the recruiting process from an institutional standpoint has potential

significance both theoretically and practically. Currently, such an examination may not

exist due to the difficulty of penetrating the insider-only collective that is college athletics

(Adler & Adler, 1991; Hatteberg, 2018; Southall & Weiler, 2014).

6

CHAPTER 2

SOUTHEASTERN CONFERENCE RECRUITING OFFICIAL VISITS

AND THE MAINTENANCE OF THE INSTITUTION OF POWER-5 COLLEGE

SPORT

While all college athletes, their families, and fans of every college sport are

emotionally invested in “their” sport, the level of scrutiny and financial investment in

recruiting is most pronounced at the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) level,

among what have become known as the “Power-5” and “Group of 5” conferences. The

Power-5 conferences include the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), Big Ten Conference

(Big-10), Big XII Conference (Big XII), Pacific-12 Conference (PAC-12), and

Southeastern Conference (SEC). The Group of 5 conferences include the American

Athletic Conference (AAC), Conference USA (C-USA), Mid-American Conference

(MAC), Mountain West Conference (MWC), and Sun Belt Conference (Sun Belt).

The apex of college-sport recruiting takes place within Power-5 athletic

departments that have budgets that routinely exceed $100 million. Table 2.1 highlights

the ten Power-5 athletic departments with the highest revenues and expenses. Within the

Power-5 institutional field, football and men’s basketball are the sports that provide

almost all athletic department revenues. Much of the revenues are dispersed to athletic

departments from Power-5 conference media rights (See Table 2.2).

There are numerous recruiting websites that produce recruiting news 24-hours a

day, 7-days a week. Sports and entertainment networks (e.g., ESPN, NBCSN, and Fox

7

Sports) devote hours of programming prior to the various “National Signing Days.” Two

prominent recruiting websites include the “official” National Letter of Intent

(nationalletter.org), jointly administered by the Collegiate Commissioners Association

(CCA) and the NCAA and Next College Student Athlete (NCSA)

(https://www.ncsasports.org), formerly known as the National Collegiate Scouting

Association.

Recruiting and signing college athletes is so important that within hours of

winning the 2015-16 College Football Playoff (CFP) national championship, Smith

(2016) noted University of Alabama head football coach Nick Saban was busy contacting

recruits hoping to secure commitments. Coaches, players and fans recognize the

importance of recruiting, particularly among the Power-5 sports of football, and men’s

and women’s basketball. Future players, as young as 14-years of age, are already on fans’

proverbial radar screens. Head and assistant coaches know full well their livelihood

depends on successful recruiting (Wood, 2010). In some cases, college coaches are

scorned for recruiting failures as much as on-the-field-or-court subpar performances.

Athletic directors and college presidents often field questions from fans and members of

the media concerning their coaches’ recruiting efforts. In today’s social media

environment, fans react to recruits’ posts as real-time indicators of coaches’ recruiting

proficiency or deficiency. Increased year-round attention has resulted in a limited amount

of “down time” for everyone involved.

In response, in 2004 the NCAA instituted restrictions on campus visits to, “…end

the celebrity atmosphere that [had] developed around the recruiting visit” (Hutton, 2004,

para. 5). Despite the heightened focus on college sport recruiting and its importance in a

8

program’s success, little is known about the recruiting process beyond anecdotal accounts

and portrayals in movies and television shows (Bennett, 2008). Guided by organizational

and institutional theories, this study examines the content of Power-5 conference official

visit itineraries and compares findings by gender and sport.

Theoretical Frameworks

Organizational Culture

NCAA teams, athletic departments, and Power-5 conferences all have an internal

set of agreed upon values, which at an individual organizational level Schein (1984)

identified as an organization’s culture: basic assumptions that have been invented,

discussed or developed to address problems or challenges. After these assumptions have

worked well enough to be considered valid, they are taught to new members as “…the

correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems” (Schein, 1984, p. 3).

These symbolic organizational assumptions and structures rationalize an organization’s

stated values and guide organizational members’ practical day-to-day actions. Since

values are aspirational, organizations must also develop and pass on to new members

cultural templates as guardrails that have worked in the past, and can be relied upon by

members as they face present-day challenges.

At Power-5 team, athletic department, and conference levels, there is an interface

in which dominant individual organizational cultures coalesce into an overarching

dominant institutional logic, which – in the case of NCAA Power-5 college sport –

Southall and Nagel (2009) referred to as “jock capitalism.” This institutional structure,

which provides stability and meaning (See Figure 2.1), did not develop organically but

was created – and has been subsequently maintained and supported – through the shared

9

efforts and choices of Power-5 team, athletic department and Power-5 conference

members. This organizational/institutional structure is not monolithic and homogenous

but rather an arrangement in which constant tension exists and negotiation occurs among

and between organizational and institutional members.

Institutional Theory

In addition to research utilizing an organizational culture framework, various

elements of institutional theory, including: institutionalization, institutional logics,

institutional change, and institutional propaganda have been used to examine the macro-

dynamics through which large-scale social and economic changes have occurred within

the Power-5 college-sport institutional field (Southall & Staurowsky, 2013). Fundamental

to any of these processes is a system of institutional values and practices that are

“…taken for granted presumably because people are either not consciously aware of,

perceive, or question these phenomena” (Woolf et al., 2016, p. 439). As Jepperson (1991)

and Woolf et al. (2016) noted, these represented institutional practices are similar to

performance scripts that institutional members perform almost without thinking. These

scripts not only determine acceptable or unacceptable operational means, they also guide

the implementation of institutional strategies, routines, and precedents (Southall et al.,

2008).

As Meyer and Rowan (1977) discussed, in order to maintain the ceremonial

conformity of policies and practices that function as powerful myths and are

institutionalized as rationalized concepts of organizational work, organizations adopt

formal structures that reflect “…the myths of their institutional environments instead of

the demands of their work activities” (p. 341). These mythological institutional rules tend

10

to buffer formal structures from the uncertainties that arise between formal structures and

actual work activities (Meyer & Rowan, 1977).

During official visits, which can last no longer than 48-hours, institutions can pay

for a prospect’s (and up to four family members) transportation to and from campus,

lodging, meals, and entertainment (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.4). Throughout the

recruiting process, recruiters perform institutional work, through which they articulate to

recruits purported institutional structures within which the recruits will live, work and

play once they have been accepted as members of the athletic team. Official visits are

presented to recruits as an indication of the lived experiences of current team members.

Throughout scripted official visits, recruiters communicate mythological ceremonial

facades to recruits.

As Scott (2005) noted, the myriad facets of institutional theory provide a context

within which to investigate an institutional field. Institutional actors operate within these

“rationalized” systems in pursuit of specified goals. In addition, these models of

rationality are cultural systems “…constructed to represent appropriate methods for

pursuing [institutional goals] or purposes” (Scott, 2005, p. 5). Consistently, institutional

theorists (e.g., Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Nite et al., 2019; Nite & Washington, 2017; Scott,

2005, Southall et al., 2008) have posited that an institution’s norms of rationality play a

causal role in the creation and maintenance of formal organizational structures and

accepted, taken-for-granted facts, which Friedland and Alford (1991) identified as a

central or dominant institutional logic. On a macro level, this logic not only guides the

development, evaluation and implementation of strategies, but also informs operational

procedures and future innovation (Duncan & Brummett, 1991; Friedland & Alford, 1991;

11

Nelson & Winter, 1982; Washington & Ventresca, 2004). An institution’s dominant logic

shapes how institutional actors engage in coherent, well-understood, and acceptable

activities. In this sense, then, institutions become “encoded in actors’ stocks of practical

knowledge [that] influence[s] how people communicate, enact power, and determine

what behaviors to sanction and reward” (Barley & Tolbert, 1997, p. 98). However, these

unquestioned facts (e.g., an institution’s logic) may be subject to ongoing dissonance, or

– over time – the institutional field may be disrupted.

Dominant Power-5 Institutional Logic

The dissonance between higher education’s espoused educational values and

those of

Division I (e.g., Power-5) college athletic departments has been well documented. As far

back as 1929 the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching contended

college sport was being ruined by commercialism and detailed abuses that threatened to

corrupt college sport`s presumed purpose (Hersch, 1990). For almost as long as college

sport has existed, a common criticism has been college and universities have sacrificed

their academic credibility in the name of athletic success (Hersch, 1990). This value

incongruence, as Schroeder (2010) noted, is the result of an institutional field in which

athletic departments are – in many ways – independent institutional entities that often

develop independent values that are in conflict with those of the universities in which

they are housed.

However, college athletic departments are not monolithic organizations with only

one set of departmental values or practices. In addition, the institution of NCAA Power-5

college sport is not homogeneous. Numerous investigations (Padilla & Baumer, 1994;

12

Putler & Wolfe, 1999; Santomier et al., 1980; Schroeder, 2010; Southall et al., 2005)

have found competing athletic department priorities, with Southall et al. (2005) and

Schroeder (2010) uncovering significant differences between the most crystalized values

of Division I and Power-5 revenue and non-revenue, and male and female sport

programs, with the most pronounced differences being between football and men’s

basketball and all other sports. Within FBS Power-5 Conference athletic departments,

male revenue-sports constitute a subculture that values winning above almost anything

else and feels constrained by many NCAA bylaws (Santomier et al., 1980; Southall et al.,

2005). Tellingly, Martin (1992) noted members who feel disconnected from espoused

core organizational values either develop a counterculture and engage in organizational

deviance or adopt a competing institutional logic that replaces the previously dominant

one.

In 1987, Sack developed a college-sport matrix that delineated the various levels

of professionalism and commercialism that exist in the institutional field of NCAA

college sport. He contended that college sport was to varying degrees both professional

and amateur, as well as commercialized and non-commercialized. The various NCAA

divisions and conferences epitomized these differentiations (See Figure 2.2). Within this

identified institutional field, there is strong evidence that over the past 50 years a

commercialized, revenue-seeking institutional logic has become dominant within Power-

5 college sport (Southall & Nagel, 2008; Southall et al., 2008; Southall, Southall, &

Dwyer, 2009; Southall et al., 2014).

13

Institutional Work

The creation, maintenance and disruption of an institution’s dominant logic does

not occur in isolation but is the result of – and reflects – the lived experiences of

organizational and institutional actors. Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca (2011) describe this

process as institutional work, which occurs within existing institutional structures, while

simultaneously producing, reproducing, and transforming the institution. Institutional

work offers a framework within which institutional actors live, work, and play, and which

delineates their roles, relationships, resources, and routines (Lawrence et al., 2011).

The concept of institutional work moves beyond the static view that embedded

institutional norms, structures and logics reproduce regardless of praxis (DiMaggio &

Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977) and recognizes that influential institutional leaders

often actively create, maintain, disrupt and recreate institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby,

2006; Nite & Washington, 2017).

An example of a leader’s institutional disruption and recreation of an institution’s

logic through the introduction, dissemination, and insertion of a performance script into

an institution’s consciousness was Myles Brand’s (former NCAA President) institutional

work redefining amateurism as The Collegiate Model of Athletics, which isolated the

concept of amateurism to college athletes while allowing rampant commercialism and

maximization of revenue-producing opportunities (NCAA, 2010). As Southall &

Staurowsky (2013) noted, Brand wanted to maintain the collegiate model by engaging in

institutional work that legitimized college athletes’ exclusion from college sport’s jock

capitalism.

14

Almost 10-years later, this institutional script (i.e., the collegiate model) has

gained so much traction within the institutional field of NCAA Power-5 college sport that

on October 29, 2019, when the NCAA national office disseminated a press release

outlining a “ground-breaking” shift in policy toward players’ use of their own name,

image and likeness, the collegiate-model institutional script was utilized as a delimiting

maintenance tool. The press release positioned the NCAA as supporting college athletes’

rights and embracing “…change to provide the best possible experience for college

athletes” (NCAA, 2019c, para. 1). However, the release’s lede still articulated a

commercial institutional logic that restricted college athletes’ right to benefit from the use

of their name, image and likeness, since any monetization had to occur within the

NCAA’s collegiate model (NCAA, 2019c, para. 1). What is left unsaid is that the

collegiate model (as embodied in NCAA bylaws) precludes college athletes from

receiving: “Any direct or indirect salary, gratuity or comparable compensation” (NCAA,

2019d, Bylaw 12.1.2.1.1.). The use of this script is consistent with the theory of

institutional work, since institutional actors who benefit from an institutional script tend

to work to maintain their favorable positions (Nite & Washington, 2017).

Within NCAA Power-5 college sport (football and men's basketball in particular)

recruiting is impacted by technical forces that shape the “core” functions (e.g., work

units, coordinated arrangements and duties of recruiters), as well as institutional forces

that reflect more peripheral structures (e.g., managerial and governance systems imposed

by the NCAA governance structure) (Scott, 2005). Within Power-5 college sport

recruiting, some institutional requirements (e.g., NCAA recruiting-related bylaws) are

strongly backed by authoritative agents or effective surveillance systems and sanctions

15

(e.g., NCAA, conference, and/or athletic department compliance offices). Recruiters’

responses to such forces will vary, depending on which elements are predominant:

external controls (e.g., surveillance and sanctions) or internalized processes that rely on

organizational actors holding deeply set beliefs and assumptions (Scott, 2005). External

controls – in the absence of deeply set beliefs – often result in strategic deviant responses

(e.g., bending, breaking or ignoring imposed rules) (Santomier et al., 1980; Southall et

al., 2005).

This exploratory study drew upon institutional theory and, specifically,

institutional work to examine official recruiting visits as examples of institutional

maintenance work, since although institutions are considered to be enduring entities,

organizational actors must still “work” to maintain and communicate institutional

practices to internal and external constituencies. Specifically, if one of a college-sport

recruiter’s tasks is communicating a team’s values to recruits, an official visit

communicates to prospective members how institutional members communicate, enact

power, and determine what behaviors will be sanctioned or rewarded (Barley & Tolbert,

1997). An official visit’s unquestioned, taken-for-granted “facts” reflect particular

courses of action developed into performance scripts (i.e., official visit itineraries), which

introduce recruits to a team’s institutional practices (Jepperson, 1991; Lawrence &

Suddaby, 2006; Woolf, et al., 2016).

An important element of an official recruiting visit is determining whether recruits

“fit in.” Consistent with Woolf et al. (2016), one of a recruiter’s major functions is

developing a structure within which recruits are socialized into existing institutional

16

practices. The maintenance of existent institutional norms depends on recruits being

exposed to and coming to embrace and internalize a team’s espoused values .

Research Context

In official NCAA parlance, recruiting is “…any solicitation of a prospective

student-athlete

1

(PSA) or a PSA’s relatives…by an institutional staff member or by a

representative of the institution’s athletics interests for the purpose of securing the PSA’s

enrollment and ultimate participation in the institution’s intercollegiate athletics

program” (NCAA, 2019b Bylaw 13.02.14). While a football or men’s basketball

program’s success (e.g., wins, players “turning pro”) is a key factor in many player

decisions, visiting campus is an important opportunity for a program to sell itself, and

players to find out if they are comfortable with the coaches and other players (Anderson,

2012; Lawrence & Kaburakis, 2008; Letawsky et al., 2003). Power-5 prospects may take

five official visits during their senior year but can take no more than one to any individual

institution (NCAA, 2019b Bylaw 13.6.2.1; Bylaw 13.6.2.2.1.3).

2

Broadly, Bylaw 13 of the NCAA D-I Manual outlines recruiting guidelines. There

are specific policies related to transportation (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.5), lodging

(NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.6), entertainment (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.7),

complimentary admissions to athletic events (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.7.2), meals

(NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.7.7), and cash disbursement to student host(s) to cover costs

1

Consistent with Staurowsky and Sack (2005), in this manuscript the term “student-

athlete” refers to a specific use in an NCAA bylaw (e.g., “prospective student-athlete”).

In all other circumstances, the term “college-athlete” is used.

2

Football recruits may begin taking official visits April 1

st

of their junior year. Men’s

basketball recruits may take five official visits during their junior year and an additional

five during their senior year.

17

for entertainment (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.7.5) while PSA’s and their family are on

an official visit. Other than the NCAA Eligibility Center clearing a PSA to take an

official visit, there are no bylaws specifically mandating academic-related discussions

during an official visit.

Given an official visit’s importance and relatively short (48-hour) duration,

planning is extremely detailed, with time often allocated down to the minute (Sallee,

2014). In most instances, programs prepare a written itinerary and provide it to a recruit’s

travel party and current athlete host(s). According to the NCAA’s regulatory framework,

official-visit activities must be comparable to what a “regular student” might experience

on a campus visit, or at least commensurate with what is regularly provided to athletes at

that institution (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaws 13.6.6; 13.6.7.7). In addition, the NCAA wants

official visits to mimic what a college athlete should expect upon enrollment at an

institution. Extant research has found campus visits aid in prospective students’

understanding of “the nature of college…[which] may be important to his or her future

success…[and being] academically [prepared] for college admission” (Radcliffe & Bos,

2013, p. 137). Lytle (2012) notes college campus visits are intended to provide

prospective college students with brief – but realistic – introductions to campus life,

which will assist in students’ college-selection process.

Another purpose of any college visit is to introduce prospective students to the

concept of time management. It is customary for a full-time college student to be enrolled

in four-to-five courses, which meet for 12-15 hours per week (Pelletier & Laska, 2012).

In addition, it is recommended college students devote two-three hours per week to

outside study time for each hour of class time (Nelson, 2010). This equates to 30-45

18

hours per week for a full-time student enrolled in four-to-five classes. The NCAA (2016)

contends college athletes spend 38.5 hours (23% of their week) on academics. According

to the same NCAA report, college athletes spend an average of 34 hours (20%) on

athletics (NCAA, 2016).

For traditional prospective SEC students (i.e., students not participating in

collegiate athletics), campus tours are standardized across the 14-member conference.

Each SEC university has an admissions page where students can register for a campus

tour. While the campus tour is complementary, expenses related to travel, lodging,

dining, and even parking are the responsibility of individual potential students and their

family. According to admissions office websites, these campus tours usually last 2-4

hours and consist of an academic information session, and tours of the central part of

campus, libraries, dorm rooms/student housing, dining halls/food courts, and recreation

facilities. In addition, many individual colleges and departments within SEC universities

also offer orientations for admitted students that function as an extension of the university

campus visit. These orientations, while specialized to a specific academic discipline, do

not include reimbursement for travel, lodging, dining, or parking.

Within this context, this study documented and categorized official-visit

itineraries as examples of institutional work performed by members of SEC teams and

athletic departments. The following section details the sampling frame, as well as the

data-collection and coding procedures.

19

Methodology

Sampling Frame

The Southeastern Conference (SEC) was chosen as this study’s sampling frame

due to the conference’s position as the premier conference in collegiate athletics (Renkel,

2017). The SEC consists of 14 member institutions and offers a total of 21 sports: 9

men’s and 12 women’s. While offering the least number of sports among Power-5

conferences, the SEC spends more money on recruiting than any other conference

(Ching, 2018). In terms of a financial commitment, the SEC places more of an emphasis

on recruiting than any other Power-5 conference. Notably, in 2017-2018, SEC athletic

departments had four of the top-five and eight of the top-20 Power-5 recruiting budgets

(Ching, 2018).

Procedure

Emails were sent to a designated member of each varsity sport

coaching/recruiting staff within each SEC athletic department, requesting official visit

itineraries from the year 2018 or 2019. For each institution and team, at least three

attempts were made. No responses or acknowledgments of these initial communication

attempts (across any sport or program) occurred. After achieving no success in obtaining

information via email solicitations, acquiring data through Freedom of Information Act

(FOIA) requests was deemed the most efficient strategy, since 13 out of the 14 SEC

member universities are public universities (Vanderbilt University is the only private

university). Eight athletic departments responded to the FOIA request by providing

standard official visit itineraries across multiple sports from 2018 or 2019. Two athletic

departments requested payment to complete the FOIA request and three athletic

20

departments provided no response. It should be noted that the three athletic departments

that did not respond operate in states that require residency requirements to fulfill FOIA

requests.

Data

A “typical” itinerary consisted of one-to-two pages of chronologically-organized

activities with parenthetical location and transportation information. All itineraries

presented a detailed schedule outlining official-visit activities. Contact information for

coaches, support staff, and athlete hosts was also noted on itineraries.

Within a thematic framework containing three college-athlete roles: 1) athletic, 2)

academic, and 3) social (Adler & Adler, 1987; 1991), official-visit itinerary elements

were coded and duration of activities (in minutes) calculated. The NCAA classification of

recruits as “prospective student-athletes,” purportedly acknowledges the primacy of

recruits’ academic role. In addition, acknowledging the importance of allowing recruits to

socialize and be entertained NCAA regulations: a) permit travel of up to 30 miles from an

institution’s primary campus for the purpose of entertainment while a PSA is on an

official visit (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.7.1); b) allow institutions to spend up to $40

per day, per PSA on activities specifically related to entertainment (NCAA, 2019b,

Bylaw 13.6.7.8); and c) permit a student host, or a member of an athletic team at the

institution, to be provided with $40 per day for the purpose of entertaining a PSA during

an official visit (NCAA, 2019b, Bylaw 13.6.7.5).

Individual activities were coded by a team of researchers trained in thematic and

discourse analysis. An athletic activity was any activity specifically related to potential

sport participation (i.e., meeting with an athletic coach, observing practice or an athletic

21

contest, trying on athletic equipment, and/or taking a tour of a strength and conditioning

facility). An academic activity was specifically related to academics (i.e., meeting with a

faculty member, observing a college class, and/or taking a tour of an academic facility).

Examples of social activities were going to the movies with a host(s), attending a football

game

3

, and/or sharing a meal with current team members. It should be noted that across

all sports, social activities almost exclusively took place in the evening or at night. Table

2.3 provides representative coding examples.

The number of times a themed-activity was listed, as well as the amount of time

dedicated to that activity during a 48-hour official visit was calculated. By summarizing

listed instances and minutes dedicated , the amount of institutional work devoted to each

theme/role could be determined. The twenty-one individual sports were initially

categorized by gender. In addition, based on Sack’s (1987) and Southall and

Staurowsky’s (2013) typologies, sports were separated into three categories related to

revenue generation: a) non-revenue sports, b) revenue sports, and c) profit sports. The

non-revenue sports in this study typically generate less than $100,000 of revenue and

included: beach volleyball, equestrian, men’s and women’s golf, gymnastics, lacrosse,

rifle, soccer, softball, men’s and women’s swimming & diving, men’s and women’s

tennis, men’s and women’s track & field, volleyball, and wrestling. Revenue sports were

baseball and women’s basketball, teams that may generate substantial revenue but still

have expenses that exceed revenues. Power-5 profit sports are football and men’s

3

For non-football PSA’s, attending a football game was coded as a “social” activity.

However, a football PSA attending a football game was coded as an “athletic” activity,

since a football player would not view the game as a social event but as an athletic event.

Therefore, when PSAs attended a sporting event in which they would participate as a

college athlete, attending that game was coded as an athletic activity.

22

basketball, teams that generate more revenue than expenses and fund revenue and non-

revenue sports’ operations. For some analyses, MANOVA tests compared variables

across a sample of eight institutions, allowed inferences across the 14 SEC members.

Findings

In total, 76 official visit itineraries from 21 sports from 2018 or 2019 were

collected. Thirty-three itineraries (43%) were from men’s sports and 43 (57%) were from

women’s sports. All itineraries allotted eight-hours each night for sleeping. Sixty-seven

of 76 (88%) itineraries listed the official visit’s date/day. Fifty-two (78%) official visits

took place over the course of a weekend (Friday through Sunday). Baseball (n = 4),

football (n = 7), and gymnastics (n = 4) were the only sports to have, exclusively,

weekend official visits.

Only 17 of 75

4

(23%) recruits stayed in dormitories with current college athletes

during their official visit. Of the 17 who stayed in dormitories, all were from non-revenue

sports: (i.e., equestrian, women's golf, gymnastics, rifle, softball, men's swimming &

diving, women's swimming & diving, women's tennis, women’s volleyball, and

wrestling), and only three were male athletes (2 swimming & diving, 1 wrestling). Fifty-

seven of 75 recruits (76%) stayed in a hotel during their official visit. While 12 itineraries

did not specifically name the hotel, 45 recruits stayed at an identified hotel. According to

Google’s hotel “class-rating” measure (recognized by Forbes as a leading hotel review

site [Elliott, 2018]), 14 recruits (31%) stayed at a 4-star hotel

5

, 25 recruits (56%) stayed

4

One women’s volleyball itinerary did not report where PSA stayed during the official

visit.

5

Baseball, men’s basketball (2), women’s basketball, football (3), gymnastics, soccer,

men’s tennis, men’s track & field, women’s track & field (3).

23

in a 3-star hotel

6

, and six recruits (13%) stayed in a 2-star hotel

7

. It should be noted that

within individual athletic departments, many teams utilized the same hotel for official

visits. Of the 14 recruits who stayed at a 4-star hotel, eight were recruits of the same

school and represented six different sports.

8

Overall, recruits tended to stay at the highest

rated hotel in closest proximity to campus.

Overall, social activities were the most prevalent (M

Social

= 8.2) and had the most

time allocated (M

Social

= 10 hours and 35 minutes [10:35]). Athletic activities (M

Athletics

=

4.1) were less prevalent and had less time allotted (M

Athletics

= 4:58). Academic activities

were the least prevalent (M

Academics

=1.2) (M

Academics

= 1:06).

Individual Sports

Table 2.4 summarizes itinerary content by sport. When individual sports were

examined, several noteworthy findings emerge.

Gymnastics (M

Social

= 14:35), football (M

Social

= 14:23), and men’s swimming &

diving (M

Social

= 13:20) dedicated the most time to social activities, while rifle (M

Social

=

5:30), women’s volleyball (M

Social

= 5:00), and women’s lacrosse (M

Social

= 4:25)

dedicated the least. Rifle (M

Athletics

= 11:00), women’s swimming & diving (M

Athletics

=

7:09), and men’s basketball (M

Athletics

= 7:06) dedicated the most time to athletics, while

softball (M

Athletics

= 3:08), women’s golf (M

Athletics

= 2:26), and women’s lacrosse (M

Athletics

= 0:00) dedicated the least. Equestrian (M

Academics

= 6:35), rifle (M

Academics

= 6:30), and

6

Baseball, women’s basketball (2), football (2), men’s golf, women’s golf (2),

gymnastics, lacrosse, soccer (2), softball (3), men’s swimming & diving, women’s

swimming & diving (2), men’s tennis, women’s tennis (2), men’s track & field (3),

women’s track & field.

7

Baseball, men’s golf (2), soccer, men’s track & field, volleyball.

8

Baseball, football, soccer, men’s tennis, men’s and women’s track & field.

24

women’s lacrosse (M

Academics

= 2:15) dedicated the most time to academics but each sport

had only a single itinerary. The gender-combined sports (i.e., women’s [M

Academics

= 2:03]

and men’s track & field [M

Academics

= 2:00]; women’s [M

Academics

= 1:24] and men’s

swimming & diving [M

Academics

= 1:26]) dedicated the most time to academics, while

women’s volleyball (M

Academics

= :15), baseball (M

Academics

= :15), and women’s soccer

(M

Academics

= :24) dedicated the least.

Gender

Table 2.5 highlights the gathered data in the context of gender differentiations.

While men’s sports dedicated 1:42 more time to social activities, time dedicated to

athletics was roughly equivalent for men’s (M

Athletics

= 4:57) and women’s (M

Athletics

=

4:59) sports. However, the number of athletic activities was greater in men’s (M

Athletics

=

4.7) than women’s sports (M

Athletics

= 3.7). Men’s and women’s itineraries contained

roughly the same number of academic activities (M

Academics

= 1.1 and 1.2) but women’s

sports dedicated 24 minutes more to academics. In addition, multivariate analyses for

gender indicated that official visits for male sports dedicated significantly less time to

academics than official visits for female sports (P<.01).

Non-Revenue Sports

The average amount of time devoted to social activities during non-revenue sport

visits was (M

Social

= 10:23). The average number of athletic activities among non-revenue

sports was (M

Athletics

= 3.8), spanning (M

Athletics

= 5:02). The average number of athletic

and academic activities, as well as time allotted to athletic and academic activities, was

nearly identical for male and female non-revenue sports. However, on average, male non-

revenue sports dedicated more time (M

Social

= 1:18) to social activities than female non-

25

revenue sports. The average number of academic activities was (M

Academics

= 1.2), with

only 1:16 during an official visit devoted to academics.

Revenue Sports

Revenue sport (baseball [n = 5] and women’s basketball [n = 3]) itineraries

contained an average of 8.3 social activities with (on average) 10:55 dedicated to social

activities. The average number (M

Athletics)

= 4.0) and time (M

Athletics

= 4:17) of revenue-

sport athletic activities was lower than both non-revenue and profit sports. Across all

groups, academic activities were the least emphasized among revenue sports in both

number of activities (M

Academics

= 0.8) and time (M

Academics

= 0:28). Multivariate analyses

for sport groupings indicated that revenue sports dedicated significantly less time to

academics than non-revenue sports (P<.05).

Profit Sports

Football (n = 7) and men’s basketball (n = 4) itineraries contained an average of

10.1 social activities that comprised 12:10 of a visit. Profit sports dedicated (M

Social

=

1:49) more to social activities than revenue or non-revenue sports, and averaged 2.1 more

athletics activities and dedicated :10 more to athletics. While football and men’s

basketball averaged more academic activities (M

Academics

= 1.4), they dedicated (M

Academics

= :29) less time to academics. Multivariate analyses for sport groupings indicated football

and men’s basketball (i.e., “profit” sports) itineraries involved significantly more social

(P<.075) and athletic (P<.01) activities than revenue sports and non-revenue sports.

Discussion

Within the Southeastern Conference, official visit itineraries function as

performance scripts, in which athletic departments’ institutional practices are performed

26

and conveyed to PSAs. In addition, for recruiters and relevant stakeholders, Power-5

institutional scripts establish routines, communicate acceptable or unacceptable levels of

operational resource allocation and create precedent for changes to strategic initiatives.

While there is evidence of a dominant institutional recruiting logic in the SEC, within

athletic departments profit-sport official visit itineraries are similar in both content and

emphasis, while also significantly different from revenue and non-revenue sport

itineraries. These findings are not surprising, given that the SEC has been described as a

“copy-cat” conference, in which each program (e.g., team and athletic department) is well

aware of what other programs are doing. Teams within each category (i.e., male/female,

non-revenue/revenue/profit) replicated official visit itineraries, which offers evidence of

shared institutional work within the Southeastern Conference.

Consistent with previous research (Southall et al., 2005; Schroeder, 2010), while

there were no significant differences between itineraries based upon athletic department,

this study did find significant differences between profit and non-revenue sport

itineraries. Clearly, this study’s findings offer evidence of subcultures within athletic

departments, as well as the existence of a dominant institutional logic that recognizes the

ascendancy of Power-5 football (and to a lesser extent men’s basketball) within the

institutional field of NCAA Power-5 college sport.

This conference-level dominant logic is not surprising, since less-successful

departments and teams likely model their strategies and performance scripts after those of

more successful (in terms of wins and losses) programs. Given that many SEC coaches

have coached at other SEC schools (Levine, 2015), such mimicry or groupthink is to be

expected. In 2015, following their third national championship in five seasons, University

27

of Alabama football staff complained other football programs were copying many of their

recruiting materials (Kingsbury, 2015). This study’s findings offer evidence recruiters

follow similar “game plans” and engage in similar institutional work (Johnson, 2018).

Within the SEC institutional field, official visits introduce recruits to athletic

departments’ organizational values and the overall institutional practices of SEC

members. Activities undertaken during official visits send subtle and not-so-subtle

messages about what is important to both recruiters and recruits. Tailoring official visits

to what recruits’ value sends distinct signals that may be counter to espoused university

narratives (e.g., The importance of educational opportunities.). According to the Director

of On-Campus Recruiting for a football program in the SEC, a majority of official visits

begin on Fridays, since college football games are, traditionally, held on Saturdays. One

of the most important activities for all recruits (but especially for football recruits) is an

SEC football game (SEC Source 1, personal communication, September 18, 2019).

In addition to SEC football games being almost exclusively Saturday events,

many SEC sports feature competitions that occur over the course of a weekend (e.g., SEC

baseball and softball series typically occur on Fridays, Saturdays, & Sundays and

gymnastics meets are often held on Friday nights). Given these parameters, it is

reasonable that non-revenue recruiting staffs would schedule official visits to coincide

with home football games. According to an SEC football director of player personnel,

while there is some flexibility (based off individual recruits’ requests), official visits tend

to follow a football-centric schedule (SEC Source 2, personal communication, September

19, 2019).

28

Recruits tend to not determine on which specific days an official visit will take

place. In addition, official visits most often take place on weekends, so recruits miss as

little school as possible. However, departments also strategically schedule official visits

on weekends, so recruits can experience an SEC gameday environment. Saturday nights

are tailor-made opportunities for current athletes to socialize with recruits, creating an

expectation of a college athlete’s social life. If official visits began in the middle of the

week (e.g., Wednesday/Thursday), recruits would be exposed to a much different college

experience with a balance of academic/social/athletic activities. While athletic and social

official visit activities are important, weekend recruiting trips limit a recruit’s exposure to

academic activities (e.g., classes, labs, lectures, libraries) and the academic rigors of

college life.

Official visits are formal institutional structures that re-present, as Meyer and

Rowan (1977) stated, “...the myths of their institutional environments instead of the

demands of their work activities” (p. 341). Power-5 official visits present a mythological

portrait of big-time college sport, suppressing and minimizing the academic demands of

attending what is – many times – a rigorous academic institution.

During a weekend official visit, recruits experience a campus environment

markedly different from a mid-week one. In many ways, official visits are ceremonial

façades through which recruiters present a scripted mythological college experience

communicating to recruits the importance of social and athletic activities. However, this

scripted experience bears little resemblance to the reality of college. While “academics”

forms the foundation of the NCAA grant-in-aid system official visits minimize academics

while emphasizing social and athletics activities over academics.

29

Consistent with previous research regarding identified subcultures within Power-5

athletic departments, this study identified competing athletic department priorities

(Padilla & Baumer, 1994; Putler & Wolfe, 1999; Santomier et al., 1980; Schroeder, 2010;

Southall et al., 2005). While – in order to satisfy NCAA recruiting mandates – all sports

adhere to a similar official visit script template, observable differences offer evidence of

subcultures within athletic departments. Specifically, revenue and profit sports dedicated

more activities to social activities than any other component. In addition, profit sports

clearly emphasized athletic and social components, while minimizing academics. While

existence is not causation, such minimization is problematic given that Power-5 football

and men’s basketball players graduate at significantly lower rates than full-time male

students (Southall et al., 2015), consume alcohol at higher rates than both the general

student body and female athletes (Leichliter et al., 1998; Olthuis et al., 2011), and

become engulfed in their glorified athlete role (Adler & Adler, 1987, 1989, 1991; Kidd et

al., 2018). Clearly, this study’s itineraries are not consistent with the totality of a college

athlete’s experience. Identifying this emphasis on athletic and social components during

official visits should inform future research into the relationship of institutional work

(i.e., recruiting) to athletic role engulfment of both Power-5 profit athletes and recruiters.

One of the purported tasks of a college recruiter is communicating institutional and

departmental values, and appropriate and/or acceptable actions and behaviors to recruits.

However, a recruiter’s ultimate goal is getting a recruit to sign a NLI and grant-in-aid

agreement. Therefore, the emphasis placed on specific components of an official visit

reflect the actions Power-5 recruiters deem appropriate to achieve these goals.

30

A variety of future studies should be conducted in this area. Itineraries in other

Power-5 and Group of 5 conferences should be analyzed to determine the extent to which

there is an institutional recruiting logic that permeates Power-5 sports and Power-5 profit

sports in particular. In addition to content analyses, recruits across a variety of sports

should be interviewed to determine specific activities that occurred during their official

visits. To determine the degree to which Power-5 recruiters’ institutional work is

consciously designed to reinforce and support recruits’ athletic role engulfment, it is

suggested in-depth semi-structured interviews with Power-5 sport recruiters also be

undertaken. While such interviews will likely be difficult to arrange, such candid

discussions are a necessary adjunct to this study.

As Power-5 college athletes continue to be engulfed in their athletic roles (Kidd et

al., 2018), the institutional work of recruiting college athletes reflects the production,

reproduction and support for a dominant SEC institutional logic, in which SEC football is

the focal point. As Lawrence (2011) noted, institutional workers continually and actively

determine and transform the institutional structures within which they live, work, and

play. The focus of SEC recruiters on constructing and facilitating athletic and social

activities during official visits communicates to recruits the pre-eminent importance of

their athletic and social roles. If recruiters are – in fact – cognizant of recruits’ role

engulfed status, such construction helps meet the primary goal of securing a recruit’s

commitment. As any good salesperson does, recruiters read and play to recruits’ wants,

need and desires.

31

Table 2.1: Top-Ten Power-5 Athletic Department Revenues-Expenses

Rank

University

Conference

Total Revenues

Total Expenses

1

Texas

Big XII

$214,830,647

$207,022,323

2

Texas A&M

SEC

$211,960,034

$146,546,229

3

Ohio State

Big Ten

$185,409,602

$173,507,435

4

Michigan

Big Ten

$185,173,187

$175,425,392

5

Alabama

SEC

$174,307,419

$158,646,962

6

Georgia

SEC

$157,852,479

$119,218,908

7

Oklahoma

Big XII

$155,238,481

$132,910,780

8

Florida

SEC

$149,165,475

$131,789,499

9

LSU

SEC

$147,744,233

$131,717,421

10

Auburn

SEC

$147,511,034

$132,885,979

Note. (Flaherty, 2018, 247sports.com).

32

Table 2.2: 2019 Power Conference Revenue Distributions

Conference

2019 Distribution

Per-member

Big Ten

$760 million

$54.0 million

SEC

$660 million

$43.7 million

Big XII

$374 million

$34-37 million

Pac-12

$354 million

$29.5 million

ACC

$465 million

$29.5 million

Annual Revenues

$2.75 billion

33

Table 2.3: Codes Examples & Themes

Code Example

Theme

Equipment Sizing with Head Equipment Manager [name omitted] &

Photo Shoot with Sports Information Director [name omitted]

Athletic

Meet with Staff to review Strength and Conditioning plan

Athletic

Observe team shoot-around

Athletic

College of Business. Meeting w/ Professor

Academic

Attend History Class with [name omitted]

Academic

Tour the Academic Center with Academic Advisor, Staff

Academic

Game night with the women's team!

Social

Breakfast at the Hotel with Girls and their families

Social

Walk to [football game]; Recruits on Field [for pregame]

Social

*Note. Codes represent examples taken verbatim from itineraries. Bracketed items

indicate names of individuals, universities, or facilities that have been removed to

maintain anonymity.

34

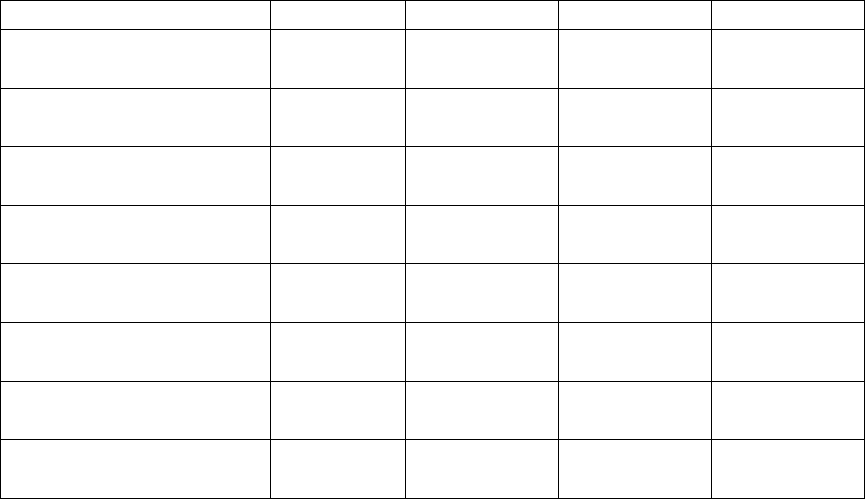

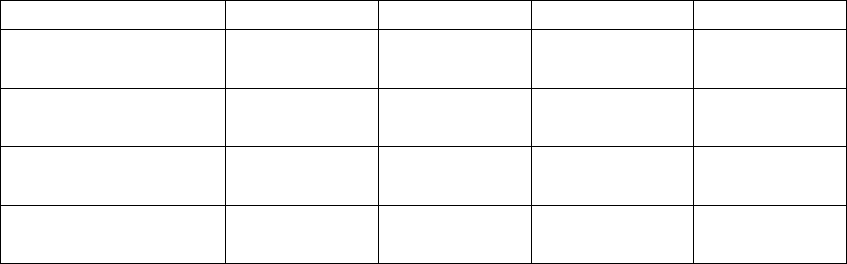

Table 2.4: Sport Findings

Sport

n

Athletic

Items

Athletic

Time

Academic

Items

Academic

Times

Social

Items

Social

Time

Equestrian

1

5.0

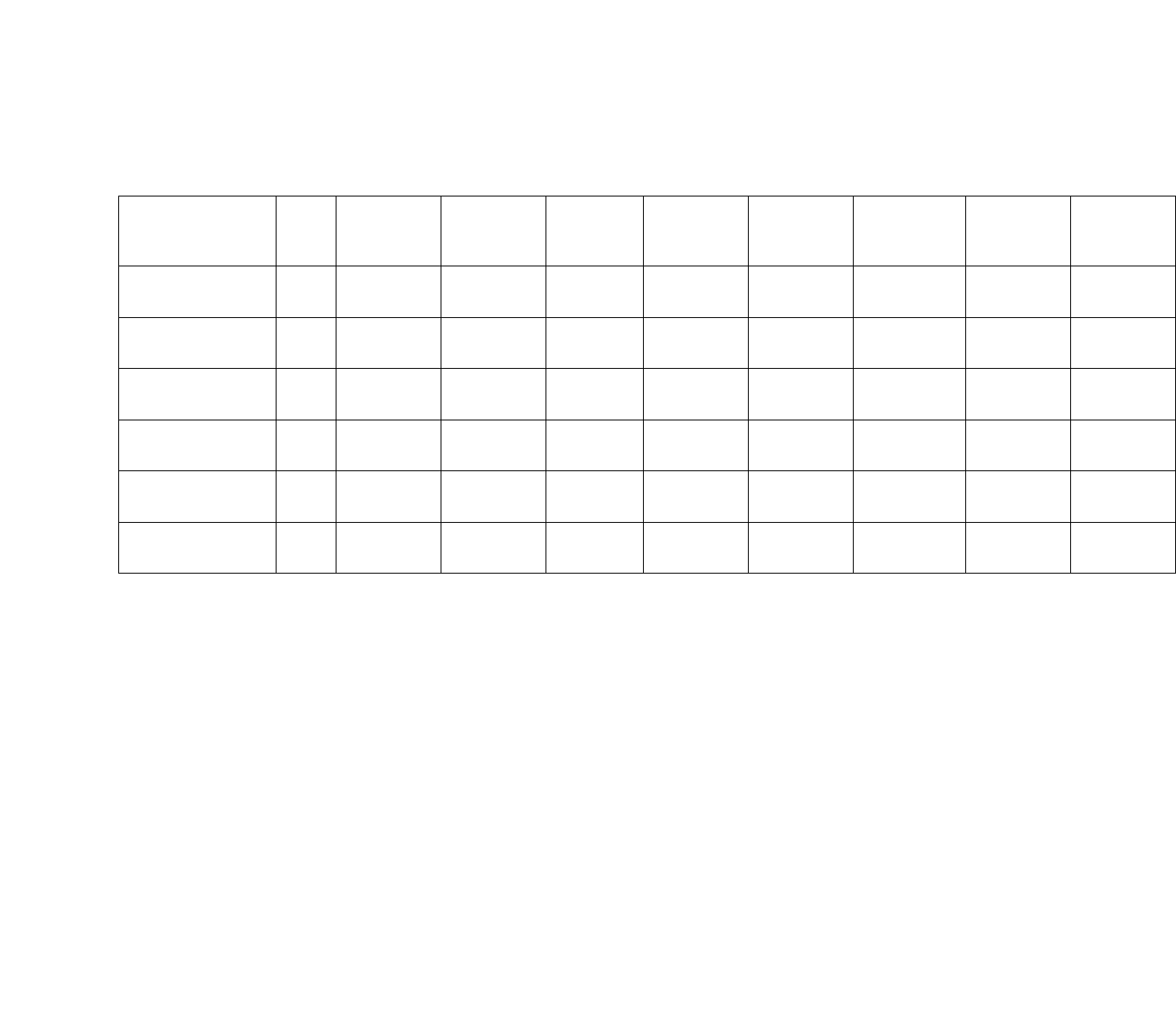

6:05

4.0

6:35

8.0

12:55

Rifle

1

4.0

11:00

2.0

6:30

6.0

5:30

Lacrosse

1

1.0

0:00

1.0

2:15

9.0

4:25

Track & Field

(Women's)

5

4.0

6:50

1.8

2:03

9.8

10:32

Track & Field

(Men's)

5

4.4

5:57

1.8

2:00

8.6

12:28

Swimming &

Diving (Men's)

3

5.7

6:06

1.3

1:26

6.7

13:20

Swimming &

Diving

(Women's)

6

5.5

7:09

1.5

1:24

8.3

10:59

Golf

(Women's)

4

2.0

2:26

1.0

1:17

7.5

8:38

Gymnastics

3

3.7

5:50

1.0

1:05

8.3

14:35

Football

7

6.6

3:59

1.7

0:58

11.4

14:23

Basketball

(Women's)

3

4.3

4:10

1.3

0:51

11.7

10:48

Tennis

(Women's)

4

3.3

5:35

1.3

0:51

7.3

8:48

Softball

5

2.6

3:08

1.2

0:46

8.8

10:37

Tennis (Men's)

4

4.3

4:33

1.0

0:45

7.8

8:05

Wrestling

1

4.0

4:15

1.0

0:30

10.0

11:25

Basketball

(Men's)

4

4.8

7:06

0.8

0:26

7.8

8:18

Golf (Men's)

4

2.5

3:41

0.5

0:26

6.5

11:37

Soccer

5

4.8

4:41

0.6

0:24

8.6

10:55

Baseball

5

3.8

4:22

0.4

0:15

6.2

11:00

Volleyball

4

3.5

3:18

0.8

0:15

5.0

5:00

35

Beach

Volleyball

1

2.0

6:00

0.0

0:00

4.0

8:30

*Note. Figures represent calculated averages in cases where n>1.

36

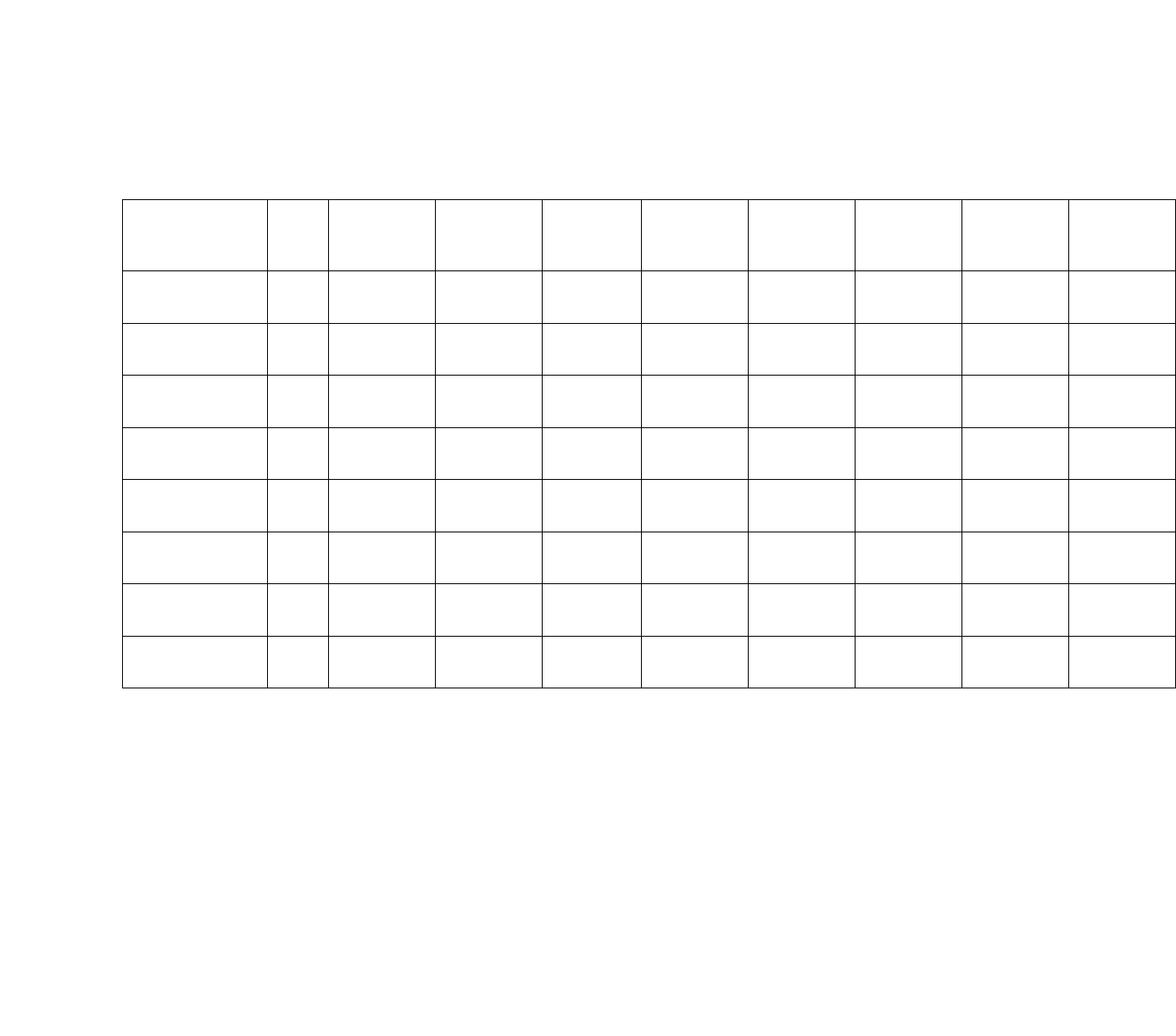

Table 2.5: Summary Statistics

Group

n

Athletic

Items

Athletic

Time

Academic

Items

Academic

Times

Social

Items

Social

Time

All Sports

76

4.1

4:58

1.2

1:06

8.2

10:35

Men’s Sports

33

4.7

4:57

1.1

0:53

8.2

11:33

Women’s