!

1!

May 2017, Special Issue

Comparing Health-Related Policies and Practices in Sports:

The NFL and Other Professional Leagues

Christopher R. Deubert, I. Glenn Cohen, and Holly Fernandez Lynch

This is a special version of Comparing Health-Related Policies and Practices in Sports: The NFL and

Other Professional Leagues (“the Report”). The Report, part of the Football Players Health Study at

Harvard University, was self-published in May 2017 and can be found on this website:

footballplayershealth.harvard.edu or through Amazon.com. This version is being published through the

Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law (“JSEL”) to ensure the Report is accessible to

attorneys, law students, the legal community and other academic audiences.

There are ways in which this version is different from the initially published Report and a typical JSEL

article. While several JSEL students were involved in cite checking the majority of the Report, JSEL did

not cite check the entire Report. This possible deficiency was compensated by the Report’s extensive

review and fact checking process, as described in the Introduction. Additionally, the actual Report was

professionally designed, including color graphics and other design elements which could not be included

here. The endnotes were formatted in such a way as to aid the design process and thus do not necessarily

match the style outlined in The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (20th ed. 2015).

!

2!

TABLE CONTENTS

ENSURING INDEPENDENCE AND DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS ................................... 11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 13

PREFACE: The Football Players Health Study at Harvard University ........................................ 25

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 28

A. The Leagues ..................................................................................................................... 28

B. The Unions ....................................................................................................................... 29

C. Collective Bargaining Agreements ................................................................................ 30

D. Audience........................................................................................................................... 31

E. Goals and Process ........................................................................................................... 32

1. Identify ....................................................................................................................... 32

2. Describe ..................................................................................................................... 32

3. Evaluate ..................................................................................................................... 34

4. Recommend ............................................................................................................... 34

F. Scope................................................................................................................................. 35

CHAPTER 1: CLUB MEDICAL PERSONNEL ......................................................................... 36

A. Club Medical Personnel in the NFL .............................................................................. 39

1. Types of Medical Personnel ..................................................................................... 39

2. Medical Personnel’s Obligations ............................................................................. 40

3. Players’ Obligations ................................................................................................. 42

4. Relationship between Medical Personnel and Clubs ............................................ 42

5. Sponsorship Arrangements ..................................................................................... 43

B. Club Medical Personnel in MLB ................................................................................... 46

1. Types of Medical Personnel ..................................................................................... 46

2. Medical Personnel’s Obligations ............................................................................. 48

3. Players’ Obligations ................................................................................................. 49

4. Relationship between Medical Personnel and Clubs ............................................ 50

5. Sponsorship Arrangements ..................................................................................... 51

C. Club Medical Personnel in the NBA ............................................................................. 51

1. Types of Medical Personnel ..................................................................................... 51

2. Medical Personnel’s Obligations ............................................................................. 53

3. Players’ Obligations ................................................................................................. 54

!

3!

4. Relationship between Medical Personnel and Clubs ............................................ 56

5. Sponsorship Arrangements ..................................................................................... 57

D. Club Medical Personnel in the NHL ............................................................................. 57

1. Types of Medical Personnel ..................................................................................... 57

2. Medical Personnel’s Obligations ............................................................................. 59

3. Players’ Obligations ................................................................................................. 60

4. Relationship between Medical Personnel and Clubs ............................................ 61

5. Sponsorship Arrangements ..................................................................................... 61

E. Club Medical Personnel in the CFL .............................................................................. 62

1. Types of Medical Personnel ..................................................................................... 62

2. Medical Personnel’s Obligations ............................................................................. 62

3. Players’ Obligations ................................................................................................. 63

4. Relationship between Medical Personnel and Clubs ............................................ 63

5. Sponsorship Arrangements ..................................................................................... 63

F. Club Medical Personnel in MLS ................................................................................... 64

1. Types of Medical Personnel ..................................................................................... 64

2. Medical Personnel’s Obligations ............................................................................. 65

3. Players’ Obligations ................................................................................................. 66

4. Relationship with Clubs ........................................................................................... 67

5. Sponsorship Arrangements ..................................................................................... 68

G. Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 68

H. Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 71

CHAPTER 2: INJURY RATES AND POLICIES ....................................................................... 72

A. Injuries in the NFL ......................................................................................................... 75

1. Injury Tracking System ........................................................................................... 75

2. Injury Statistics ......................................................................................................... 76

3. Injury-Related Lists ................................................................................................. 79

4. Injury Reporting Policies ......................................................................................... 80

B. Injuries in MLB .............................................................................................................. 81

1. Injury Tracking System ........................................................................................... 81

2. Injury Statistics ......................................................................................................... 81

3. Injury-Related Lists ................................................................................................. 83

4. Injury Reporting Policies ......................................................................................... 83

C. Injuries in the NBA ......................................................................................................... 84

!

4!

1. Injury Tracking System ........................................................................................... 84

2. Injury Statistics ......................................................................................................... 84

3. Injury-Related Lists ................................................................................................. 86

4. Injury Reporting Policies ......................................................................................... 86

D. Injuries in the NHL ......................................................................................................... 86

1. Injury Tracking System ........................................................................................... 86

2. Injury Statistics ......................................................................................................... 86

3. Injury-Related Lists ................................................................................................. 88

4. Injury Reporting Policies ......................................................................................... 89

E. Injuries in the CFL ......................................................................................................... 89

1. Injury Tracking System ........................................................................................... 89

2. Injury Statistics ......................................................................................................... 89

3. Injury-Related Lists ................................................................................................. 90

4. Injury Reporting Policies ......................................................................................... 90

F. Injuries in MLS ............................................................................................................... 90

1. Injury Tracking System ........................................................................................... 90

2. Injury Statistics ......................................................................................................... 90

3. Injury-Related Lists ................................................................................................. 92

4. Injury Reporting Policies ......................................................................................... 92

G. Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 92

H. Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 97

CHAPTER 3: HEALTH-RELATED BENEFITS ...................................................................... 100

A. NFL Health-Related Benefits ....................................................................................... 103

1. Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................ 104

2. Insurance Benefits .................................................................................................. 107

3. Disability Benefits ................................................................................................... 108

4. Workers’ Compensation Benefits ......................................................................... 110

5. Education-Related Benefits ................................................................................... 110

6. Joint Health-Specific Committees ......................................................................... 110

B. MLB Health-Related Benefits ...................................................................................... 111

1. Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................ 111

2. Insurance Benefits .................................................................................................. 113

3. Disability Benefits ................................................................................................... 113

4. Workers’ Compensation Benefits ......................................................................... 114

!

5!

5. Education-Related Benefits ................................................................................... 114

6. Joint Health-Specific Committees ......................................................................... 114

C. NBA Health-Related Benefits ...................................................................................... 114

1. Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................ 114

2. Insurance Benefits .................................................................................................. 115

3. Disability Benefits ................................................................................................... 116

4. Workers’ Compensation Benefits ......................................................................... 116

5. Education-Related Benefits ................................................................................... 117

6. Joint Health-Specific Committees ......................................................................... 117

D. NHL Health-Related Benefits ...................................................................................... 118

1. Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................ 118

2. Insurance Benefits .................................................................................................. 119

3. Disability Benefits ................................................................................................... 119

4. Workers’ Compensation Benefits ......................................................................... 120

5. Education-Related Benefits ................................................................................... 120

6. Joint Health-Specific Committees ......................................................................... 120

E. CFL Health-Related Benefits ........................................................................................... 120

1. Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................ 120

2. Insurance Benefits .................................................................................................. 120

3. Disability Benefits ................................................................................................... 121

4. Workers’ Compensation Benefits ......................................................................... 121

5. Education-Related Benefits ................................................................................... 121

6. Joint Health-Specific Committees ......................................................................... 121

F. MLS Health-Related Benefits ...................................................................................... 121

1. Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................ 121

2. Insurance Benefits .................................................................................................. 121

3. Disability Benefits ................................................................................................... 122

4. Workers’ Compensation Benefits ......................................................................... 122

5. Education-Related Benefits ................................................................................... 122

6. Joint Health-Specific Committees ......................................................................... 122

G. Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 122

H. Recommendation ........................................................................................................... 126

CHAPTER 4: DRUG AND PERFORMANCE-ENHANCING SUBSTANCE POLICIES ...... 127

A. The NFL’s Drug Policies .............................................................................................. 129

!

6!

1. Substances Prohibited ............................................................................................ 130

2. Types of Tests and Prohibited Conduct ............................................................... 130

3. Number of Tests ...................................................................................................... 131

4. Administration ........................................................................................................ 132

5. Therapeutic Use ...................................................................................................... 132

6. Treatment ................................................................................................................ 133

7. Discipline ................................................................................................................. 134

8. Confidentiality ........................................................................................................ 135

B. MLB’s Drug Policies ..................................................................................................... 136

1. Substances Prohibited ............................................................................................ 136

2. Types of Tests and Prohibited Conduct ............................................................... 136

3. Number of Tests ...................................................................................................... 136

4. Administration ........................................................................................................ 137

5. Therapeutic Use ...................................................................................................... 137

6. Treatment ................................................................................................................ 137

7. Discipline ................................................................................................................. 138

8. Confidentiality ........................................................................................................ 139

C. The NBA’s Drug Policies .............................................................................................. 139

1. Substances Prohibited ............................................................................................ 139

2. Types of Tests and Prohibited Conduct ............................................................... 139

3. Number of Tests ...................................................................................................... 140

4. Administration ........................................................................................................ 140

5. Therapeutic Use ...................................................................................................... 140

6. Treatment ................................................................................................................ 140

7. Discipline ................................................................................................................. 141

8. Confidentiality ........................................................................................................ 142

D. The NHL’s Drug Policies .............................................................................................. 143

1. Substances Prohibited ............................................................................................ 143

2. Types of Tests and Prohibited Conduct ............................................................... 143

3. Number of Tests ...................................................................................................... 144

4. Administration ........................................................................................................ 144

5. Therapeutic Use ...................................................................................................... 145

6. Treatment ................................................................................................................ 145

7. Discipline ................................................................................................................. 145

!

7!

8. Confidentiality ........................................................................................................ 146

E. The CFL’s Drug Policies .............................................................................................. 147

1. Substances Prohibited ............................................................................................ 147

2. Types of Tests and Prohibited Conduct ............................................................... 147

3. Number of Tests ...................................................................................................... 147

4. Administration ........................................................................................................ 148

5. Therapeutic Use ...................................................................................................... 148

6. Treatment ................................................................................................................ 148

7. Discipline ................................................................................................................. 148

8. Confidentiality ........................................................................................................ 149

F. MLS’ Drug Policies ....................................................................................................... 149

1. Substances Prohibited ............................................................................................ 149

2. Types of Tests and Prohibited Conduct ............................................................... 149

3. Number of Tests ...................................................................................................... 150

4. Administration ........................................................................................................ 150

5. Therapeutic Use ...................................................................................................... 150

6. Treatment ................................................................................................................ 150

7. Discipline ................................................................................................................. 151

8. Confidentiality ........................................................................................................ 151

G. Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 151

H. Recommendation ........................................................................................................... 154

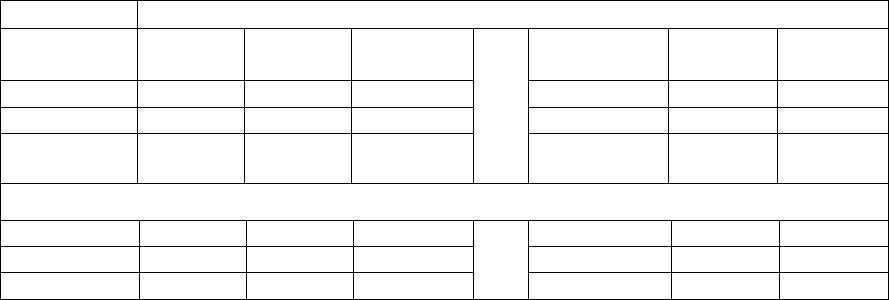

CHAPTER 5: COMPENSATION .............................................................................................. 155

A. Compensation in the NFL ............................................................................................ 157

1. The NFL’s Salary Cap ........................................................................................... 157

2. Rookie Compensation ............................................................................................ 158

3. Veteran Compensation ........................................................................................... 159

4. Minimum, Maximum, and Average (Mean) Salaries .......................................... 160

5. Guaranteed Compensation .................................................................................... 161

B. Compensation in MLB ................................................................................................. 163

1. MLB’s Tax Threshold ............................................................................................ 163

2. Rookie Compensation ............................................................................................ 164

3. Veteran Compensation ........................................................................................... 164

4. Minimum, Maximum, and Average (Mean) Salaries .......................................... 165

5. Guaranteed Compensation .................................................................................... 166

!

8!

C. Compensation in the NBA ............................................................................................ 166

1. The NBA’s Salary Cap ........................................................................................... 166

2. Rookie Compensation ............................................................................................ 167

3. Veteran Compensation ........................................................................................... 168

4. Minimum, Maximum, and Average (Mean) Salaries .......................................... 169

5. Guaranteed Compensation .................................................................................... 171

D. Compensation in the NHL ........................................................................................... 172

1. The NHL’s Salary Cap ........................................................................................... 172

2. Rookie Compensation ............................................................................................ 173

3. Veteran Compensation ........................................................................................... 173

4. Minimum, Maximum, and Average (Mean) Salaries .......................................... 174

5. Guaranteed Compensation .................................................................................... 175

E. Compensation in the CFL ............................................................................................ 175

1. The CFL’s Salary Cap ........................................................................................... 175

2. Rookie Compensation ............................................................................................ 176

3. Veteran Compensation ........................................................................................... 176

4. Minimum, Maximum, and Average (Mean) Salaries .......................................... 176

5. Guaranteed Compensation .................................................................................... 177

F. Compensation in MLS .................................................................................................. 178

1. MLS’ Salary Cap .................................................................................................... 179

2. Rookie Compensation ............................................................................................ 179

3. Veteran Compensation ........................................................................................... 179

4. Minimum, Maximum, and Average (Mean) Salaries .......................................... 179

5. Guaranteed Compensation .................................................................................... 179

G. Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 180

H. Recommendation ........................................................................................................... 181

CHAPTER 6: ELIGIBILITY RULES ........................................................................................ 182

A. Player Eligibility Rules in the NFL ............................................................................. 186

B. Player Eligibility Rules in MLB .................................................................................. 189

C. Player Eligibility Rules in the NBA ............................................................................. 192

D. Player Eligibility Rules in the NHL ............................................................................. 194

E. Player Eligibility Rules in the CFL ............................................................................. 196

F. Player Eligibility Rules in MLS ................................................................................... 197

G. Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 198

!

9!

H. Recommendations ......................................................................................................... 199

CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................... 200

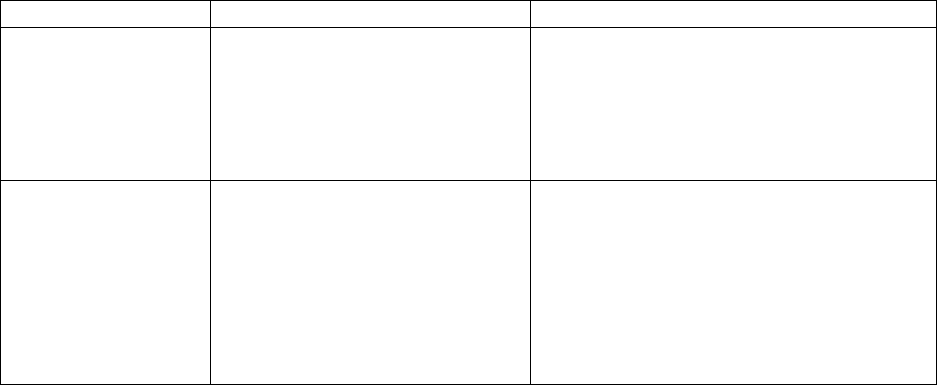

APPENDIX A – COMPILATION OF RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................. 202

I. Club Medical Personnel ............................................................................................... 202

II. Injury Rates and Policies.............................................................................................. 203

III. Health-Related Benefits ............................................................................................. 205

IV. Drug and Performance-Enhancing Drug Policies ................................................... 206

V. Compensation ................................................................................................................ 207

VI. Eligibility Rules .......................................................................................................... 209

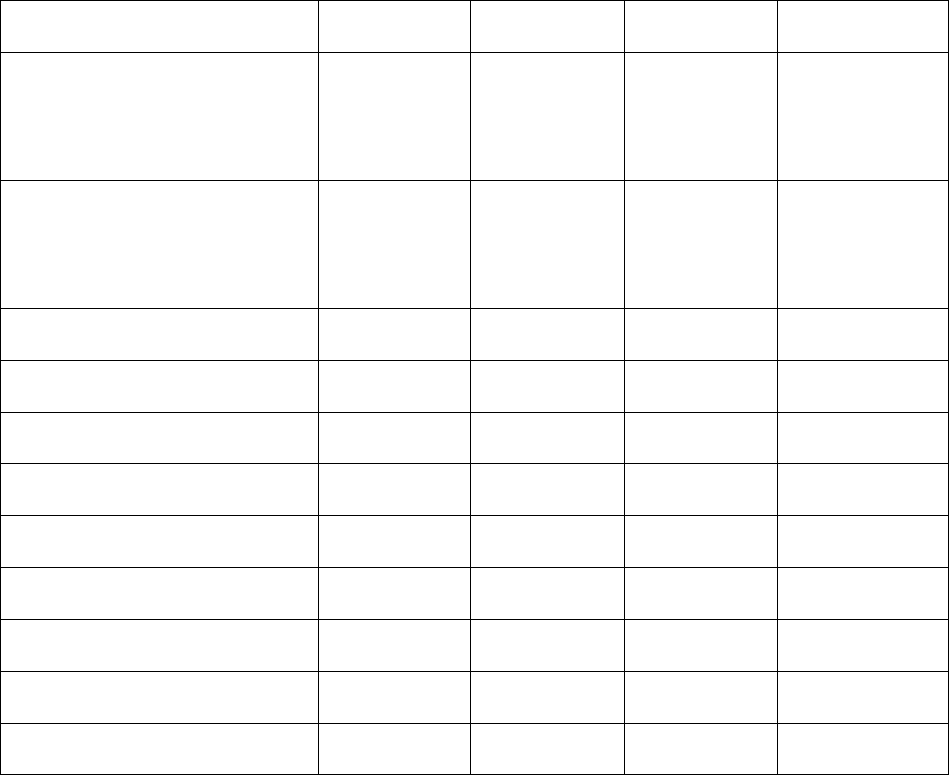

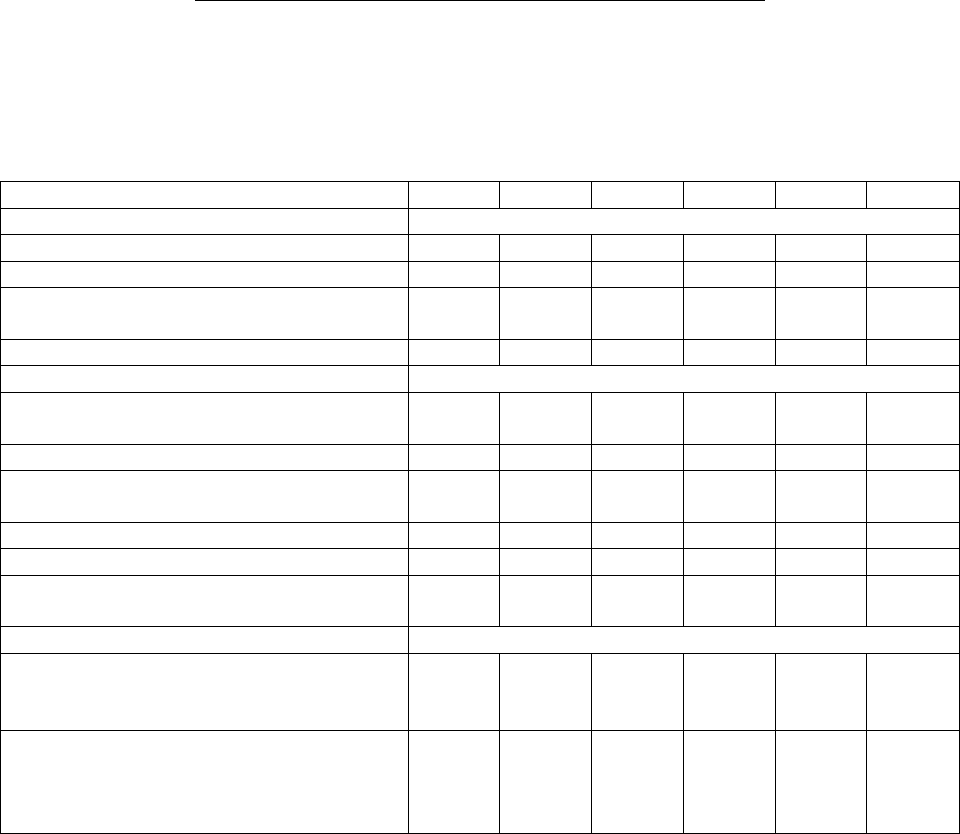

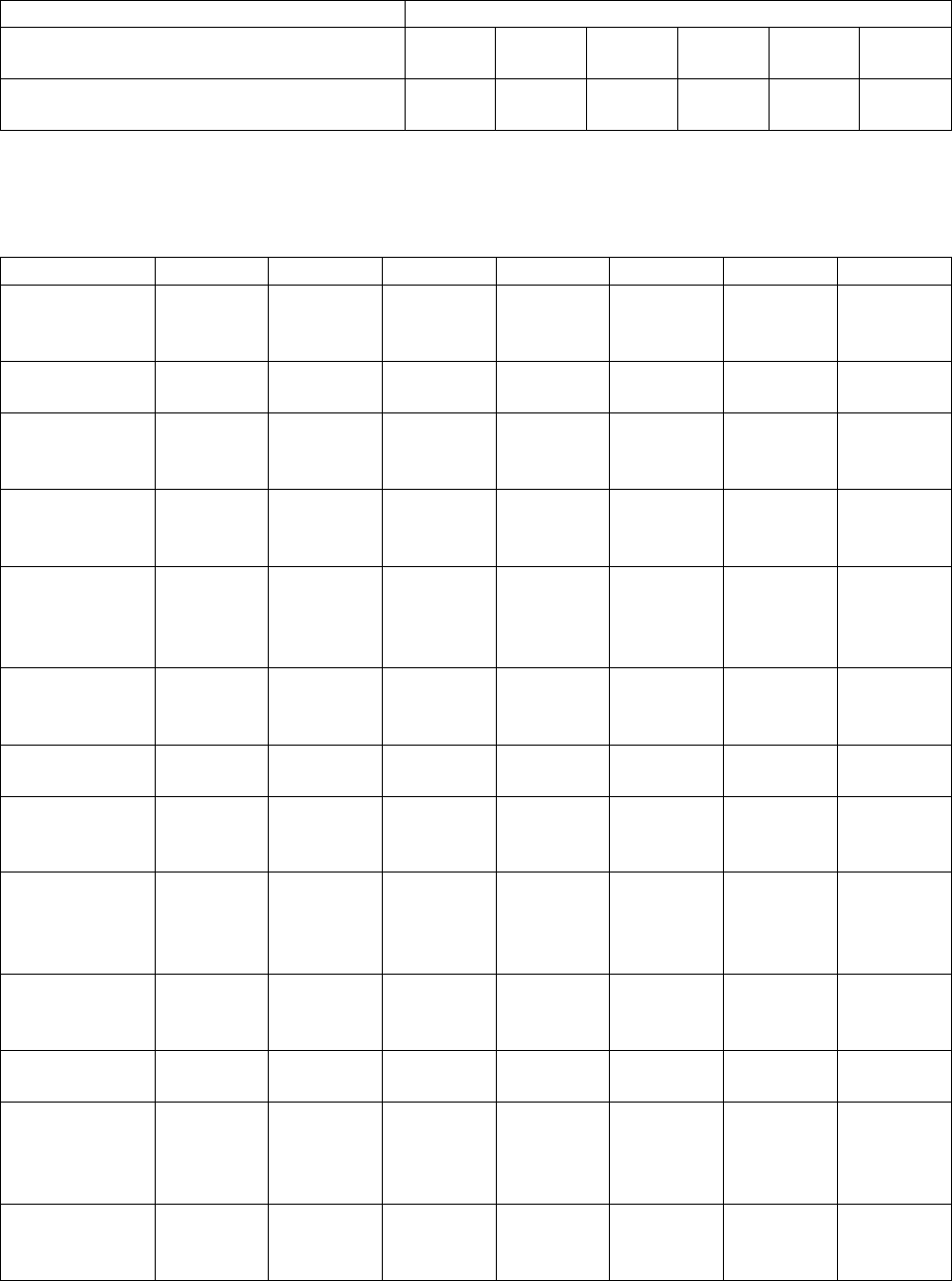

APPENDIX B – COMPILATION OF SUMMARY TABLES .................................................. 210

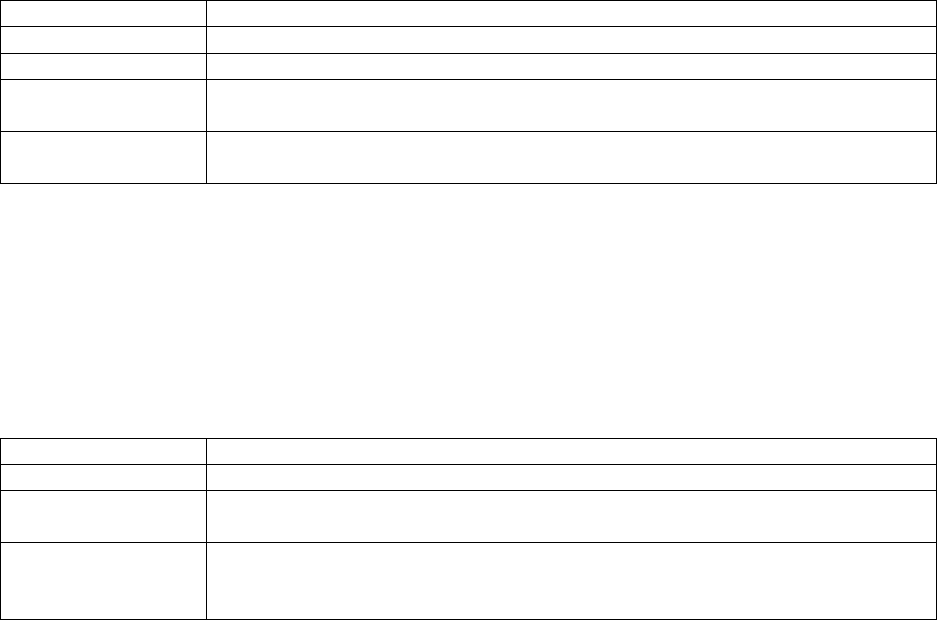

APPENDIX C – GLOSSARY OF TERMS AND RELEVANT PERSONS AND

INSTITUTIONS ......................................................................................................................... 214

About the Authors

Christopher R. Deubert is the Senior Law and Ethics Associate for the Law and Ethics Initiative of the

Football Players Health Study at Harvard University. Previously, Deubert practiced commercial litigation,

sports law, securities litigation, and labor/employment litigation at Peter R. Ginsberg Law, LLC f/k/a

Ginsberg & Burgos, PLLC in New York City. His sports practice focused primarily on representing

National Football League (NFL) players in League matters, including appeals for Commissioner

Discipline, under the NFL’s Policy and Program on Substances of Abuse and under the NFL’s Policy on

Anabolic Steroids and Related Substances (now known as the Policy on Performance-Enhancing

Substances), and related litigation. Deubert also previously worked for Sportstars, Inc., one of the largest

NFL-player representation firms, performing contract, statistical, and legal analysis, and he performed

similar work during an internship with the New York Jets. Deubert graduated with a joint

JD/MBA degree from Fordham University School of Law and Graduate School of Business in 2010, and

a BS in Sport Management from the University of Massachusetts in 2006.

I. Glenn Cohen is a professor at Harvard Law School; Faculty Director of the Petrie-Flom Center for

Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics; and, Co-Lead of the Law and Ethics Initiative of the

Football Players Health Study. His award-winning work at the intersection of law, medicine, and ethics—

in particular, medical tourism and assisted reproduction—has been published in leading journals, such as

the Harvard Law Review, Stanford Law Review, New England Journal of Medicine, Journal of the

American Medical Association, American Journal of Bioethics, and American Journal of Public Health.

He was previously a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and a faculty scholar in

bioethics with the Greenwall Foundation. He is the author, editor, and/or co-editor of several books from

Oxford, Columbia, John Hopkins, and MIT University Presses. Prior to joining the Harvard faculty,

Cohen served as a clerk to Chief Judge Michael Boudin, United States Court of Appeals for the First

Circuit, and as an appellate lawyer in the Civil Division of the Department of Justice. He graduated from

the University of Toronto with a BA (with distinction) in Bioethics (Philosophy) and Psychology and

earned his JD from Harvard Law School.

Holly Fernandez Lynch is Executive Director of the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy,

Biotechnology, and Bioethics; Faculty at the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics; and, Co-Lead

!

10!

of the Law and Ethics Initiative of the Football Players Health Study. Her scholarly work focuses on the

regulation and ethics of human subjects research and issues at the heart of the doctor-patient relationship.

Her book, Conflicts of Conscience in Health Care: An Institutional Compromise, was published by MIT

Press in 2008; she is also co-editor with I. Glenn Cohen of Human Subjects Research Regulation:

Perspectives on the Future (MIT Press 2014), FDA in the 21st Century: The Challenges of Regulating

Drugs and New Technologies (Columbia University Press 2015), and Nudging Health: Health Law and

Behavioral Economics (Johns Hopkins University Press 2016). Lynch practiced pharmaceuticals law at

Hogan & Hartson, LLP (now Hogan Lovells), in Washington, DC, and worked as a bioethicist in the

Human Subjects Protection Branch at the National Institutes of Health’s Division of AIDS. She also

served as senior policy and research analyst for President Obama’s Commission for the Study of

Bioethical Issues. Lynch is currently a member of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human

Research Protections at the US Department of Health and Human Services. She graduated Order of the

Coif from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, where she was a Levy Scholar in Law and

Bioethics. She earned her master’s degree in bioethics from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of

Medicine, and her BA with a concentration in bioethics, also from the University of Pennsylvania.

!

11!

Acknowledgements

First, the authors would like to thank the staff and research assistants who assisted in the creation of this

Report: Daniel Ain; Tom Blackmon; Jay Cohen; Louis Fisher; Nicholas Hidalgo; Scott Sherman; Jamie

Smith-George; and, Samuel Stuckey. These individuals assisted with a variety of administrative and

research tasks. Relatedly, the authors would like to thank Professor Peter Carfagna for helping to

coordinate research assistance by his students. Particular thanks are due to Justin Leahey, Project

Coordinator for the Law & Ethics Initiative of the Football Players Health Study, who provided important

administrative and research assistance throughout the creation of the Report.

Second, the authors would like to thank the members of the Law & Ethics Advisory Panel for their

comments and guidance during the creation of this Report: Nita Farahany; Joseph Fins; Ashley Foxworth;

Walter Jones; Isaiah Kacyvenski; Bernard Lo; Chris Ogbonnaya; and, Dick Vermeil.

Third, the authors would like to thank the expert reviewers of this Report who provided valuable

comments during the editing process: Marc Edelman, Zicklin School of Business, Baruch College, City

University of New York; and, Michael McCann, University of New Hampshire School of Law.

Fourth, the authors would like to thank the professors and academic professionals who reviewed and

provided comments for parts of this Report: Neil Longley; Stephanie Morain; and, Karen Roos.

Relatedly, the authors would like to thank The Hastings Center, who initially proposed the idea of this

Report.

Fifth, the authors would like to thank the professionals who helped finalize this Report: Lori Shridhare

from the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University; Cristine Hutchison-Jones, who provided

proofreading and editing services; and, Fassino/Design, Inc., which designed and formatted the Report.

Finally, the authors would like to thank the leagues and players unions that agreed to provide relevant

information and/or review this Report prior to its publication. In the Introduction, we provide more detail

as to those leagues and unions that provided relevant information and/or reviewed this Report prior to its

publication. The cooperation of the leagues and players unions was essential to the accuracy, fairness, and

comprehensiveness of this Report.

ENSURING INDEPENDENCE AND DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS

The 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreement between the National Football League Players Association

(“NFLPA”) and the National Football League (“NFL”) set aside funds for medical research. The NFLPA

directed a portion of those funds to create the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University, of

which this Report is a part. Our analysis has been independent of any controlling interest by the NFLPA,

the NFL, or any other party; this independence was contractually protected in Harvard’s funding

agreement with the NFLPA. Per that contract, the NFLPA was only entitled to prior review of this Report

to ensure that no confidential information was disclosed.

1

Additional information about how this Report

came to be is provided in the Preface.

The present Report is part of the Law and Ethics Initiative of the Football Players Health Study at

Harvard University. Additional background information about the Football Players Health Study is

provided in the Preface. We provide more specific information about the Law and Ethics Initiative here.

!

12!

The Statement of Work agreed to between the NFLPA and Harvard included as one of the Law and Ethics

Initiative’s projects to “Conduct Comparative Sports League Analysis.” More specifically, Harvard

described the work to be done as follows:

We will analyze governance and stakeholder obligations in other

professional sports leagues in order to identify best practices and situate

the ethics framework developed for professional football. This project

will examine, for example, how medical practices in other leagues may

result in the encouragement and tolerance of behavior that is risky to

health. The project will examine influences among health behaviors of

players and team policies regarding player health.

This project description was intended to be preliminary. The actual scope of this Report developed over

time, as expected, as the result of considerable research, internal discussion, and conversations with

experts. Beyond agreeing to the Statement of Work, the NFLPA did not direct the scope or content of this

Report.

As is typical with sponsored research, we provided periodic updates to the sponsor in several formats:

Pursuant to the terms of Harvard-NFLPA agreement, the NFLPA does receive an annual report on the

progress of the Football Players Health Study as well as one Quad Chart progress report each year.

Additionally, on two occasions (August 22, 2014, and January 23, 2015), we presented a summary of the

expected scope and content of the Report to the Football Players Health Study Executive Committee,

comprised of both Harvard and NFLPA personnel. Those meetings did not alter our approach in

constructing this Report, the conclusions reached, or the recommendations made. Moreover, none of the

comments made during those meetings altered the content of the Report.

In the Introduction, Section E(2): Describe, we discuss our research process for this Report. Additional

information about our communications with the NFLPA and NFL is also relevant here. During the course

of our research, we had multiple telephone and email communications with both NFLPA and NFL

representatives to gain factual information. These communications were not about the progress, scope, or

structure of our Report.

We also concluded that it was essential to provide the applicable stakeholders the opportunity to

substantively review the Report. These stakeholders are the leagues discussed in this Report: the National

Football League (“NFL”); Major League Baseball (“MLB”); the National Basketball Association

(“NBA”); the National Hockey League (“NHL”); the Canadian Football League (“CFL”); and, Major

League Soccer (“MLS”). This was necessary to try to fully account for the realities at hand, avoid factual

errors, and fairly consider all sides. Accordingly, we provided each league the opportunity to review the

Report before publication. Additional information about the leagues’ and their corresponding labor

unions’ cooperation with and review of this Report or failure to do so is included in the Introduction,

Section 6(C): Limitations.

The leagues had the opportunity to identify any errors, provide additional information, comment on what

action we expected from them going forward, and raise further suggestions or objections. Sometimes

these comments led to valuable changes in the Report. We found other comments unpersuasive and they

did not result in any changes. It is critical to recognize that no external party, including the NFLPA and

NFL, had the ability to direct or alter our analysis or conclusions.

In addition, we subjected the draft Report to peer review by outside experts. We engaged two independent

experts in sports law to review the Report for accuracy, fairness, comprehensibility, and its ability to

positively impact the health of NFL players. These experts were Marc Edelman, Zicklin School of

!

13!

Business, Baruch College, City University of New York, and, Michael McCann, University of New

Hampshire School of Law.

Finally, the content of this Report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the

official views of the NFLPA or Harvard University.

Disclosures:

• The Law and Ethics Initiative’s allocated budget is a total of $1,257,045 over three years, which

funds not only the present Report, but also several other projects.

2

• Deubert’s salary is fully supported by the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University.

From August 2010 to May 2014, Deubert was an associate at the law firm of Peter R. Ginsberg

Law, LLC f/k/a Ginsberg & Burgos, PLLC. During the course of his practice at that firm, Deubert

was involved in several legal matters in which the NFL was an opposing party. Of relevance to

this Report, Deubert represented players disciplined pursuant to the NFL’s Policy and Program on

Substances of Abuse and the Policy on Anabolic Steroids and Related Substances (now known as

the Policy on Performance-Enhancing Substances). Also, since 2007, Deubert has provided

research assistance to the Sports Lawyers Association, whose Board of Directors includes many

individuals with interests related to this work.

Lastly, in March 2017, as this Report’s content was finalized except for incorporating some

changes related to new collective bargaining agreements in MLB and the NBA, and with the Law

& Ethics Initiative of the Football Players Health Study ending in May 2017 as the funding period

came to a close, Deubert communicated with organizations with interests relevant to this work

about potential job opportunities, including law firms that represent sports leagues, unions, and

players. Following finalization of the Report, Deubert also communicated with some of the

sports unions themselves about potential job opportunities. All changes to the Report, including

those that occurred during or after March 2017, were reviewed and approved by Cohen and

Lynch.

• 20% of Cohen’s salary is supported by the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University.

Cohen has no other conflicting interests to report.

• 30% of Lynch’s salary is supported by the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University.

Lynch has no other conflicting interests to report.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

What can the NFL and NFLPA learn from the policies and practices of other elite professional sports

leagues about protecting and promoting player health? This is the fundamental question motivating this

Report, authored by members of the Law & Ethics Initiative of the Football Players Health Study at

Harvard University.

3

This Report, Comparing Health-Related Policies and Practices in Sports: The NFL and Other

Professional Leagues, seeks to answer that question. The leagues share considerable similarities—at their

core, they are organizations that coordinate elite-level athletic competitions for mass audiences. In this

respect, the leagues are competitors within the professional sports industry, with each of them competing

!

14!

for fans’ dollars and attention. The policies by which the leagues operate, and their practices, are thus

often very similar. However, as in any industry, there are also differences between the leagues. This

Report seeks to identify and understand those different policies and practices that have the possibility to

affect player health such that the leagues may be able to learn from one another.

While leagues and their games are different in many important respects, making it impractical and unfair

to opine as a definitive matter on which of the leagues’ policies and practices in their totality best protect

player health, the Report generally concludes that the NFL’s policies concerning player health appear

superior to the other leagues. Nevertheless, through the nine recommendations contained in this Report,

we hope to elucidate several ways in which the NFL can learn from other leagues and further improve

player health.

This Report has four functions. First, to identify the various policies that do or could influence the health

of players in the various leagues. Second, to describe the policies and their relation to protecting and

promoting player health. Third, to evaluate the capacity of these policies to protect and promote player

health, in particular, by comparing policies on similar issues. And fourth, to recommend changes to

policies that affect NFL players grounded in our evaluation of certain approaches taken by other leagues

that appear to be more favorable. Where possible, we perform the same analysis concerning the leagues’

practices related to player health.

In this Executive Summary, we provide only summaries of the key issues discussed in the Report, while

the Report covers more issues and provides more complexity, nuance, and all relevant citations. Appendix

A of the Report is a compilation of the Report’s recommendations with explanatory text and Appendix B

is a compilation of tables summarizing and comparing the leagues’ policies and practices.

In the remainder of this summary Introduction, we identify the leagues and player unions relevant to our

analysis and summarize the areas of potential improvement we found when comparing the policies and

practices of the NFL to the other leagues. Then, we provide a summary of each of the issues analyzed in

the Report: (1) Club Medical Personnel; (2) Injury Rates and Policies; (3) Health-Related Benefits; (4)

Drug and Performance-Enhancing Substance Policies; (5) Compensation; and, (6) Eligibility Rules.

A. The Leagues

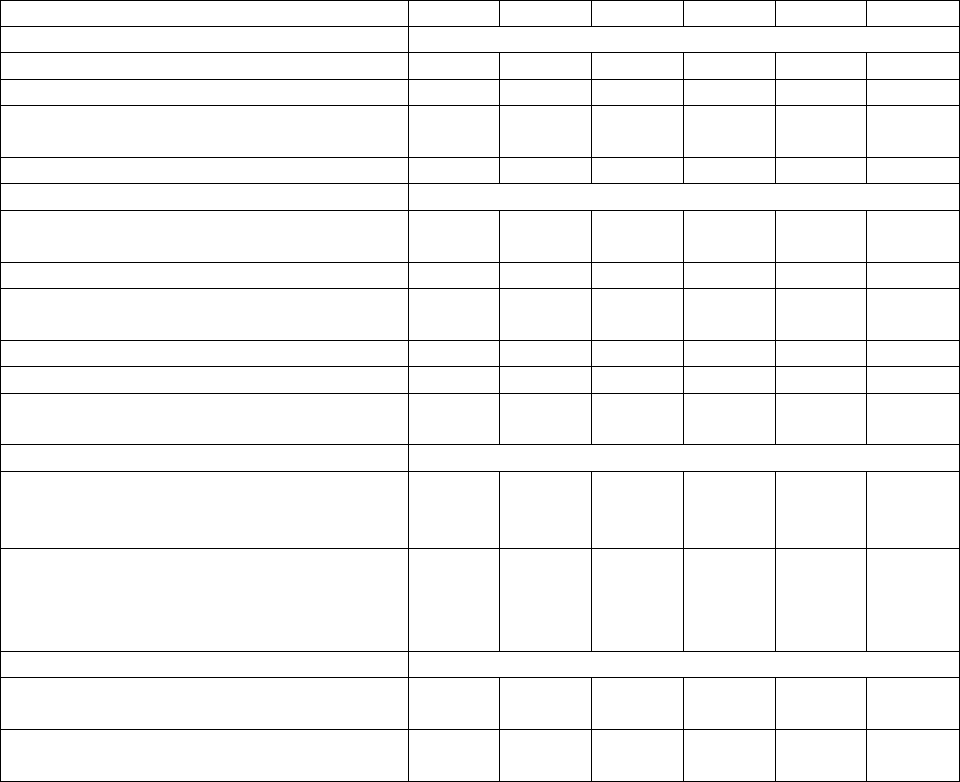

This Report analyzes the policies and practices of the following professional sports leagues:

• The National Football League (“NFL”): The world’s premier professional football league,

consisting of 32 member clubs. The NFL’s 2017 revenues are expected to reach $14 billion.

• Major League Baseball (“MLB”): The world’s premier professional baseball organization,

consisting of 30 member clubs. MLB’s 2016 revenues were an estimated $10 billion.

• National Basketball Association (“NBA”): The world’s premier professional basketball league,

consisting of 30 member clubs. The NBA’s 2016–17 revenues are projected to be approximately

$8 billion.

• National Hockey League (“NHL”): The world’s premier professional hockey league, consisting

of 30 member clubs. The NHL’s 2015–16 revenues were an estimated $4.1 billion.

!

15!

• Canadian Football League (“CFL”): A professional football league consisting of 9 member

clubs, all of which are located in Canada. The CFL’s revenues are an estimated $200 million

annually.

• Major League Soccer (“MLS”): A professional soccer league consisting of 20 clubs. As is

explained in further detail in the Report, MLS is uniquely organized—rather than having each

club owned and controlled by a different person or entity (like in the other sports leagues), all of

the clubs in the MLS are owned and controlled by Major League Soccer, LLC. MLS’ 2016

revenues were an estimated $600 million.

We chose these leagues because of their similarity to the NFL, both structurally and legally. The NFL,

MLB, NBA, and NHL are particularly similar. Each of these leagues has been operating for nearly a

century (or more in the case of MLB) and is an entrenched part of the American sports and cultural

landscape. Their revenue streams also dwarf those of any other professional sports leagues, including the

CFL and MLS. For these reasons, the NFL, MLB, NBA, and NHL are commonly referred to collectively

as the “Big Four” sports leagues. We nevertheless acknowledge that other sports and sports leagues can

provide lessons for the NFL and the other sports leagues concerning player health. The CFL was

included in our analysis because it is the only other long-standing and continuous professional football

league. Finally, the MLS was included because it is a major North American professional sports league.

B. The Unions

Each of the leagues discussed in this Report has an important counterpart. The leagues are the constructs

of the individual clubs (or operator-investors in MLS) and thus are principally interested in protecting and

advancing the rights of the clubs. To protect and advance their rights and interests, the players in each of

the leagues have formed a players association, a labor union empowered with certain rights and

responsibilities under federal labor laws. The players associations are:

• National Football League Players Association (“NFLPA”)

• Major League Baseball Players Association (“MLBPA”)

• National Basketball Players Association (“NBPA”)

• National Hockey League Players Association (“NHLPA”)

• Canadian Football League Players Association (“CFLPA”)

• Major League Soccer Players Union (“MLSPU”)

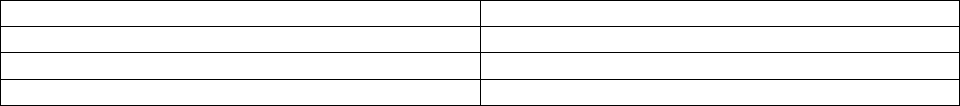

C. Areas for Improvement

As stated earlier, the NFL’s player health provisions are generally the most protective of player health

among the relevant comparators. Nevertheless, we also identified many areas in which the policies and

practices of the NFL concerning player health could potentially be improved by comparison to the other

leagues:

1. The CFL CBA, unlike the NFL CBA, requires that pre-season physicals “to determine the status

of any pre-existing condition” be performed by a neutral physician.

2. The standard of care articulated in the NHL and MLS CBAs, unlike the NFL CBA, seemingly

!

16!

requires club doctors to subjugate their duties to the club to their duties to the player at all times.

3. MLB, unlike the NFL, has a concussion-specific short-term injury list.

4. The MLB, NHL, and CFL injury reporting policies, unlike the NFL, do not require the disclosure

of the location on the body of a player’s injury.

5. MLB, the NBA, and the NHL, unlike the NFL, generally offer health insurance to players for life.

6. Among the Big Four leagues, the retirement plan payments offered by the NFL are the lowest.

7. MLB and NHL players, unlike in those in the NFL, are vested in their pension plans on the first

day they play in the league.

8. The NBA and CFL, unlike the NFL, offer treatment to players who have violated their

performance-enhancing substance policies.

9. The amount of player compensation that is guaranteed in the NFL is substantially lower than in

the other Big Four leagues.

10. The NFL has the most prohibitive eligibility rule of the leagues (except the CFL).

In the full Report, for each of these possible improvements we discuss whether the NFL’s policies might

be justifiably different than the other leagues’.

Chapter 1: Club Medical Personnel

This Chapter discusses the role of club medical staff, including both doctors and athletic trainers, in each

of the sports leagues as set forth in the leagues’ various controlling policies, most principally, their CBAs.

In particular, we focus on: (1) the types of medical personnel required, if any; (2) the medical personnel’s

obligations; (3) the obligations of the players concerning club medical personnel; (4) the relationship

between the medical personnel and the clubs; and, (5) the existence of sponsorship arrangements between

medical personnel and the clubs, if any.

Our focus here is on the structural issues that are generally governed by the CBA or other policies rather

than how each individual club hires and supervises its medical personnel and how individual medical

personnel interact with individual players, matters that are not the subject of extensive reporting or

publicly available research. By understanding what is required or permitted pursuant to the CBA or other

policies we can understand the scope of possible practices, including those that might be concerning as

they relate to player health.

Our analysis suggests that the NFL’s policies concerning club medical personnel are overall, by

comparison to the other leagues, the most protective of player health in almost all cases by providing

players with superior control and information about their healthcare. Nevertheless, there are four areas in

which the NFL might appear deficient as compared to one or more of the other leagues. Two of these

apparent deficiencies (access to medical records and prescription medication monitoring) are not a

problem in practice. We believe that a third deficiency – the inherent conflict of interest in the structure

of club medical staffs and related standard of care provisions – are not adequately addressed by any of the

leagues. This issue and our proposed recommendation is discussed at length in our report Protecting and

Promoting the Health of NFL Players: Legal and Ethical Analysis and Recommendations. Thus, here, we

focus on the lone issue resulting in a recommendation for the NFL.

While the CFL Standard Player Contract requires players to submit to a pre-season physical by the club’s

doctors, the CFL CBA also requires that pre-season physicals “to determine the status of any pre-existing

condition” be performed by a neutral physician. The stated purpose of this requirement is to help

determine “in the future” whether there was “an aggravation of… [a] pre-existing condition.” In contrast,

NFL club doctors perform all pre-season physicals and would be the ones to opine about a player’s prior

!

17!

injury history. We believe the CFL’s approach is preferred, and thus recommend that the NFL consider

adopting such an approach:

• Recommendation 1-A: Pre-season physicals for the purpose of evaluating a player’s prior

injuries should be performed by neutral doctors.

Chapter 2: Injury Rates and Policies

An important measurement of player health is the incidence and type of injuries players may sustain in

the course of their work. Additionally, given the importance of player injuries, the manner in which

player injuries are handled administratively and reported can indicate a league’s approach to player health

issues more generally. In this Chapter, we examine the leagues’: (1) injury tracking systems; (2) injury

rates; (3) injury-related lists; and, (4) policies concerning public reporting of injuries. In summarizing our

analysis, it is important to note that there are important limitations in analyzing and comparing the

leagues’ injury data, described at length in the full Report, including but not limited to the underreporting

of injuries (concussions in particular), and differences between the leagues, including scheduling,

electronic medical record systems, and injury definitions.

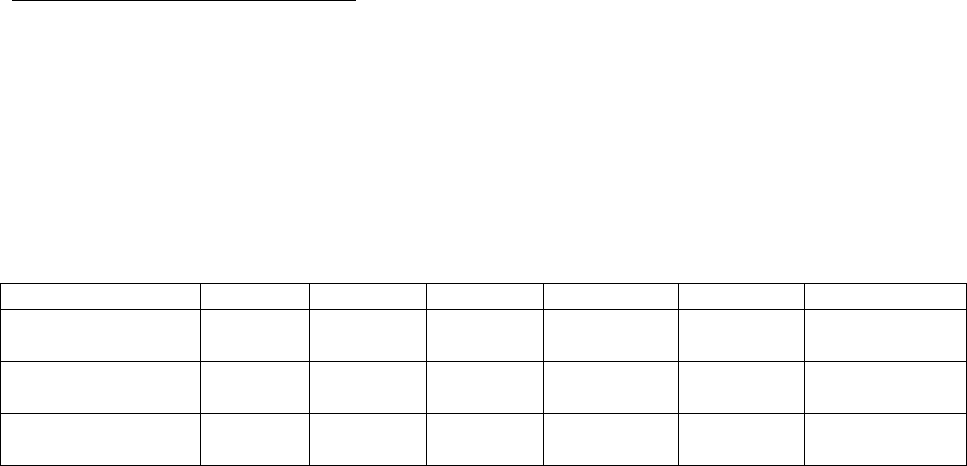

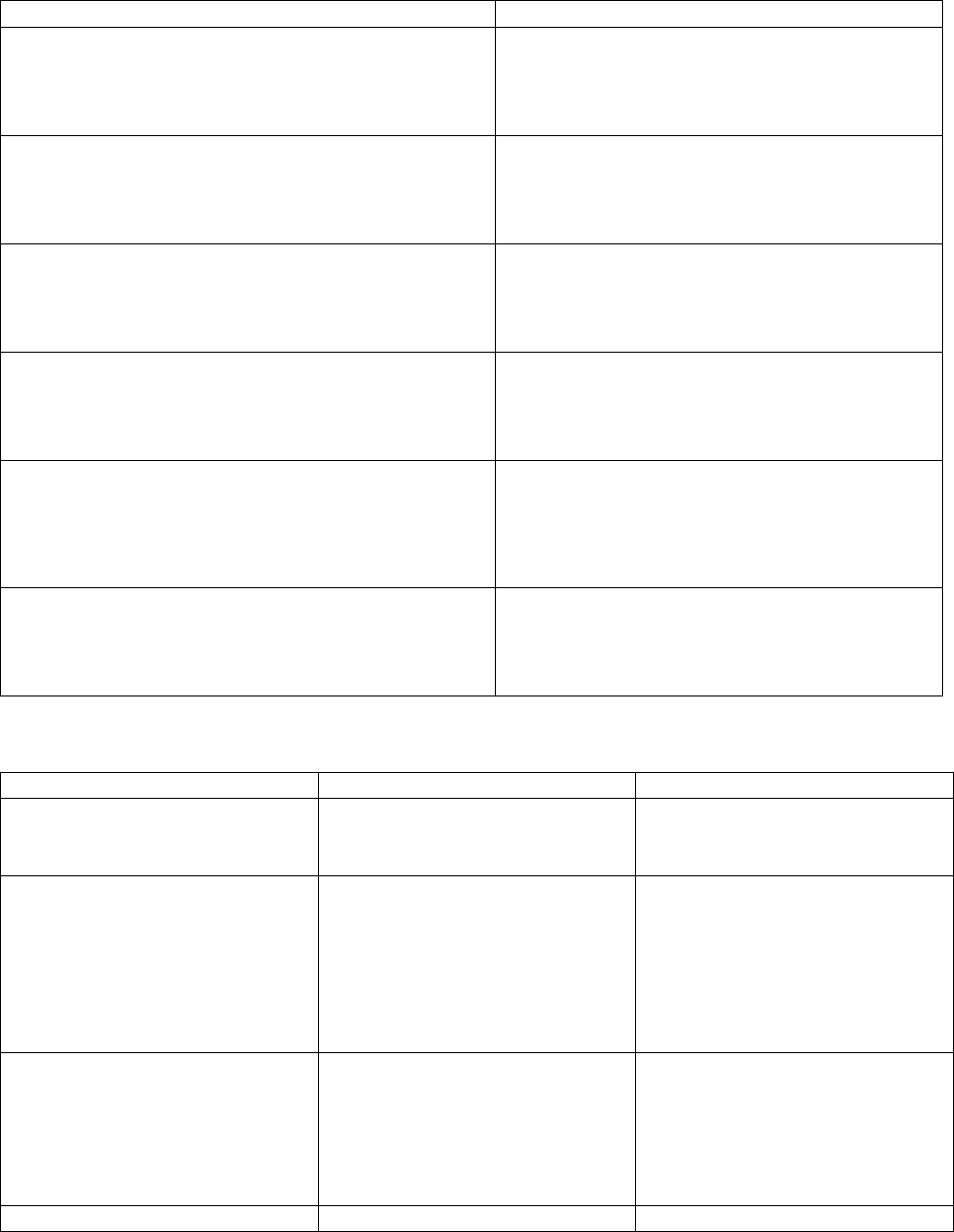

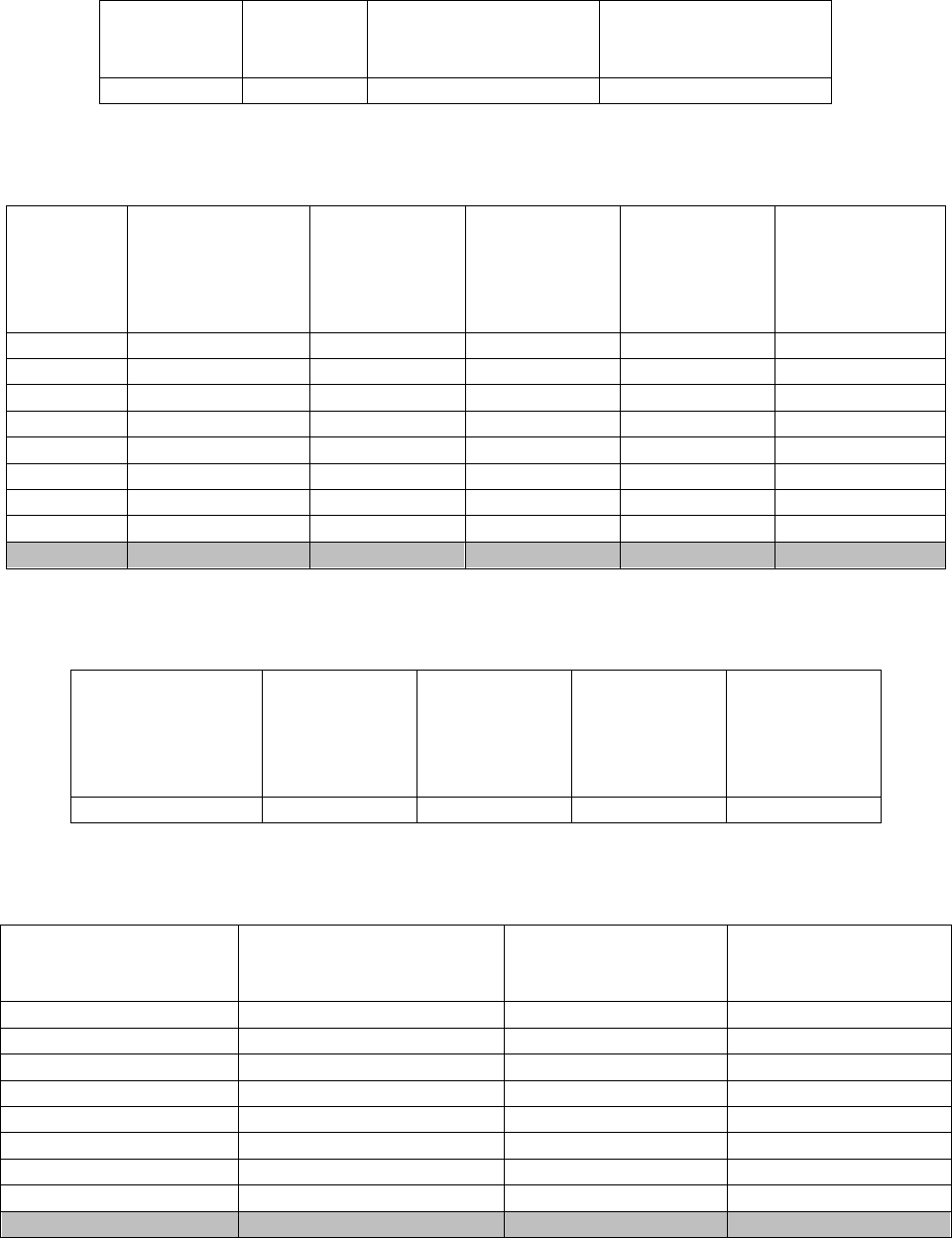

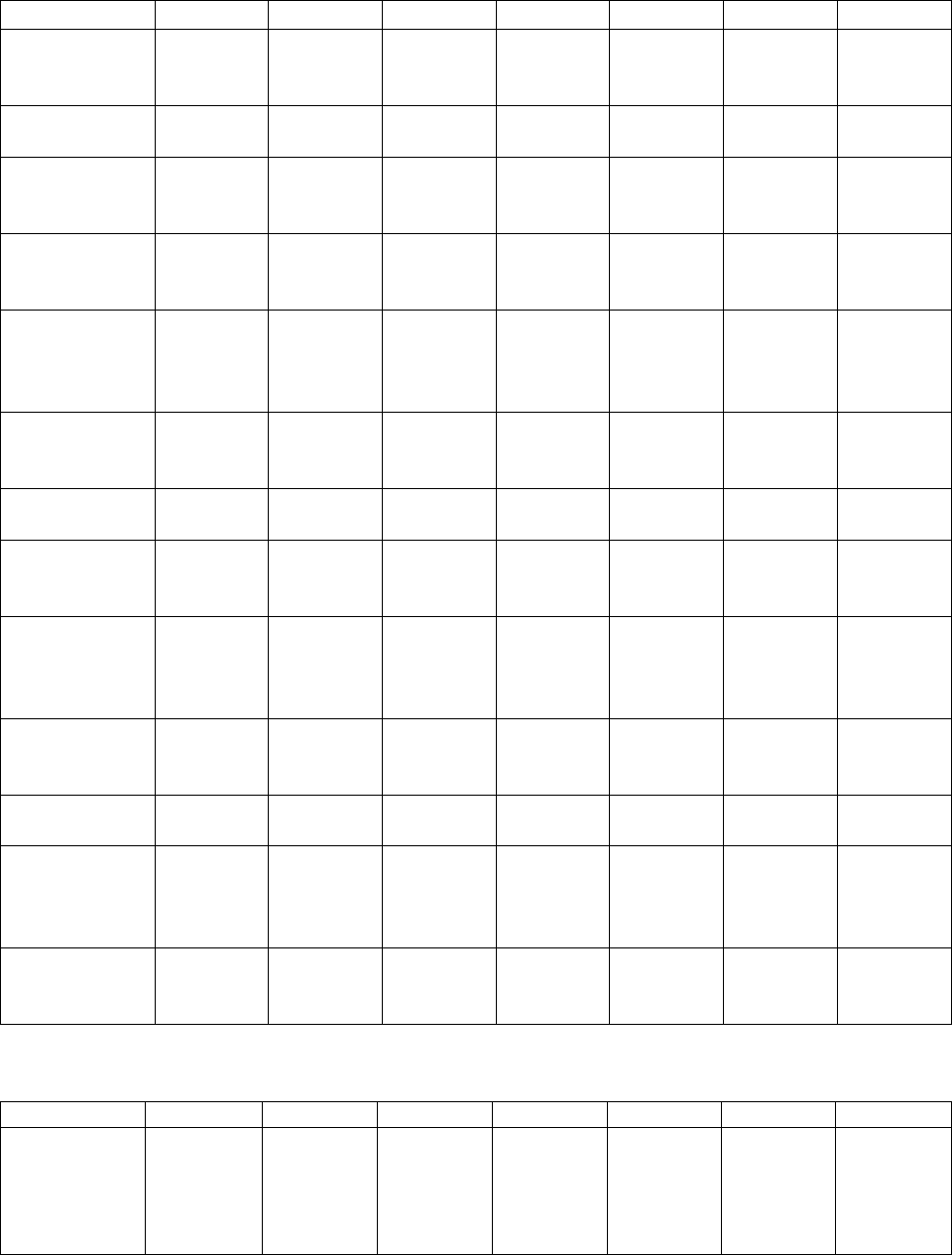

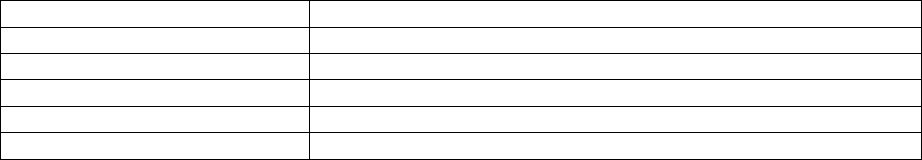

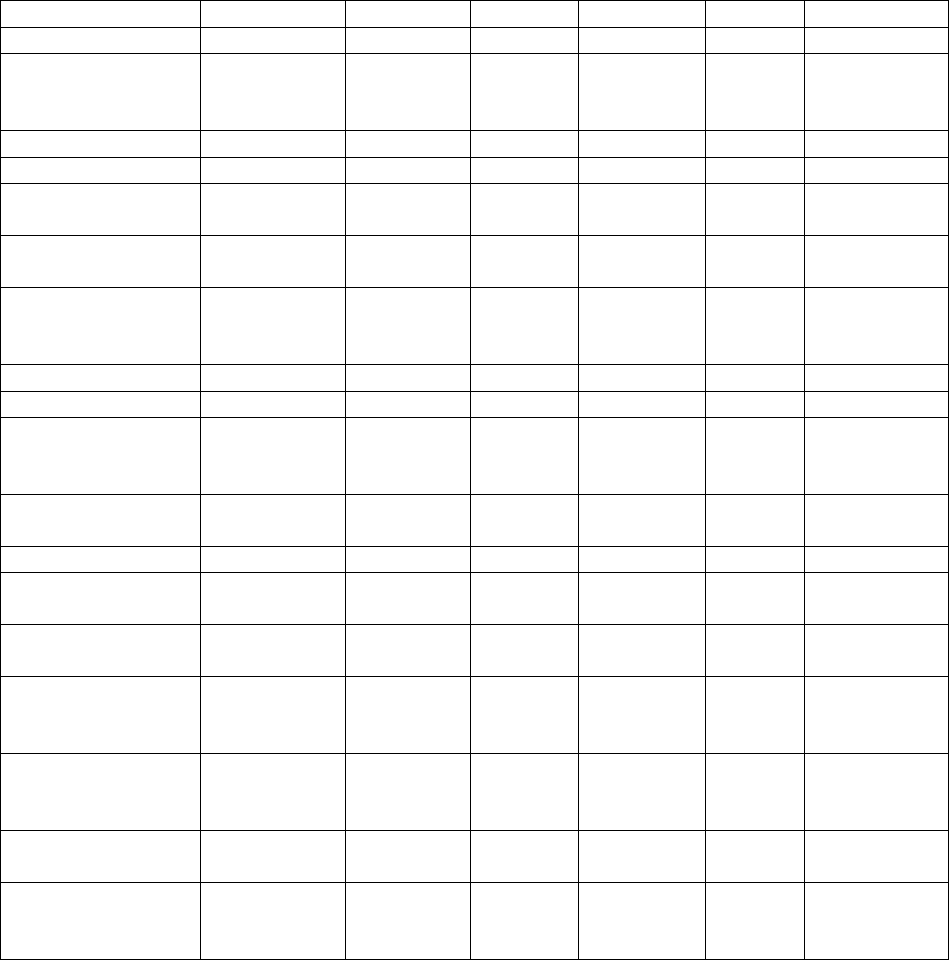

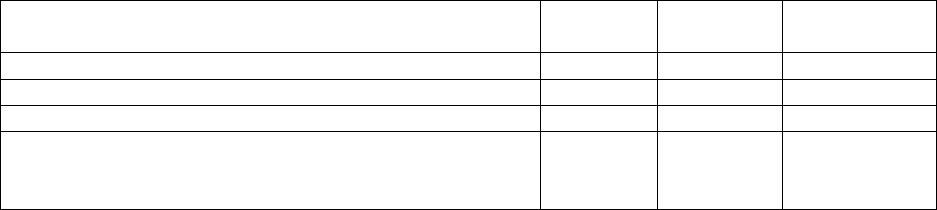

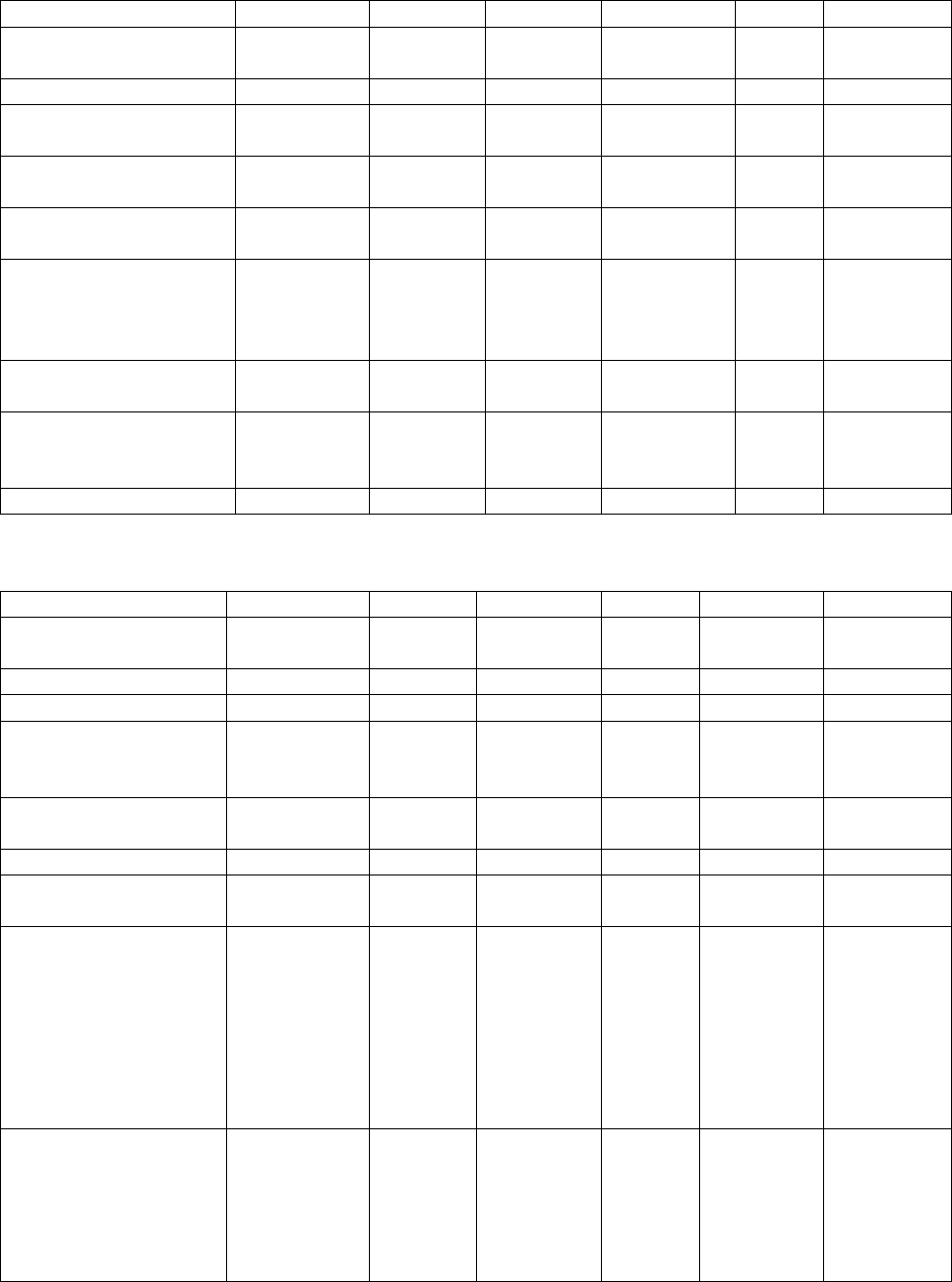

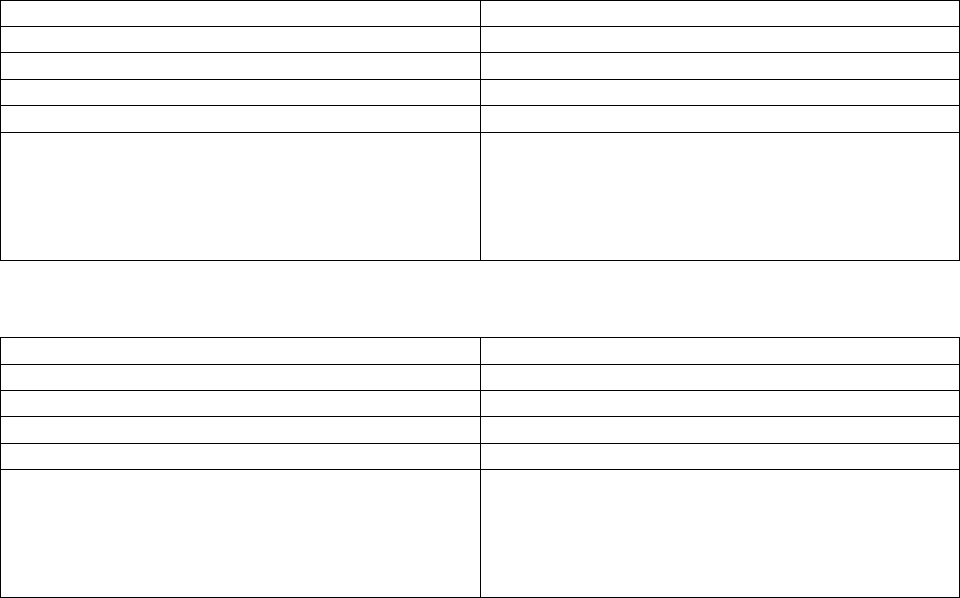

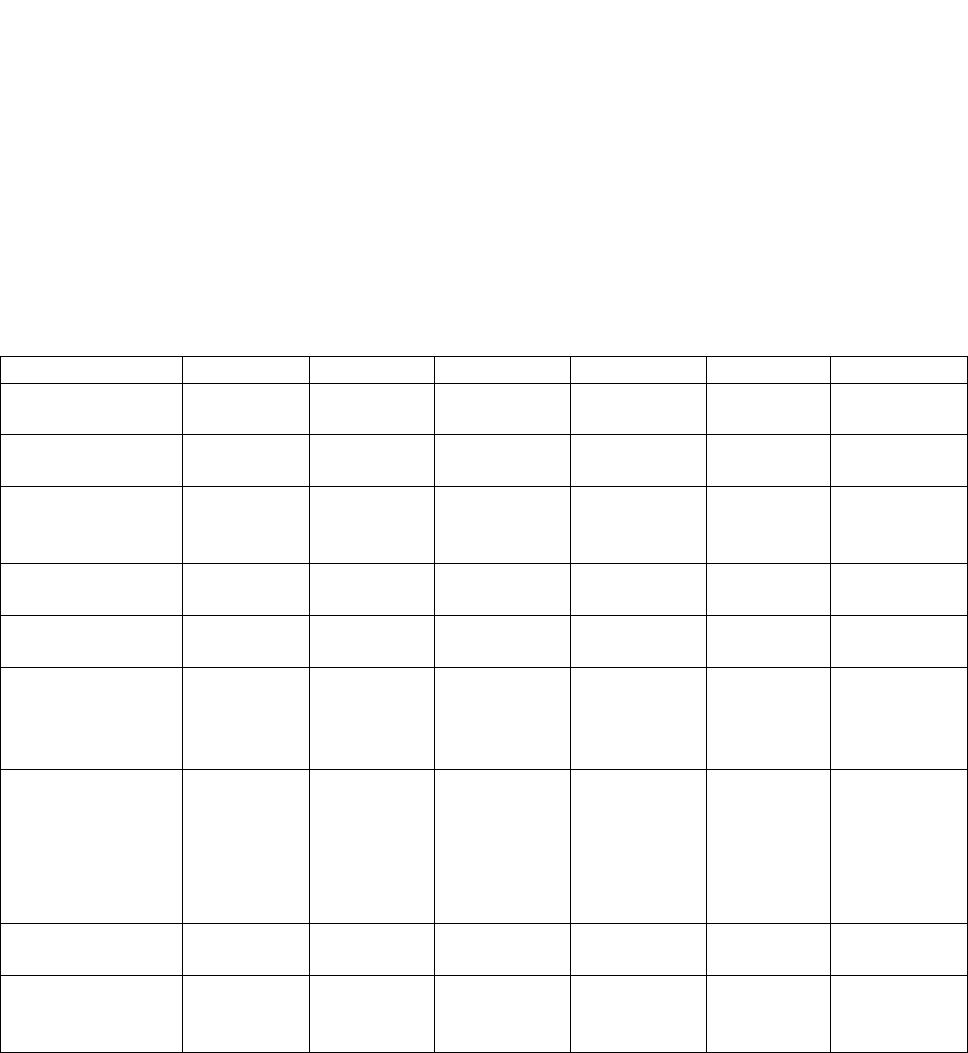

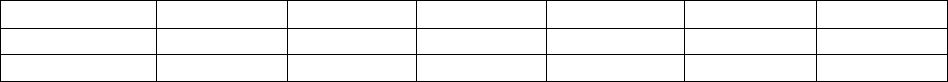

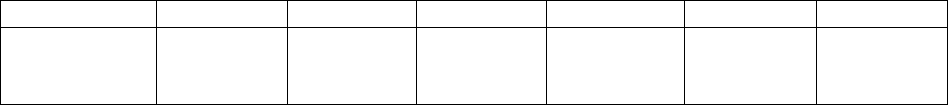

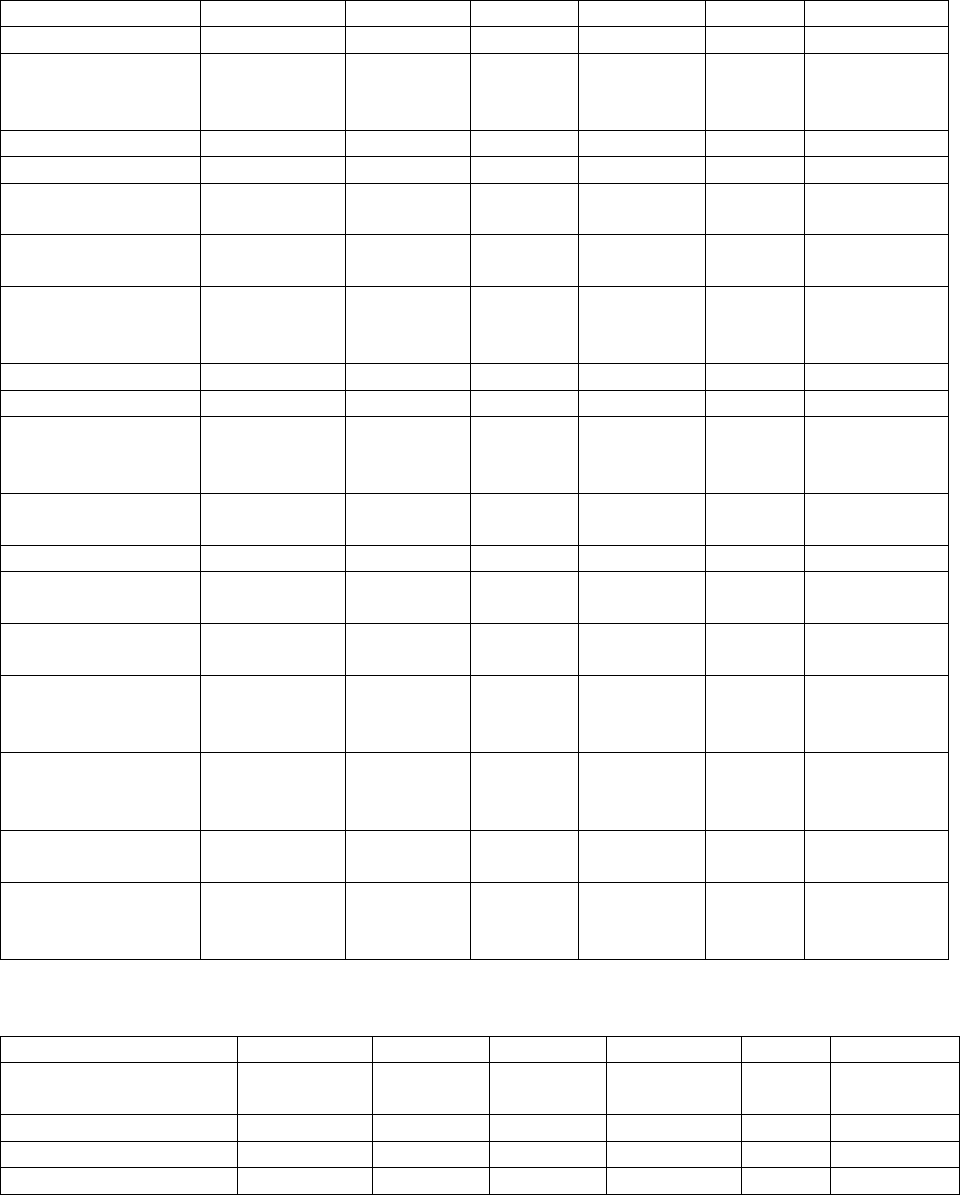

Statistic

NFL

MLB

NBA

NHL

CFL

4

UEFA

5

Mean Injuries Per

Game

5.90

0.45

0.16

0.59

N/A

0.53

Concussions Per

Game

0.625

0.007

0.007

0.067

0.704

0.010

Rate of Concussion

Per Player-Game

6

0.00679

0.00026

0.00035

0.00180

0.00800

0.00072

This Table provides some of the key injury statistics in comparing the leagues, though we provide many

more statistics and caveats in the Report itself. The NFL’s injury rates are much higher than those of the

other leagues. The mean number of injuries suffered per game in the NFL is approximately 3.4 times

higher than the combined rates of MLB, the NBA, NHL, and UEFA combined. Similarly, the NFL’s

concussion per game rate is approximately 6.9 times higher than the combined rates of those same

leagues. We excluded the CFL from this comparison because it is also a football league, but we note that

the CFL’s concussion per game rate is actually higher than the NFL’s.

At the same time, the NFL’s rate of concussions per player-season is 0.073, lower than the NHL’s of

0.108. Thus, if one compared one NFL player and one NHL player, the NHL player would be more likely

to suffer a concussion in his next regular season than the NFL player during his next season. However,

this difference is due to the fact that the NHL plays substantially more regular season games than the NFL

(82 versus 16). When comparing concussion statistics on a per game basis, an NFL player is

approximately 3.8 times more likely to suffer a concussion in a regular season game as compared to an

NHL player (0.00679/0.00180).

One other caveat is worth emphasizing. Due to data availability these statistics and those in the Report are

limited to the leagues’ regular season games, which underestimates injury rates. As we emphasize in the

full Report, there are a significant number of injuries and concussions sustained during NFL practices and

during the pre-season (90 concussions in 2015 practices and pre-season games).

Injury Tracking Systems

!

18!

Each of the Big Four leagues and the MLS has an injury tracking system of some kind. Discussions with

experts on this issue indicated that the injury tracking systems are generally comparable; each of them is a

sophisticated and modern system that should enable accurate reporting and provide interesting and useful

data. The differences may come in how the leagues use the data that is available to them.

The NFL and NBA employ Quintiles, a health information technology firm, to perform sophisticated data

analysis concerning player injuries. While other leagues have occasionally made injury data available for

analysis, our research has not revealed whether the other leagues perform an ongoing annual analysis like

Quintiles does for the NFL and NBA.

Injury-Related Lists

The NFL, NBA, and NHL all permit their clubs to declare players inactive one game at a time, which is

generally advantageous to players. We use the NFL as an example. In the NFL, clubs have a 53-man

Active/Inactive List, only 46 of whom can be active for the game each week. The remaining seven

players are placed on the Inactive List for the game, i.e., benched, either for injury or skill purposes, but

are available to play in the next week’s game. This arrangement permits players the opportunity to remain

on the roster but to rest and treat an injury without immediately rushing back to play. At the same time,

because clubs are constantly struggling with having the best players available as well as likely having

multiple injured players, players will still likely feel pressure to return as soon as possible so that the club

can deactivate other injured players and avoid seeking a replacement.

The Active/Inactive List is also interrelated with the Injured Reserve list, designated for players with

longer-term injuries. Generally, once a player is on Injured Reserve, he is no longer eligible to play that

season. However, by placing the player on Injured Reserve, the club can replace the player on the 53-man

Active/Inactive List. Thus, there are important implications in determining whether the player’s injury is

short-term and the club only has to declare him inactive for a game or two, or whether the player’s injury

is more severe and requires the player to be placed on Injured Reserve (which also allows the club to

obtain a replacement player to join the 53-man roster).

The interplay between the short-term Inactive List and the longer term Injured Reserve list is particularly

important concerning concussions. As discussed in the full Report, concussions present uncertain

recovery times, are challenging to diagnose and treat, and present particularly acute long-term concerns.

MLB is the only sport with a concussion-specific injured list. Because of these concussion-specific

concerns, we recommend that the NFL also adopt a concussion-specific injured list.

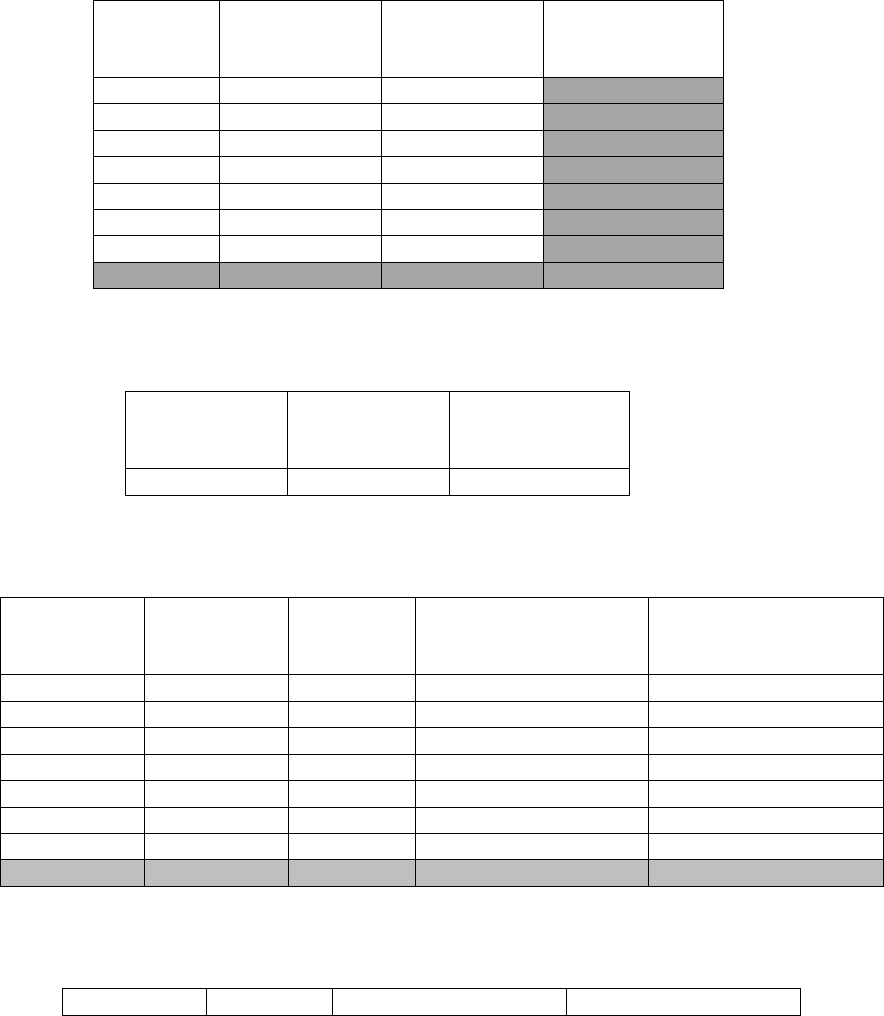

Injury Reporting Policies

There are three variations in the leagues’ injury reporting policies.

First, the NFL, NBA, NHL, and MLS require clubs to disclose publicly players’ injury statuses.

Second, the NFL, NBA, and MLS require clubs to disclose publicly the nature of player injuries. While

the NHL requires clubs to disclose whether a player will miss a game or not return to a game due to

injury, the NFL and NBA (in practice) require that the club identify the player’s body part that is injured.

Below, we make a recommendation concerning this issue.

Third, in MLB, the NBA, the NHL, and MLS, the CBAs specifically describe what type of information

the clubs are permitted to disclose publicly. The NFL CBA is silent on this issue. Instead, NFL clubs

seemingly rely on players’ to execute waivers providing the clubs with permission to disclose publicly

player health information.

!

19!

In the full Report, we discuss in detail three concerns related to the NFL’s Injury Reporting Policy: (1) a

general concern about an individual’s medical information being made publicly available; (2) the

possibility that players will target other players’ injuries that have been publicly disclosed; and, (3) the

Injury Reporting Policy’s role in preventing gamblers from receiving inside information about player

health issues. Ultimately, we believe that it is debatable whether the NFL’s gambling-related concerns

are sufficiently substantial today to justify overriding a player’s right to have his health information

treated confidentially. We lack the relevant expertise, insight, and information, however, to recommend

that the NFL no longer obligate clubs to report information on the status of players. Instead, we

recommend the NFL consider the issue more closely, in addition to other injury-related issues:

• Recommendation 2-A: The NFL, and to the extent possible, the NFLPA, should: (a)

continue to improve its robust collection of aggregate injury data; (b) continue to have the

injury data analyzed by qualified professionals; and, (c) make the data publicly available

for re-analysis.

• Recommendation 2-B: Players diagnosed with a concussion should be placed on a short-

term injured reserve list whereby the player does not count against the Active/Inactive 53

man roster until he is cleared to play by the NFL’s Protocols Regarding Diagnosis and

Management of Concussions.

• Recommendation 2-C: The NFL should consider removing the requirement that clubs

disclose the location on the body of a player’s injury from the Injury Reporting Policy.

Chapter 3: Health-Related Benefits

In this Chapter, we summarize the various health-related benefits available to the players in each of the

leagues. Specifically, for each league, we examine: (1) retirement benefits; (2) insurance benefits; (3)

disability benefits; (4) workers’ compensation benefits; (5) education-related benefits; and, (6) the

existence of health-specific committees jointly run by the league and players association. Each of these

domains is relevant to protecting players should they experience negative health effects during and after

their playing years, and also to promoting their ability to maintain their health and well-being over the

longer term. Given that a decision to play or continue to play professional sports, like many other

decisions, is a matter of weighing risks and benefits, those decisions must be made against a backdrop of

available benefits. It is for this reason that we spend considerable space describing and evaluating the

available benefits in each league.

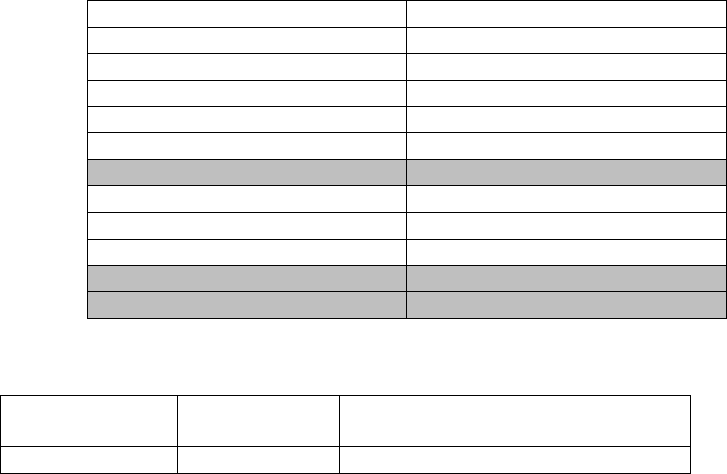

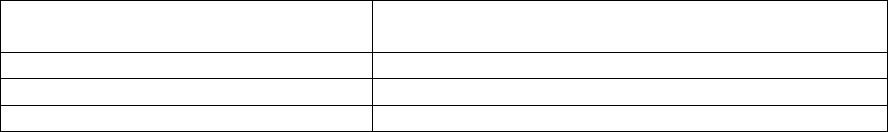

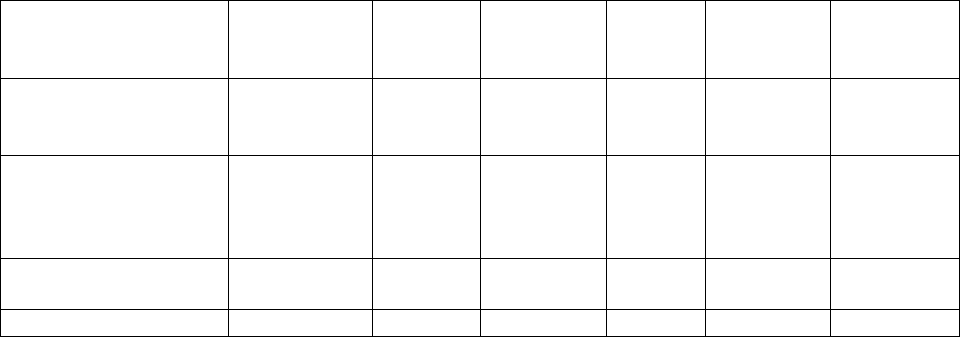

According to the NFLPA, NFL players have “the very best benefits package in professional sports.” This

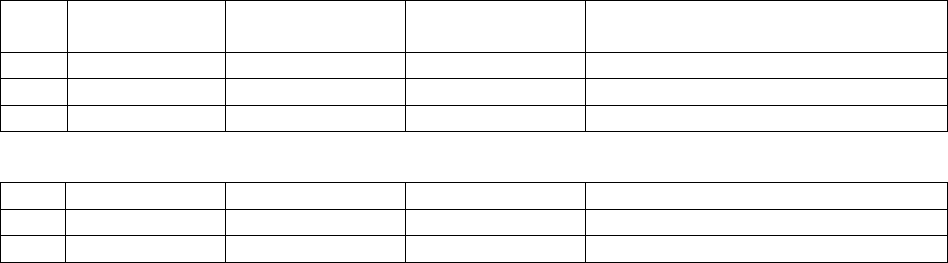

claim seems substantially true. First, the NFL offers every benefit that is provided by any of the other

leagues. Second, the NFL offers several benefits that are not provided by any of the other leagues,

including severance pay, long term care insurance, the Former Player Life Improvement Plan, and

neurocognitive disability benefits for former players. Third, there are several benefits that only the NFL

and a limited number of the other leagues provide: (a) only the NFL, MLB, NBA, and NHL provide

health insurance (beyond COBRA) for former players; (b) only the NFL, MLB, and NBA provide players

with mental health and substance abuse treatment; (c) only the NFL and NBA offer a health

reimbursement account; (d) only the NFL and MLB offer disability benefits to former players; (e) only

the NFL and NBA offer education-related benefits for all players; and, (f) only the NFL, NBA, NHL, and

MLS guarantee workers’ compensation benefits to all of their players.

7

!

20!

While overall the NFL thus appears to be the best league for benefits, there are, however, three areas in

which the NFL might appear deficient as compared to one or more of the other leagues.

First, the NFL’s health insurance options for former players appear to be less favorable than those offered

by MLB, the NBA and the NHL. Currently, for players who have vested under the Retirement Plan

(which requires at least three years of Credited Service for players after 1992), the NFL provides the same

health insurance as available to current players for five additional years or the former player can also

obtain health insurance via COBRA. However, COBRA is designed to be a temporary solution and is

generally regarded as expensive relative to other health insurance plans. In contrast, MLB’s Benefit Plan

provides former players the option to continue (or obtain) the same health insurance benefits as current

players for life. While former MLB players have to pay more for their health insurance than current MLB

players, presumably the plans offered are cheaper than COBRA coverage or players would select that

option. Similarly, the NBA’s Retiree Medical Plan is available to former players for life (at varying rates)

and the NHL allows former players who played at least 160 games to continue with the NHL’s insurance

plan for life.

The NFL does offer a variety of health benefits that might partially fill the gap for former players,

including health reimbursement accounts, long term care insurance, benefits for uninsured former players,

and disability benefits. Nevertheless, players often have to go through a difficult process to obtain some

of these benefits after they have already had to pay for the care, or care is delayed until they can obtain

the benefits. We suggest that there may be advantages to allowing former players to continue to obtain

some form of the health insurance that they were able to receive while playing.

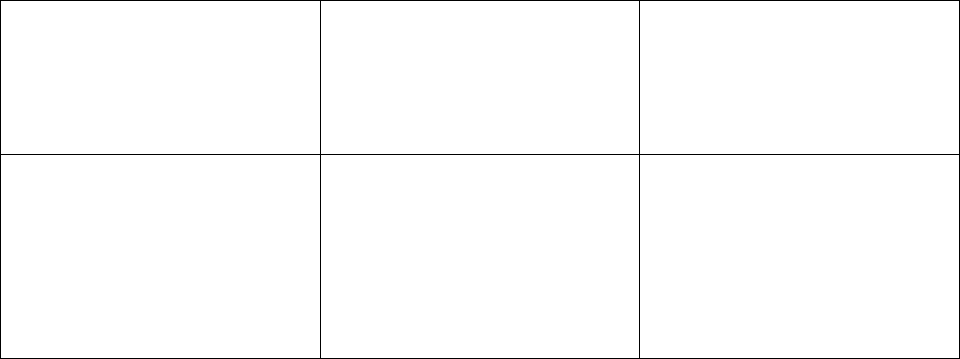

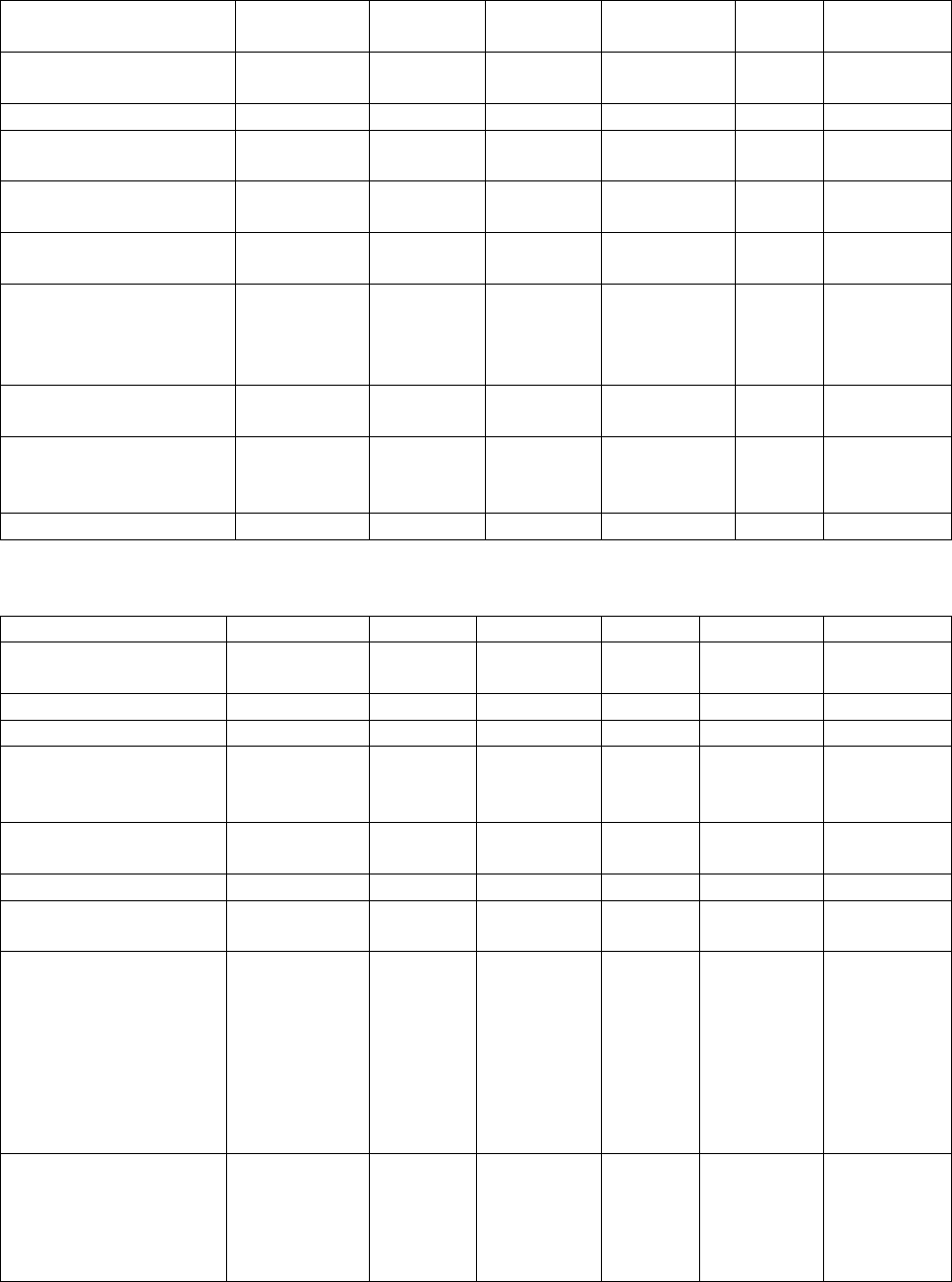

Second, as shown in the full Report (Tables 3-J and 3-K) the monthly payments to former NFL players

under the Retirement Plan are seemingly the smallest in the Big Four leagues. Nevertheless, when all of

the benefits available to former players are packaged together, it is likely that the NFL’s benefits are the

most valuable due to the number of benefits that are available. Consequently, lower Retirement Plan

payments might simply reflect the NFLPA’s preferred allocation of total benefits, i.e., a shifting of the

value of benefits away from the Retirement Plan and to other benefits instead. As with health insurance

benefits, the NFL’s Retirement Plan payments require players to undertake relatively little administrative

work to receive benefits and they are a more secure and stable income source and benefit than some of the

other benefits made available by the NFL. Nevertheless, some might believe it is a better use of player

benefit money to fund benefits and programs for former players who are disabled or impaired in some

way as opposed to providing larger Retirement Plan payments to all eligible former players. All of the

benefits available to NFL players must be viewed collectively. For these reasons, we recommend the NFL

and NFLPA consider whether the current allocation of player benefits is the preferred, most just, and most

effective allocation.

Third, MLB and NHL players are vested in their pension plans on the first day they play in those leagues.

By comparison, the NFL requires players to accrue three years of experience (or more depending on when

they played), before they are eligible for retirement benefits (as well as many other benefits). The mean

career of NFL and MLB players are both around five years long. Yet, the NFL’s Retirement Plan likely

excludes and has excluded thousands of former players who did not earn three Credited Seasons. It is

unclear why the NFL requires three years of service (the NBA does as well). The minimum service time

clearly reduces costs for the Retirement Plan, but might also reflect a policy decision as to when an NFL

player has sufficiently contributed to the NFL to deserve pay under the Retirement Plan. Below, we make

a recommendation concerning the vesting requirement for the NFL’s Retirement Plan:

• Recommendation 3-A: The NFL and NFLPA should consider whether change is necessary

concerning player benefit plans.

!

21!

o The NFL and NFLPA should consider providing former players with health insurance options

that meet the needs of the former player population for life.

o The NFL and NFLPA should consider increasing the amounts available to former players

under the Retirement Plan.

o The NFL and NFLPA should consider reducing the vesting requirement for the Retirement

Plan.

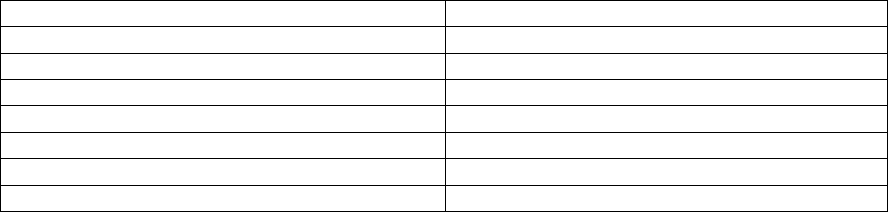

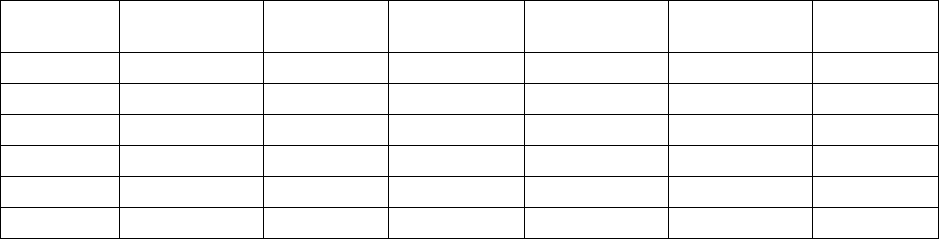

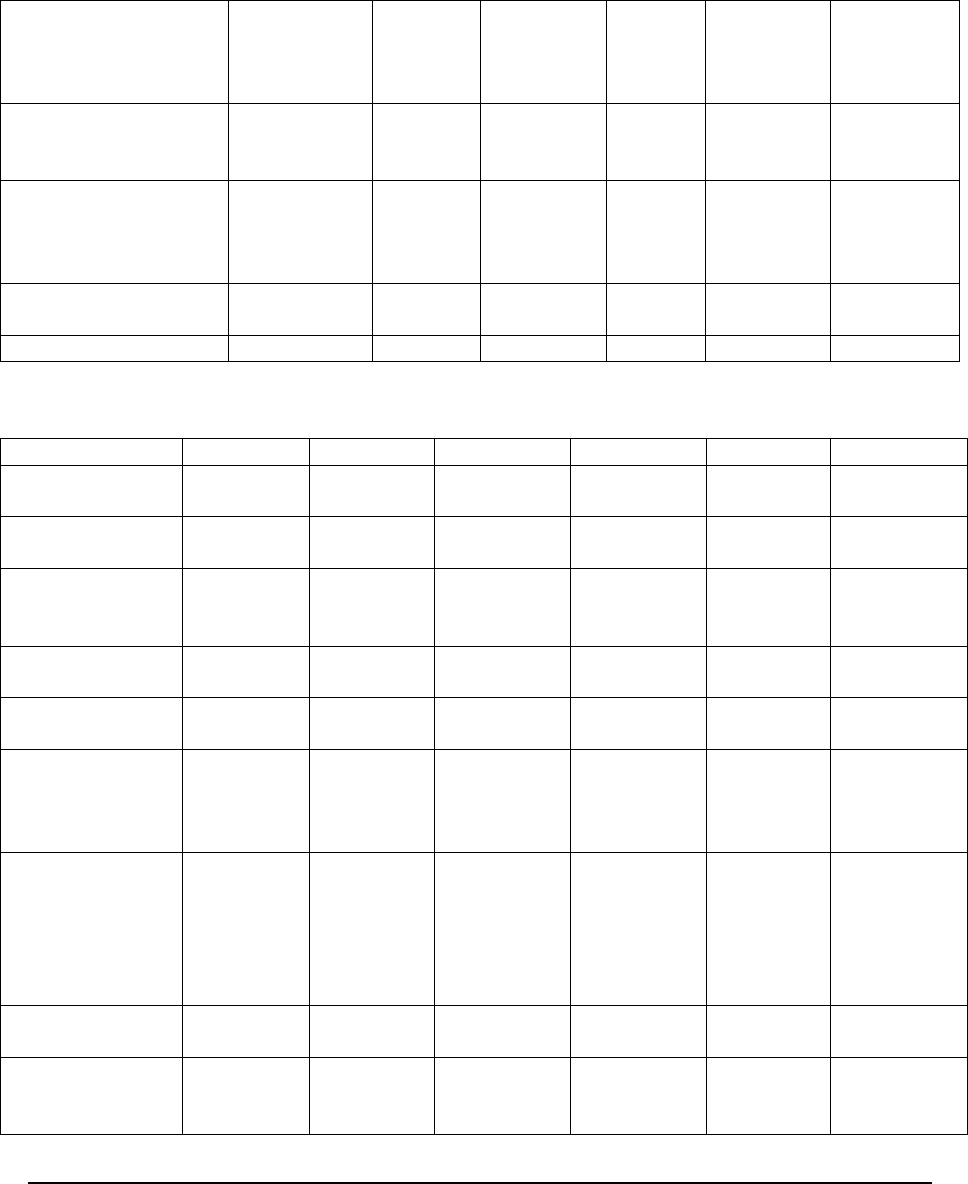

Chapter 4: Drug and Performance-Enhancing Substance Policies

This Chapter summarizes the policies of each of the leagues concerning performance-enhancing

substances (“PES”) and drugs of abuse. As explained below, the leagues differ at times in their

categorizations and treatments of different drugs and substances. Where appropriate, we will separate our

analysis of the leagues’ policies by PES and drugs of abuse (collectively “drug policies.”) The leagues’

definitions are discussed at length in the full Report.

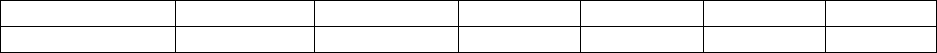

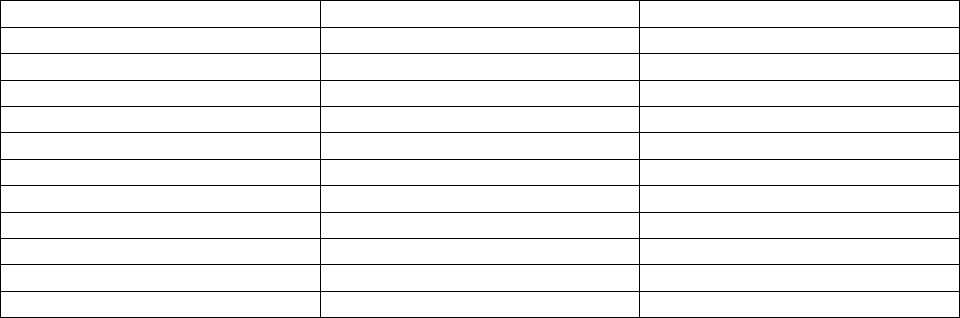

With the possible exception of how marijuana is regulated, the Big Four’s drug policies do not vary

substantially. Leagues and unions balance multiple factors in creating drug policies, including but not

limited to deterrence, treatment, privacy, and integrity of the game, and rely on difficult value judgments.

The three features of the policies we view as most important to player health and those which we analyze

are: (1) the availability of Therapeutic Use Exemptions (“TUEs”); (2) the availability of treatment; and,

(3) the opportunity to receive treatment without being subject to initial discipline. With these issues in

mind, we turn to our analysis of how the NFL compares to the other leagues.

Concerning TUEs, the NFL, MLB and the NBA all offer TUEs for both their PES and drugs of abuse

policies. In contrast, the CFL offers TUEs for its PES policy but does not have a drugs of abuse policy.

We also found no evidence that the NHL offers a TUE for its Substance Abuse Program or that the MLS

offers any TUEs. Thus, the NFL’s use of TUEs is at least as good as the other leagues.

All of the leagues, including the NFL, have robust treatment programs for drugs of abuse. However, the

NBA, CFL, and potentially MLS are the only leagues that offer treatment for a player who has violated a

PES Policy. On this issue, the NFL might appear deficient compared to the NBA and CFL. However,

there are other relevant considerations concerning the treatment programs offered to players, discussed

next.

The NFL, NBA, NHL, MLS and maybe MLB provide a safe-harbor for players who voluntarily refer

themselves for treatment for drugs of abuse. These provisions importantly allow players to seek help they

might recognize they need without the fear of immediate adverse employment action.

In contrast, no Big Four league offers a safe-harbor for players who have used PES. It is possible that

these leagues view PES users as players intentionally looking to cheat the game and their competitors,

whereas those using drugs of abuse are in need of medical care. However, there is robust scientific

evidence supporting the need to provide treatment to PES users, as well. PES usage has shown to be

addictive, and has been associated with the use of drugs of abuse (opioids in particular), body dysmorphic

disorder, depression, antisocial traits, mood and personality disorders, other psychological disorders, and

cognitive deficits in impulsivity, risk-taking, and decision-making. As a result, PES users may experience

withdrawal symptoms, and may be at an increased risk of suicide. Consequently, many experts

recommend and provide treatment and counseling for PES users. We adopt that recommendation for

purposes of this Report:

!

22!

• Recommendation 4-A: The NFL should consider amending the PES Policy to provide

treatment to any NFL player found to have violated the PES Policy.

Chapter 5: Compensation