Volume 2 • Issue 6 • 1000117

J Sports Med Doping Stud

ISSN: 2161-0673 JSMDS, an open access journal

Tran, J Sports Med Doping Stud 2012, 2:6

DOI: 10.4172/2161-0673.1000117

Research Article Open Access

Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors across 50 States in the

U.S.

Xuan Tran*

University of West Florida, USA

Abstract

Despite the growing evidence of role personality plays on sport and exercise related behavior, little is known about

the inuence of personality traits on football players in the U.S. The purpose of this study was to explore the effects

of the big ve personality traits on football achievements. Extraversion (E), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness

(C), Neuroticism (N), and Openness (O) traits obtained from 619,397 U.S. respondents in a previous study were used

as predictors to state-level football scores in this study. Across 50 states in the U.S., football ranks were positively

correlated with state scores on the Big Five personality factors of conscientiousness and agreeableness. However,

when applying multiple regression analyses to the prediction model for football ranks based on ve independent

variables of the Big Five personality factors, only conscientiousness and neuroticism would signicantly predict

football ranks. Agreeableness correlates with football ranks but does not contribute to the prediction model since

agreeableness is collinear with conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness. Neuroticism insignicantly correlates

with football ranks but contributes to the prediction because the suppressor effect of conscientiousness by neuroticism

has improved its predictor of football ranks. The ndings implied that in order to increase high ranks in football practice,

selection for athletics would focus on persons with high conscientiousness and neuroticism.

*Corresponding author: Xuan Tran, University of West Florida, USA, E-mail:

Received September 22, 2012; Accepted October 26, 2012; Published October

26, 2012

Citation: Tran X (2012) Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors

across 50 States in the U.S. J Sports Med Doping Stud 2:117. doi:10.4172/2161-

0673.1000117

Copyright: © 2012 Tran X. This is an open-access article distributed under the

terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and

source are credited.

Keywords: Conscientiousness; Neuroticism; Extroversion; Agree-

ableness; Openness; Football

Introduction

Personality can be dened as the intrinsic organization of an

individual’s mental world that is stable over time and consistent over

situations [1]. e importance of personality as a predictor for behavior

performance has been recognized in psychology [2]. Researchers have

recently reported the signicant eects of personality on sports [3].

What personality type of person is the successful athlete playing

football? Are the athletes’ personality traits related to their performance

on the football eld? Using the Prole of Mood States [4-6] had dierent

answers to these questions. It has been reported that no unifying theory

of personality and no consensus about which personality dimensions

to measure or how to measure them, comparisons of personality were

dicult to interpret and, arguably, unreliable [7].

Contemporary research uses the Big Five personality factor

model (Extraversion (E), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness

(C), Neuroticism (N), and Openness (O)) as a reliable and valid

measurement for psychological characteristics [8] based on the three

main reasons. First, the ve dimensions are rooted in biology [9].

Second, the dimensions are relatively stable throughout life [10], and

third, the dimensions are found in several cultures [11].

Most research has focused on the eects of the ve personality

traits on human behavior. Agreeableness reects warmth, compassion,

cooperativeness, and friendliness. Agreeableness was negatively related

to rates of robbery, murder, and property crime [12]. Extraversion

is associated with sociability, energy, and health. Dierent from

agreeableness, extraversion reects sociability and outgoingness

more than friendliness and warmth [13]. Conscientiousness reects

dutifulness, responsibility, and self-discipline. Low-conscientiousness

individuals are more likely to commit acts of violence and deviance

than are high-conscientiousness individuals [12]. Neuroticism reects

anxiety, stress, impulsivity, and emotional instability and is related

to antisocial behavior, poor coping, and poor health [12]. Openness

reects curiosity, intellect, and creativity. Open individuals prefer jobs

that involve a high degree of abstract and creative thought [12].

Little contemporary research has explored the eects of the ve

personality traits on football although football is one of the key sports

in the United States. is research attempted to explore the inuence of

football players’ personality traits on their achievements. e purpose of

this study was thus to examine the eects of neuroticism, extraversion,

openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness on football ranks

across 50 states to propose the most eective way to develop a successful

football team based on personality traits.

Literature

Some studies have specically examined the role of the Big Five in

predicting academic performance [14]. Studies have also indicated a

positive relationship between conscientiousness and job performance

[15]. Piedmont et al. [16] examined the coaches’ ratings on their games

and found that there were signicant correlations between athletic

ability and personality. Kovacs [17] reported that conscientiousness

and neuroticism have a direct correlation to athletic performance.

Extraversion has been found to predict sport performance, particularly

in team athletes [18]. Aidman and Schoeld [3] reported that

Agreeableness and Openness are not correlated with sport performance.

e present study has focused on the ve personality traits at state

level based on the assumption that psychological characteristics are

geographically clustered across the country. ere are at least three main

reasons for geographic variations on personality across 50 states in the

United States. First, the early child rearing practices form psychological

characteristics and these practices are shaped by larger societal

institutions in which individual lives [19]. Secondly, in the United States

the groups of immigrants who chose to leave their homeland possess

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

S

p

o

r

t

s

M

e

d

i

c

i

n

e

&

D

o

p

i

n

g

S

t

u

d

i

e

s

ISSN: 2161-0673

Journal of Sports Medicine & Doping

Studies

Volume 2 • Issue 6 • 1000117

J Sports Med Doping Stud

ISSN: 2161-0673 JSMDS, an open access journal

Citation: Tran X (2012) Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors across 50 States in the U.S. J Sports Med Doping Stud 2:117.

doi:10.4172/2161-0673.1000117

Page 2 of 5

restricted gene pools of nonrandom samples of personality traits [20].

Finally, there appear geographic variations on personality because the

specic personality of social founders may inuence regional people’s

personality traits [21]. Rentfrow et al. [20] examined big ve personality

traits from over half a million U.S. residents and found that (1) North

Dakota was ranked as the state with highest extroversion but Maryland

as the state with lowest extroversion; (2) North Dakota was again

ranked as the state with the highest agreeableness but Alaska as the state

with lowest agreeableness; (3) New Mexico was ranked as the state with

the highest conscientiousness but Alaska as the state with the lowest

conscientiousness; (4) West Virginia was ranked as the state with the

highest neuroticism but Utah as the state with the lowest neuroticism;

(5) Washington, D.C. as the district with highest openness but North

Dakota as the state with the lowest openness. As a result, y U.S. states

possessed dierent levels of big ve personality traits [20].

When 50 states are dierentiated by their own personality,

they will inuence athletic performance since the ve personality

factors (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and

agreeableness) reect the core aspects of humans in the sport domain.

erefore, this study hypothesized that there would be signicant

relationship between football ranks and the big ve personality factors

across 50 states.

Methods

Ethical clearance

According to Rentfrow et al. [20], the personality data were

collected as part of an ongoing study of personality involving volunteers

assessed over the World Wide Web. e website is a noncommercial,

advertisement-free website containing a variety of personality

measures. Potential respondents could nd out about the site through

several channels, including search engines, or unsolicited links on

other websites. e data reported in the present research were collected

between December 1999 and January 2005. Respondents volunteered

to participate in the study by clicking on the personality test icon; they

were then presented with a series of questions about their personalities,

demographic characteristics, and state of residence. Aer responding to

each item and submitting their responses, participants were presented

with a customized personality evaluation based on their responses to

all the items [20].

Study design

e present study explored a model of the relationships between the

state-level ve personality factors and the state-level football scores. e

independent variables are state ranks for each personality dimension,

adapted from Rentfrow et al. [20]. e dependent variable is the state

ranks for football scores, adapted from Bleacher report [22].

Sampling

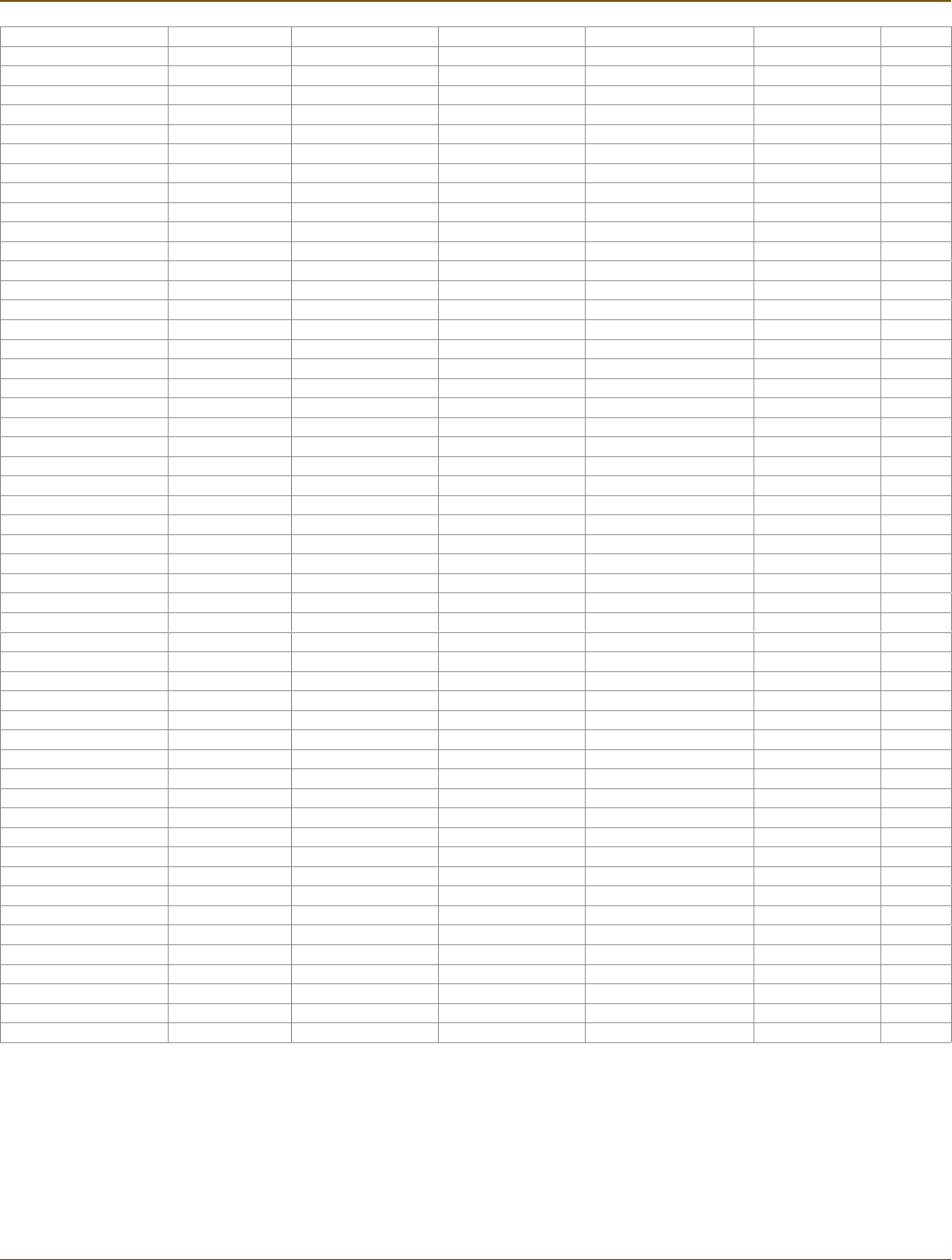

Table 1 provides 51 state ranks for each personality dimension and

football score, which were adapted from Rentfrow et al. [20] and the

Bleacher report [22].

According to Rentfrow et al. [20], in order to avoid the possibility

that respondents may complete a survey multiple times resulting in

unreliable and misleading results, the researchers used several criteria

to eliminate repeat responders. “First, one question included in the

survey asked: ‘‘Have you ever previously lled out this particular

questionnaire on this site?’’ If respondents reported completing the

questionnaire before, their data were excluded. Second, IP addresses

were used to identify repeat responders. If an IP address appeared two

or more times within a 1-hr period, all responses were deleted. ird,

if an IP address appeared more than once in a time span of more than

1 hour, consecutive responses from the same IP address were matched

on several demographic characteristics (gender, age, ethnicity etc.)

and eliminated if there was a match. Finally, only respondents who

indicated that they lived in the 50 U.S. states or in Washington D.C.

were included.” [20].

e sample size was 619,397 respondents (55% female). e median

age of respondents was 24 years (SD 59.8 years). e sample was

comprised of White (80.2%), African American (4%), Asian (6.6%),

Latino (4.6%), and other (4.6%). e respondents included social

class (13.5%), working class (15.6%), middle class (42.8%), and upper-

middle class (25.7%) and upper class (2.4%). Overall, these analyses

indicate that our Internet-based sample was generally representative of

the population at large [23].

Procedure-data collection and data analysis

Independent variables were extraversion, agreeableness, conscien-

tiousness, neuroticism, and openness. e ve personality traits were

obtained from e Big Five Inventory [13]. e Big Five Inventory con-

sists of 44 short statements designed to assess the prototypical traits

dening each of the ve factor model dimensions based on a 5-point

Likert-type rating scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree

strongly). e Big Five Inventory scales have shown reliability and va-

lidity compared with other ve factor model measures at the individual

level [24].

Dependent variable was state-level football scores ranked in order

for 50 states, which were available online from the Bleacher report [22].

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to nd the causative

relationship between football scores and ve personality traits.

Results

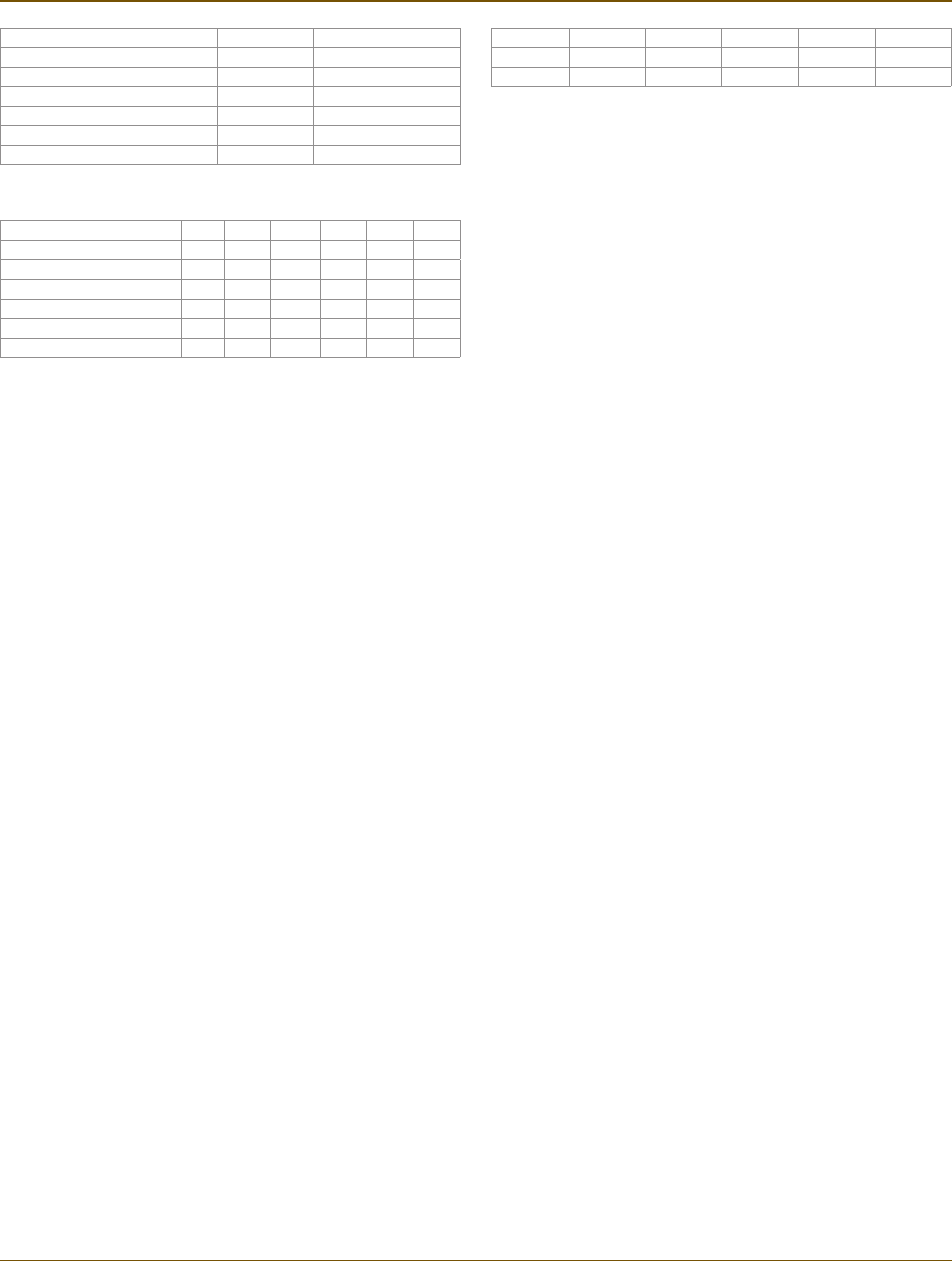

e means and standard deviations of the data were summarized

in table 2 as follows

Table 3 indicates that football ranks were positively associated

with scores on the Big Five Inventory factors of Agreeableness (r=.40,

two-tailed p=.003) and conscientiousness (r=.42, two-tailed p=.002)

but were not signicantly correlated to extraversion, neuroticism, and

openness (rs=.21, .11, and -.02, respectively). Using the Spearman rank-

order correlation coecient yielded similar results. Football ranks were

positively correlated with Agreeableness and Conscientiousness (rs=.40

and .43, two tailed ps<.001), but were not signicantly correlated

to Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Openness (rs=.20, .10, and -.01,

respectively).

Multiple regression analyses were used to test the causative

relationships between football ranks and ve personality traits

(Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and

Openness) as illustrated in table 4 as follows:

e result of the regression for football ranks indicated

conscientiousness and neuroticism explained 27% of the variance

(

R2=.27, F(5, 44)=3.29, p<.05). It was found that conscientiousness

and neuroticism predicted football rank (βs=.37 and .28, respectively,

ps<.05).

Discussions

Agreeableness correlates football rankings but does not contribute

to the prediction model since Agreeableness is collinear with

Conscientiousness, Extraversion, and Openness. Neuroticism does not

Volume 2 • Issue 6 • 1000117

J Sports Med Doping Stud

ISSN: 2161-0673 JSMDS, an open access journal

Citation: Tran X (2012) Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors across 50 States in the U.S. J Sports Med Doping Stud 2:117.

doi:10.4172/2161-0673.1000117

Page 3 of 5

correlate football rankings but contribute to the prediction because the

suppressor eect of Conscientiousness by Neuroticism has improved its

predictor of football rankings [25].

Like Kovacs’ [17] nding, there is an association between

conscientiousness and sport ranking. Conscientiousness is

signicantly positively correlated with football ranking. Moreover,

the present analysis indicated that conscientiousness would predict

football rankings. In addition, the study found the football rankings

were signicantly associated with neuroticism. A state with higher

neuroticism would get higher football rankings because neuroticism is

a strong predictor for football rankings. In sum, the signicance of these

relationships may contribute to selection and management of football

teams. It also helps forecasting the results of football competition

based on the prole of big ve personality traits. In order to increase

high ranks in football practice, selection for athletics would focus on

State Football Extraversion Agreeableness Conscientiousness Neuroticism Openness

Alabama 1 20 36 36 30 48

Alaska 42 49 51 51 47 49

Arizona 29 24 31 9 45 31

Arkansas 15 31 41 37 10 27

California 4 38 28 27 37 6

Colorado 32 28 29 15 50 8

Connecticut 38 33 43 46 15 12

Delaware 42 21 37 34 19 42

District of Columbia 42 3 50 40 31 1

Florida 2 10 14 8 36 13

Georgia 10 6 8 3 33 20

Hawaii 37 39 24 49 40 46

Idaho 22 46 39 26 32 30

Illinois 17 9 26 11 20 21

Indiana 8 34 19 14 13 34

Iowa 26 15 15 33 22 43

Kansas 31 13 17 5 34 38

Kentucky 27 36 21 19 7 45

Louisiana

9 30 13 30 8 29

Maine 42 11 46 50 12 35

Maryland 33 51 38 35 17 10

Massachusetts 34 42 40 43 11 4

Michigan 5 17 11 21 26 36

Minnesota 35 5 2 22 41 40

Mississippi 13 19 3 12 4 41

Missouri 25 18 16 10 25 32

Montana 42 43 42 29 39 16

Nebraska 11 4 10 7 44 44

Nevada 39 37 48 24 42 9

New Hampshire 42 50 30 44 14 14

New Jersey 36 14 34 45 5 15

New Mexico 41 22 33 1 29 23

New York 30 32 47 42 3 2

North Carolina 23 35 7 2 24 33

North Dakota 42 1 1 23 43 51

Ohio 6 25 27 38 9 24

Oklahoma 7 27 9 6 27 37

Oregon 21

44 18 31 48 3

Pennsylvania 14 12 35 28 6 25

Rhode Island 42 40 45 48 2 28

South Carolina 12 26 20 16 16 26

South Dakota 42 7 23 17 49 39

Tennessee 24 29 6 13 23 19

Texas 3 16 25 18 28 17

Utah 18 8 4 4 51 18

Vermont 42 47 12 41 18 7

Virginia 16 45 44 39 21 11

Washington 28 48 22 25 46 5

West Virginia 20 23 32 32 1 22

Wisconsin 19 2 5 20 35 47

Wyoming 40 41 49 47 38 50

Table 1: State Rankings for Each Five Factor Personality Dimension and Football Score. (Rentfrow et al. [20] and the Bleacher Report [22])

Volume 2 • Issue 6 • 1000117

J Sports Med Doping Stud

ISSN: 2161-0673 JSMDS, an open access journal

Citation: Tran X (2012) Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors across 50 States in the U.S. J Sports Med Doping Stud 2:117.

doi:10.4172/2161-0673.1000117

Page 4 of 5

persons with high Conscientiousness and Neuroticism. Future research

might also nd the model of these relationships useful when expanding

athletic departments.

Since low-Conscientiousness individuals are more likely to

commit acts of violence and deviance than are high-Conscientiousness

individuals [12], football players with low conscientiousness may be

likely to commit doping or other deviant behavior. Conscientiousness

reects the degree to which football players prefer systematic and

focused tasks and clearly dened rules and regulations so conscientious

individuals tend to engage in health promoting behavior and live

long healthy lives, which is consistent with previous research [26].

Conscientiousness was negatively related to spending time in a bar and

entertaining guests at home [20] so conscientious football players were

not related to social involvement. Rentfrow et al. [20] also reported that

large proportions of computer scientists and mathematicians in high

Conscientiousness states and more artists and entertainers are in low

Conscientiousness states.

Neuroticism reects anxiety, stress, impulsivity, and emotional

instability. Table 4 indicates that Neuroticism is a signicant predictor

in the model although the correlation between Neuroticism and

Football scores is not signicant. e reason for this is Neuroticism

is a suppressor. According to Cohen et al. [25], a suppressor that

is uncorrelated with Y may be signicant in a multiple regression

model. e suppressor eect of Conscientiousness by Neuroticism

has improved its predictor of football rankings. A football player with

high Neuroticism may take a risk to attain the goal by doping or anti-

social behavior; however, the direction of these relationships changed

when controlling for urbanization and income [20]. e research

showing inverse relationships between Neuroticism and longevity and

Neuroticism is negatively related social involvement [12,27].

Agreeableness reects warmth, compassion, cooperativeness, and

friendliness at the individual level. Agreeableness was correlated with

football scores but it did not predict football scores since football players

with high agreeableness were positively associated with activities that

promote tight social relations so it correlates with the football scores

when the players help others in their team but in order to attain the

goal, the cooperativeness should be replaced by competition.

An increase in conscientiousness is associated with an increase

in football ranking. Moreover, the present analysis indicated that

conscientiousness would predict football ranks. In addition, the study

found the football ranks were signicantly associated with neuroticism.

A state with higher neuroticism would get higher football ranks and

neuroticism is a strong predictor for football ranking. In sum, the

signicance of these relationships may contribute to selection and

management of football teams. It also helps forecasting the results of

football competition based on the prole of big ve personality traits. In

order to increase high ranks in football practice, selection for athletics

would focus on persons with high conscientiousness and neuroticism.

Future research might also nd the model of these relationships useful

when expanding athletic departments.

References

1. Piedmont RL (1998) The Revised NEO Personality Inventory: Clinical and

Research Applications. Springer, New York.

2. Sternberg RJ (2000) Handbook of intelligence. New York: Cambridge University

Press.

3. Aidman E, Schoeld G (2004) Personality and Individual Differences in Sport.

(2ndedn), Sport psychology: theory, applications and issues Wiley, Milton,

Australia.

4. McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF (1981) Prole of Mood States manual.

Educational and Industrial Testing Service, San Diego, CA.

5. Newby RW, Simpson S (1991) Personality prole of nonscholarship college

football players. Percept Mot Skills 73: 1083-1089.

6. Leunes A, Nation JR (1982) Saturday’s heroes: a psychological portrait of

college Football players. Journal of Sport Behavior 5: 139-149.

7. Levine RA (2001) Culture and personality studies, 1918-1960: myth and history.

J Pers 69: 803-818.

8. Costa PT, McCrae RR (1992) The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-

PI-R). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

9. Jang KL, McCrae RR, Angleitner A, Riemann R, Livesley WJ (1998) Heritability

of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: support for a hierarchical

model of personality. J Pers Soc Psychol 74: 1556-1565.

10. McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr (2003) Personality in Adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory

perspective. (2ndedn), Guilford Press, New York, USA.

11. Benet-Martinez V, John OP (2000) Toward the Development of Quasi-

Indigenous Personality Constructs. American Behavioral Scientist 44: 141-157.

12. Ozer DJ, Benet-Martínez V (2006) Personality and the prediction of

consequential outcomes. Annu Rev Psychol 57: 401-421.

13. John OP, Srivastava S (1999) The Big Five Trait taxonomy: History,

measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In LA Pervin, OP John (Eds.),

Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–139). New

York: Guilford.

14. Busato VV, Prins FJ, Elshout JJ, Hamaker C (2000) Intellectual ability, learning

style, personality, achievement motivation and academic success of psychology

students in higher education. Pers Indiv Differ 29: 1057-1068.

15. Salgado JF (1997) The Five Factor Model of personality and job performance

in the European Community. J Appl Psychol 82: 30-43.

16. Piedmont RL, Hill DC, Blanco S (1999) Predicting athletic performance using

the ve-factor model of personality. Pers Indiv Differ 27: 769-777.

17. Kovacs M (2008) Relationship between personality and collegiate tennis

rankings. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40: 209-210.

Average of 50-state data Mean Std.Deviation

Football rank 24.78 13.54

Extroversion rank 26.10 14.99

Agreeableness rank 25.78 14.93

Conscientiousness rank 25.84 14.92

Neuroticism rank 26.14 14.98

Openness rank 25.68 14.83

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of Football and the Big Five Personality Traits

Enrollment in local colleges.

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

1. Football rank .22 .39** .41** .12 -.05

2. Extroversion rank .43** .44** -.12 -.31*

3. Agreeableness rank .65** -.18 -.30*

4. Conscientiousness rank -.32* -.12

5. Neuroticism rank .10

6. Openness rank

(**) Correlation is signicant at 0.01 levels (1-tailed)

(*) Correlation is signicant at 0.05 levels (1-tailed)

Table 3: Pearson Correlations of Football Rank, Extroversion Rank, Agreeableness

Rank, Conscientiousness Rank, Neuroticism Rank, and Openness Rank.

*Predictor C E A O N

r (p) .43(.00) .20(.15) .40(.00) -.01(.91) .10(.44)

β (p) .36(.05) .00(.96) .22(.20) .05(.68) .27(.05)

Predictors: C: Conscientiousness; E: Extraversion; A: Agreeableness; O:

Openness; N: Neuroticism

Dependent Variable: Football rank

Table 4: Spearman’s rho Bivariate and Multivariate Contributions–DV=Football

ranks.

Volume 2 • Issue 6 • 1000117

J Sports Med Doping Stud

ISSN: 2161-0673 JSMDS, an open access journal

Citation: Tran X (2012) Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors across 50 States in the U.S. J Sports Med Doping Stud 2:117.

doi:10.4172/2161-0673.1000117

Page 5 of 5

18. Taylor DM, Doria JR (1981) Self-serving and group-serving biases in attribution.

J Soc Psychol 113: 201-211.

19. Peabody D (1988) National characteristics. Cambridge, United Kingdom:

Cambridge University Press and Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

20. Rentfrow P, Gosling S, Potter J (2008) A theory of the emergence, persistence,

and expression of geographic variation in psychological characteristics.

Perspective on Psychological Science 3: 339-369.

21. Kitayama S, Ishii K, Imada T, Takemura K, Ramaswamy J (2006) Voluntary

settlement and the spirit of independence: evidence from Japan’s “Northern

frontier”. J Pers Soc Psychol 91: 369-384.

22. Vasta D (2012) Power Ranking All 50 States by Their College Football

Teams.

23. Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP (2004) Should we trust web-

based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet

questionnaires. Am Psychol 59: 93-104.

24. Benet-Martínez V, John OP (1998) Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and

ethnic groups: multitrait multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and

English. J Pers Soc Psychol 75: 729-750.

25. Cohen J, West SG, Aiken L, Cohen P (2003) Applied multiple regression/

correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, (3rdedn). Mahwah, NJ.:

Erlbaum Associates.

26. Bogg T, Roberts BW (2004) Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors:

a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull

130: 887-919.

27. Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR (2007) The Power

of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic

status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspective

Psych Sci 2: 313-345.