AN ATHLETE’S HUMBLE BEGINNINGS:

A PLACE-BASED NARRATIVE IN NEED OF REPAIR

by

Barbara Lash

A dissertation submitted to the faculty of

The University of North Carolina at Charlotte

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in

Geography

Charlotte

2021

Approved by:

______________________________

Dr. Colleen Hammelman

______________________________

Dr. Heather Smith

______________________________

Dr. Harry Campbell

___________________________

Dr. Chance Lewis

ii

©2021

Barbara Pinson Lash

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

iii

ABSTRACT

BARBARA LASH. An Athlete’s Humble Beginnings:

A Place-Based Narrative in Need of Repair.

(Under the direction of DR. COLLEEN HAMMELMAN)

Sports play a unique role in American culture and act as sources of entertainment and

community identity. Events that include sports are also a microcosm of society that

simultaneously reflects and guides cultural and racial differences that are illuminated by the

journey of the African American athlete. The media depictions of Black athletes as super-

human, aggressive bodies that are products of poor, blighted, and dangerous neighborhoods have

created a dominant humble beginnings narrative that stigmatizes Black athletes and marginalized

neighborhoods. Such depictions create an imagined Black sense of place and space that travels

with the athletes as they move from city to city for their professional careers. Grounded in

Black Geographies, this research discusses the intersections of race, the media-framing of male

athletes, and neighborhood stigma. It provides a new way in which to evaluate marginalized

communities. This research also disrupts the dominant narrative by de-centralizing the Black

body and offering variations of the lived experiences that were shared by 30 Black NFL players.

Understanding alternate storylines creates new spatial imaginaries of marginalized Black

communities and what is needed to improve their quality of life. The dissertation concludes

with a consideration that scholars and journalists should highlight variations of the humble

beginnings experience and share the stories of Black athletes who do not come from humble

beginnings so it may be possible to deconstruct racial and geographic stigma.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to first and foremost thank God for His grace, mercy, confidence, humility and

guidance throughout this four-and-a-half-year journey. I am also extremely grateful for my

husband Jack and daughter Simone who sacrificed precious time to allow me to see this goal

realized. If it were not for their love and support, as well as the encouragement from my parents

Maria, Ralph, Marestta, and John, I would not have completed this journey.

I am also grateful for my advisor, Colleen Hammelman, for her support, guidance,

encouragement and feedback. Her ability to keep me connected to my work in spite of the

pandemic, was truly remarkable. I also thank my committee members – Heather Smith,

Harrison Campbell, and Chance Lewis – for their feedback that helped greatly improve the

outcome of this research. A special thank you also goes to Janni Sorensen for her support

during my initial years in the Geography department.

Many thanks also to Kevin Bostic whose tech savviness saved my work after the

computer “ate my paper,” literally. And finally, I want to express my appreciation for the

athletes who participated in this research. I am forever grateful that you shared your personal

experiences in an effort to show that your NFL journeys are varied, complex and unique.

v

DEDICATION

To

All the athletes who trusted me

with their stories, journeys and experiences.

And my husband Jack and daughter Simone

who also sacrificed to make this a reality.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES x

LIST OF FIGURES xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1

Research Question 2

Brief Overview of Research Findings 3

Road Map 5

Significance of the Research 7

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW 11

Neighborhood Stigmatization 11

Significance of Space and Place 13

Predominately African American Neighborhoods 14

Stigma and Advanced Marginality 17

Media and Stigmatized Storylines 18

African American Athletes 23

Connecting Athletes to Place 24

History of Sport and Black Athlete Stigmatization 25

Media-Framing of Black Athletes 28

Black Geographies 39

Geographic Analysis 40

Carceral City 41

vii

Anti-Racist Scholarship and Critical Race Theory 41

Media-Framing 43

Black Geographies Epistemology 44

The Need for Context When Sharing an Athlete’s Humble Beginnings 47

Research Gaps and Contributions 49

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH DESIGN & METHODS 52

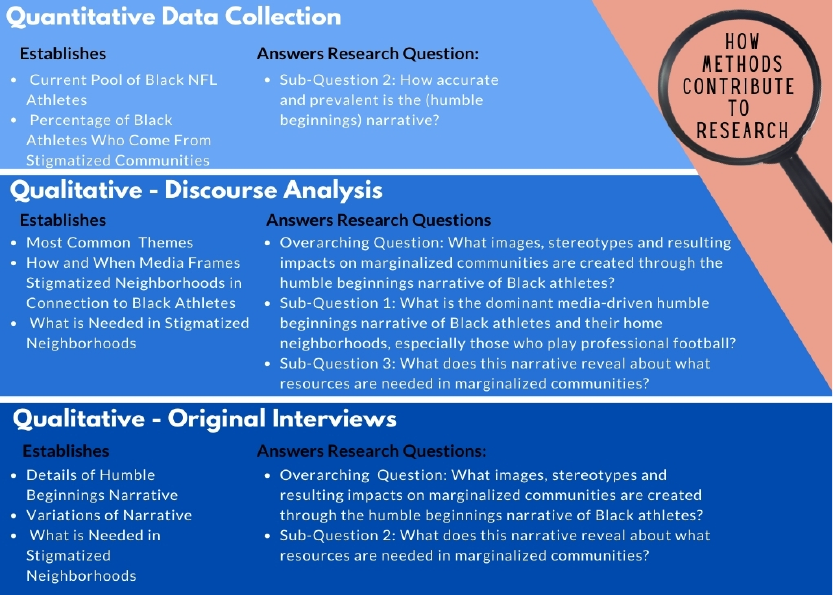

Mixed Methods 52

Reflections as a Researcher, Coach, and Former Journalist 54

Research Design 55

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis 56

Growing up in Multiple Communities 58

High Schools as a Measure of Humble Beginnings 59

Sample Size 60

Analysis and Limitations 61

Qualitative Paradigm—Discourse Analysis 62

Specific Parameters 62

Analysis and Limitations 66

Qualitative Paradigm—Original Interviews 68

Limitations 70

Interview Guides 72

Analysis 74

Methods Summary 76

CHAPTER 4: DOMINANT NARRATIVE, PERSPECTIVE, AND PREVALENCE 78

viii

Stories of Black NFL Players 79

Athletic and Aggressive Super Freak 80

From the Hood 83

Challenging Family Dynamics 87

Using Football as a Way Out 89

Narrative Exceptions 90

Journalist Context 93

Including an Athlete’s Humble Beginnings 94

Black NFL Players on the 2020 Active Roster 100

Black NFL Players from Humble Beginnings 101

Quantitative Data Analysis & Limitations 104

Qualitative Data Analysis & Limitations 105

Chapter Takeaways 105

CHAPTER 5: THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF BLACK NFL PLAYERS 106

Interviewee Profiles and Emergent Themes 107

Theme 1. The Humble Beginnings Narrative Expanded 108

Lived Experiences and the Dominant Narrative Align 111

When Lived Experience and the Dominant Narrative Differ 113

Theme 2. Internalizing Stereotypes 116

Theme 3. The Dominant Media-Driven Beginnings Narrative

Solidifies the Stigma 122

Theme 4. Creating a Mobile Black Sense of Place and Space 125

What is Needed in Marginalized Communities 129

Chapter Takeaways 132

ix

CHAPTER 6: BLACK GEOGRAPHIES & RECOMMENDATIONS 135

Summary of the Dissertation 137

Emerging Themes 139

Significance of the Research 142

Recommendations 144

Recommendations for the Media 144

Recommendations for Black Athletes 146

Recommendations for Sport Leagues 147

Recommendations for Academia 148

Future Research 149

REFERENCES 152

APPENDIX A: INTERVIEW GUIDE (ATHLETE) 168

APPENDIX B: INTERVIEW GUIDE (JOURNALIST) 170

APPENDIX C: NFL ATHLETE PSEUDONYMS AND PROFILES 171

APPENDIX D: PHONE/EMAIL RECRUITMENT SCRIPT FOR ATHLETES 172

APPENDIX E: DIRECT MESSAGE RECRUITMENT SCRIPT FOR ATHLETES 173

APPENDIX F: PHONE/EMAIL RECRUITMENT SCRIPT FOR JOURNALISTS 174

x

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: NBA Player Profiles 46

Table 2: Coding Guide 66

Table 3: Journalist Pseudonyms and Profiles 94

Table 4: Neighborhood Marginality Occurrences 103

Table 5: How Respondents Described Humble Beginnings 110

Table 6: Community Resources Athletes Would Like to See Added 130

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

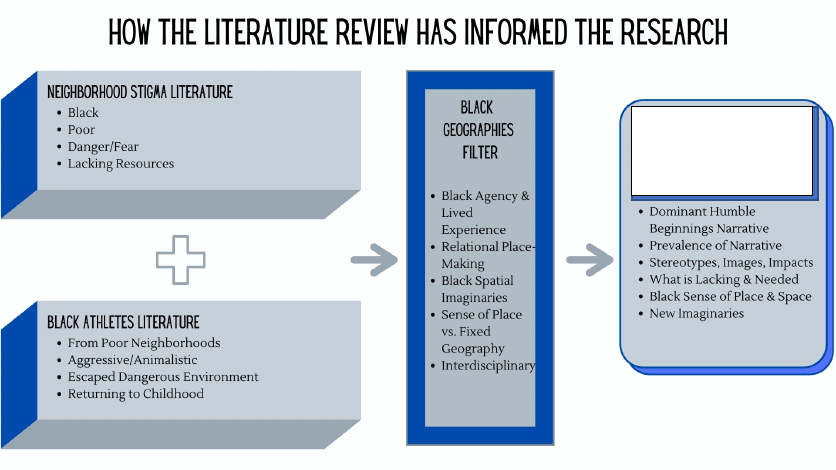

Figure 1: How the Literature Review has Informed the Research 48

Figure 2: How the Methods Contributed to the Collection of Research Data 75

Figure 3: Desire Housing Project 83

Figure 4: Barry Sanders’ Childhood Home 84

Figure 5: Role of Fathers in the Lives of Black NFL Players 87

Figure 6: Marshall Faulk Calculating Plays 92

Figure 7: 2020 Black NFL Players Meeting Neighborhood Marginality Criteria 104

xii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS & TERMS

Hood A marginalized neighborhood with high concentrations of

poverty, crime and violence

League National Football League

MLB Major League Baseball

NBA National Basketball Association

NFL National Football League

Black Sense of Place and Space Spatial identity, or what an individual imagines it is like to

be a or be around a Black athlete from a marginalized

and/or stigmatized community

Community A socially constructed network of people living in the same

place and sharing similar characteristics and/or interests

Neighborhood A spatial construct, location or area surrounding a

particular place

Place Areas/locations/spaces imbued with meaning

Space Physical structures and locations with specific boundaries

Spatial imaginaries Concerned with the spatiality of Black life, and represents

the meanings people give to Black people emerging from

marginalized communities, based on what they see and

what they think they know.

1

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

In March, 2019, chaos erupted within the Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools system when a

high school playoff basketball game was moved from the hosting school to a different school.

The decision came from the North Carolina High School Athletic Association, citing the

gymnasium seating capacity inside West Charlotte High School was insufficient for the highly

publicized quarterfinal matchup (Wertz, 2019a) although it had won the right to host the game

because of its winning record. This decision expanded the discussion from one of mere logistics

to a debate over the disparities between a school that was housed in a marginalized community

and its wealthy suburban counterpart, Ardrey Kell High School (Wertz, 2019b). Such

neighborhood polarization was highlighted by many of the West Charlotte Lions basketball

players, students, and alumni who turned to social media to publicize their belief that the Ardrey

Kell Knights and their fans did not feel comfortable coming to their neighborhood (Wertz,

2019b). That narrative advanced to racial tension after a White player from Ardrey Kell posted

a racial slur when referring to the West Charlotte players, most of whom were Black. Yet

another social media post the night before the game framed one of the Lions star players as a

criminal who was threatening to bring a gun to the game and use it. Police were ready to

intervene until it was proven the post was fake (Wertz, 2019b). But why? Why was the

perception of a violent Black athlete from a poor Black community such an easily accessible

narrative? Why was it almost immediately accepted as a situation that warranted the Black

athlete being contained and controlled? Finally, why was there such an imbalance of resources

to begin with?

2

The game was ultimately played without any violent outbreaks at Vance High School, a

neutral location with a larger seating capacity gymnasium. The White athlete who made the slur

was suspended from participating in athletics, and the district cited his racist behavior as

“repugnant” (Associated Press, 2019, para. 5). The West Charlotte Lions won the game, but

they gained no ground in leveling the playing field in the areas of school resources, and the

athletes did not erase any of the racially-charged perceptions about their neighborhood and

athletes. What the series of events and sentiments leading up to the West Charlotte-Ardrey Kell

playoff game did highlight were the connections between inequitable access to resources

between segmented neighborhoods of privilege and poverty, the perception of fear of stigmatized

Black communities, and a socially produced and shared humble beginnings narrative of Black

athletes (Allen, Lawhon, & Pierce, 2019; Brown, Anderson, & Thompson, 2013; Deeb & Love,

2018; Florida & Adler, 2018; Shields, 1999; Wacquant, 1994, 2010; Wilson, 1997). It also

revealed an outsiders’ imagined sense of Black place and space—a poor environment with

dangerous Black athletes who need to be controlled. It is these connections that this research

explored, which is the place-based narrative that Black athletes often emerge from poor Black

communities plagued with violence and void of the very basic of resources, and further that the

athletes use athletics as an avenue to escape stigmatized geographies.

Research Question

Specifically, this research sought answers to the following overarching question: “What

images, stereotypes, and resulting impacts on marginalized communities are created through the

humble beginnings narrative of Black athletes?” The path to answer this question included an

exploration of the following supporting questions:

3

1. What is the dominant media-driven humble beginnings narrative of Black athletes

and their home neighborhoods, especially the narrative of those who play professional

football?

2. How prevalent and accurate is this narrative compared to the lived experiences of

those athletes?

3. What do this narrative and the lived experiences reveal about the resources that are

needed in marginalized communities?

Brief Overview of Research Findings

The data from this research showed that there is a dominant media-driven humble

beginnings narrative of Black NFL athletes. They are portrayed (a) with tremendous emphasis

on their bodies and physicality, (b) coming from marginalized neighborhoods with few financial

resources, especially if they were raised by a single mother, (c) enduring challenging family

dynamics, and (d) relying on athletics as their ticket out of the ghetto. Because this narrative is

reinforced by local and national sports media, it cements images and ideas that Black athletes are

either dangerous, or that they can be. Another stereotype is that if a Black man lives in a

wealthy neighborhood, his money must have come from either athletics or drug deals. While

the quantitative content analysis from this study showed that a majority of the Black athletes in

the NFL do come from humble beginnings, it was observed through the qualitative analysis of

original interviews that their experiences varied, and they had a strong desire to debunk the

stereotypes. Additionally, the dominant narrative does not portray what is needed in humble

communities. The storylines are relegated to the circumstances the athletes left behind and to

short stories of giving back with football camps that athletes sponsor years after leaving their

childhood neighborhoods. Meanwhile, the players who were interviewed for this dissertation

were very vocal about the needs of their hometowns; they highlighted a variety of resources that

were needed that ranged from neighborhood libraries to Black-owned businesses and daily

schedules that would hold youth accountable for their free time. To ground the research in

4

geography and account for the role of race, I used Black Geographies (McKittrick & Woods,

2007) as the epistemological framework to further explore the research questions and the

ontological positioning to connect Black athletes to stigmatized neighborhoods.

The social identities journalists assign to Black athletes and their bodies, as well as the

National Football League’s (NFL) pattern of commodifying their presumed ability to re-direct

the perceived grit, strength and power it took to escape the ghetto, make the media and the

League complicit in contributing to and normalizing a Black sense of place and space that

simultaneously highlights difference, exception, inclusion and exclusion. This Black sense of

place and space (or what an individual imagines it is like to be a Black athlete from a

marginalized and/or stigmatized neighborhood and community) creates a spatial identity (Eaves,

2017; Hawthorne, 2019; McKittrick, 2011). As a result, most of the athletes interviewed for this

dissertation discussed their emotional challenges and frustrations as they tried to co-author and

negotiate their childhood environments, and as they tried to make sense of new geographies their

NFL career afforded them—geographies from which they had previously been excluded. While

Black Geographies does not explicitly state the level of influence contributors have in the

making of Black communities, Pierce, Martin, and Murphy (2011) argued, “Individuals (and

institutions) may have strong relational ties to multiple communities that allow them to strongly

experience and potentially shape competing place-frames simultaneously” (p. 60). Their

statement suggests that a privileged political power (e.g., the media, the League, government)

can have more influence than the community members themselves. In this dissertation, it was

my intention to extend the relational place-making analysis of Black Geographies in order to

evaluate the significant influence outsiders possess in the making of marginality within Black

neighborhoods, through the lens of Black athletes.

5

Road Map

As a road map to this research, I examined the intersection of geography, race, and

African American male athletes through an analysis of media-driven representations of

stigmatized neighborhoods and Black NFL players. I used the versatility of Black Geographies,

an interdisciplinary approach, as well as determined examples of its relational place-making, the

politics and power dynamics in the making of place and space, and Black agency to illustrate this

intersection. While scholarship in each of these areas (geography, race, and Black athlete

identities) exist in solidarity, I struggled to find a body of literature that connects them and

grounds the journey of the African American athlete in geography and the making of

marginalized and stigmatized Black neighborhoods. The information from this research project

fills a gap in the literature by creating a new approach to studying neighborhood marginalization

and stigma in Black geographies through the lens of Black athletes. Knowledge gained from the

study contribute to the literature by incorporating theory from media framing and the concepts of

space and place.

Neighborhood stigma literature was consulted to establish what classifies areas, as

marginalized (especially in Black and Brown communities), and how those characteristics result

in stigma that reflect on the citizenry (Besbris, Faber, Rich, & Sharkey, 2015; Sampson &

Raudenbush, 2004; Wacquant, 2016). Embedded in this analysis were found evaluations of

space and place in the making of neighborhoods. Media framing literature placed African

American athletes within racialized stereotypes by framing them solely in relation to their bodies

versus White athletes who were depicted in more “passive images” (Johnson & Romney, 2018,

p. 12). The literature also provided two pivotal connections to geography. First, media

framing connected Black athletes to stigmatized neighborhoods by depicting their rise to fame

6

and fall from grace in relation to their humble beginnings (Cole, 1996; Hartmann, 2000; Hylton,

2018; Nike, 2019). The other connection came from framing their superstar status as the reason

they were an exception to the “breakdown, disorder, and impoverishment of the inner city”

(Cole, 1996, p. 368). Along with its interdisciplinary approach to understanding Black agency

in the making of place and space, Black Geographies revealed opportunities and approaches to

disrupt the dominant humble beginnings narrative and re-envision images of what it means to

come from a marginalized and stigmatized community. Scholarship on Black Geographies also

provided an ontological framework to evaluate the actors in relational place-making and

encourage new approaches to evaluating the needs of stigmatized neighborhoods (Allen et al.,

2019; McKittrick, 2011).

Chapter 2 provides the review on three primary literatures: (a) neighborhood

stigmatization, (b) racial media framing of African American athletes, and (c) Black

Geographies. Chapter 3 outlines the mixed-methods design for this research, including a

quantitative content analysis to establish how many Black NFL players come from humble

beginnings and a discourse analysis of pre-existing media stories to establish the dominant

media-driven narrative. Original interviews with sports journalists are discussed to understand

how, when, and why the narrative is dominant, and original interviews with athletes are studied

to understand the lived experience. Chapter 4 presents the results of a discourse analysis that

firmly establishes the dominance of the humble beginnings narrative and also situates

marginalized neighborhoods as a lived experience for the majority of Black NFL players who

were active in the 2020 season. The chapter includes an evaluation of why journalists continually

push forward the humble beginnings narrative. Chapter 5 discusses the lived experiences of

current and former NFL players who grew up in humble beginnings. Along with highlighting

7

experiences that directly correlate with the dominant narrative, this chapter also illustrates

significant variations and shares more than a dozen resources athletes feel are needed in

marginalized communities. Chapter 6 concludes the study with a discussion of how this

research expands the application of Black Geographies, portrays the professional Black athlete

journey in a new way through which to study neighborhood stigma and introduces future

research opportunities. Throughout the paper, several terms are used interchangeably. These

include (a) Black and African American, (b) Brown, Hispanic, and Latino, and (c) sport, sports,

and athletics.

Significance of the Research

This research is significant because of the role of sports in American culture. Not only is

it a microcosm of society, but “large numbers of Americans across racial lines interact with sport

and are impacted by its remarkable racial dynamics” (Hartmann, 2000, p. 231). Through their

celebrity status, African American athletes are positioned to both illuminate struggles of

marginalized communities and sensationalize the ability to transcend their circumstances. This

research study is grounded in geography and presents the connection between race, the media-

framing of African American male athletes, and neighborhood marginalization and stigma—a

connection that needs further study in modern academic scholarship. As a result, it contributes

to the literature on neighborhood marginalization and stigmatization, racial media framing of

athletes, and Black Geographies. In traditional studies on marginalized neighborhoods and

stigmatized communities, researchers spend significant time unpacking what constitutes

marginality and stigma and their impact on everyday residents. This research project provides a

new lens through which to evaluate marginalized communities and determine what is needed in

them by understanding the unique positionality of athletes to circumvent social problems.

8

Juxtaposing the dominant media-driven humble beginnings narrative to examples of the athletes’

lived experiences also advances the debate on what is needed to improve the quality of life in

marginalized neighborhoods. In my interviews with athletes, I asked them what resource they

felt their childhood neighborhood could have benefited from. It took 25 interviews before I

heard the same primary resource repeated (see Table 6). This is important in prompting

scholars, planners, governments, and other change-makers to not generalize the needs of

marginalized communities, but rather, to evaluate them and interpret their needs individually.

In racial media framing of athletes, scholars have firmly established socially constructed

stereotypes of Black athletes and the role of sport to “reinforce and reproduce images, ideas and

social practices that are thoroughly racialized, if not simply racist” (Hartmann, 2000, p. 230).

Those racial undertones shape how others perceive racial difference (Deeb & Love, 2018;

Johnson & Romney, 2018). What is missing is a definitive and in-depth evaluation of Black

athletes and their connection to urban geography that is grounded in the geography discipline.

Other than sociology of sport and behavioral science disciplines, scholars rarely explicitly

discuss Black athletes as representatives of inner cities (Andrews & Silk, 2010; Cole, 1996;

Edwards, 2000; Hartmann, 2000; Hylton, 2018). Instead, the conversations are typically

mapped out in popular media (Nike, 2019) and relegated to sport identity and the

commodification of ghetto-centric marketing rather than creating new spatial imaginaries of race

and urban landscapes (Andrews & Silk, 2010; Carrington, 2010). Even sports geography

literature that acknowledges the spatial and location properties of athletics (including global

identities through sports facilities) omits the connection at the micro and inner-city level (Bale,

2002; Connolly & Dolan, 2018). My contribution to media-framing and geographic literature is

the specific consideration that while Black professional football players are more often than not

9

products of concentrated urban geographies and subject to marginalization and stigma, that is not

the only scenario. Instead, their lived experiences are more complex that often presented in the

media. This research expands on the evaluation of athletes’ experiences and conversations

about them to provide a greater understanding of the variety of needs of stigmatized

communities. Geographers should reframe the conversation to leverage the many versions of

the lived experience and the privileges offered by sports to push past a singular way to see Black

athletes and marginalized neighborhoods.

Black Geographies account for multiple articulations of place and encourages the use a

variety of methodologies to better understand Black agency and provide the glue that holds race,

place, and spatial imaginaries together (Allen et al., 2019; Hawthorne, 2019). It has been used

to study feminism, the carceral city, Black queer communities, Latinx geographies, public health

disparities, and ecological injustices (Black Geographies Specialty Group, 2021; Hawthorne,

2019; Ramírez, 2015). My research contributes to Black Geographies literature by expanding

its application to the study of marginalized and stigmatized communities, especially as

experienced by the journey of a Black male athlete and those who manipulate neighborhood

politics and power structures to support his escape from the neighborhood. Furthermore, Black

geographical scholarship does not see place as a fixed geographical location, but as an ever-

evolving sense of place constructed by social, political, socio-economic and other fixed and fluid

factors, including how Blacks relate to those environments (Allen et al., 2019). My findings

build on the flexibility of this relational place-making to firmly establish a mobile Black sense of

place and space that adheres to Black professional athletes whether or not they come from

marginalized communities. According to the data from the interviews conducted for this

dissertation, Black athletes experience tremendous stress trying to counter racialized stereotypes

10

that relegate them to nothing more than strong, mindless Black bodies, especially if their

physical locations have changed from humble beginnings to more affluent neighborhoods. By

elaborating on Black Geographies’ acknowledgement of an imagined sense of what it means to

be from Black neighborhoods, expanding its application as a framework to understand

neighborhood stigma and marginalization, and pulling in the contributions to Black athlete media

framing, this research also provides recommendations for the media, academia, athletes, and the

NFL to re-envision multiple articulations of place and space within and outside of marginalized

communities.

11

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

The research for this dissertation was based on literature in three primary areas of study:

neighborhood stigmatization, media-framing of African American athletes and Black

Geographies. Chapter 2 provides a literature review of each area, while also incorporating

supporting concepts from spatial stigmatization and Black athlete identity. The review of

literature includes a discussion of neighborhood stigmatization, with particular attention to the

making and impact of place and space, the meaning people give to their respective spaces and

places, the production of advanced marginality, and the role of storytelling and media in creating

and reinforcing the stigma. One of the goals of this dissertation was to give a thorough and

vivid picture of stigmatized neighborhoods and their Black and Brown citizenry in order to better

understand how African American athletes are depicted in the media as products of humble

beginnings.

Neighborhood Stigmatization

Regions, counties, cities, towns and neighborhoods are often divided and categorized by

a combination of socially constructed factors including socioeconomic status, race, property

values, school performance and crime. Whether an area is rural or urban, has a population in

the thousands, hundred-thousands or millions, whether it is close to jobs and cultural amenities

—all of these characteristics help define neighborhoods and how they are divided (Anderson et

al., 2003; Florida, 2017; Ley, 1996). Studying these physical, cultural, social, political and

economic geographical aspects can help scholars understand physical and environmental

conditions, the people who inhabit various places, and capitalistic agendas that shape their space

(Delmelle, 2017; Hernandez, 2009; Hertz, 2015). These studies can also be used to frame

neighborhoods in one of three broad categories: rich, middle/working class and poor. More

12

specifically, neighborhoods are often understood to be one of three types: (a) rich, affluent or

advantaged areas that house the professional creative class, (b) middle and working-class

communities for white- and blue-collar level workers, and (c) disadvantaged or marginalized

neighborhoods that house the poor and service class (Florida & Adler, 2018). The latter is often

accompanied by stigma that defines how outsiders view and regard a neighborhood and its

residents (with the help of avenues like politics and the media), and artificially position residents

living within marginalized neighborhoods so that the stigma are incorporated, or individuals feel

the need to defend their neighborhood and community’s reputation (August, 2014; Keene &

Padilla, 2010). The affluent communities are traditionally populated by Whites while poor,

marginalized, and stigmatized neighborhoods are historically comprised of mostly Black and

Brown citizenry (Florida, 2017; Florida & Adler, 2018; Wacquant, 1994, 2010, 2016).

Importantly, the impressions and expectations of neighborhoods (and community) are socially

constructed through relationships, discourse (such as media framing), and material

circumstances. During my review of the literature, I observed that many of the scholarly works

used for this paper were rooted in traditional geographical thought, including economic

geography, and did not specifically correlate stigma and poverty to Black and Latino

communities. However, Darden’s (1987) work introduced significant connections between race

and geography, explaining the power of education, occupation and income in determining the

access racial groups have to neighborhoods. Additionally, all literature were evaluated with a

particular emphasis on African American citizenry, as well as geographical thought and

economic geography since all of these factors influenced participants of this study, Black

athletes.

13

Significance of space and place. Understanding neighborhood stigma requires

comprehending the physical characteristics and outcomes of marginalized geographies as well as

the meaning attached to them. A neighborhood’s reputation, for example, denotes the meaning

insiders and/or outsiders have attached to the area (Keene & Padilla, 2010). In this case, a

neighborhood’s bad reputation or stigma operates on a place-space continuum with visible and

non-visible boundaries and characteristics. Understanding this factor is crucial to evaluating the

foundation of my research question that dealt with what it means to come from a humble

beginning and the criteria ultimately used to measure it.

Neighborhoods are the products of physical as well as non-physical components.

Physically, they are defined as homes, buildings, and land locations with fixed boundaries, that

provide “a deeply held human need to organize space by creating arbitrary borders, boundaries,

and districts” (Cutter, Golledge, & Graf, 2002, p. 308). The need for physical locations,

boundaries, borders, and districts highlights the existence of different realities for people living

in ghettos versus those in single family suburban homes separated by white picket fences. But

the very idea that an area would be referred to as a ghetto introduces the abstract nature of place

(Relph, 2013; Tuan, 1974, 1977). According to Tuan (1977), spaces start as areas that can be

occupied, and over time, they transform to locations with memories, values, and impressions to

help explain how individuals act in their environments (Tuan, 1974). While those values and

what they symbolize can vary from person to person, group to group, and community to

community, the cultural constructs that denote one area as a suburb and another as a ghetto also

represent bounded spatial representations (Keene & Padilla, 2010; Wacquant, 1994). And when

those physical spaces are characterized by high poverty rates, violent crime, food deserts, low

property values, and are comprised of mostly renters, low performing schools, and neighborhood

14

schools with a Title I status, residents become vilified for their connection to their space and to

their location (Wacquant, 1994). These and other neighborhood characteristics discussed in this

chapter guided my choice of poverty rates, violent crime exposure, school performance, and Title

I school status as the characteristics to broadly determine if the 2020 pool of Black NFL players

came from humble beginnings.

Predominately African American neighborhoods. Impoverished, blighted, crime-

ridden, low performing schools, food desert, dangerous—all of these terms and phrases are used

to describe stigmatized communities (Ettema & Peer, 1996). Juxtaposed to these

categorizations are racial identity terms such as African Americans/Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos

(Anderson et al., 2003; Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004; Wacquant, 2010). When used in

tandem, these descriptors portray a neighborhood as either lacking in resources, in need of repair,

or a lost cause (Florida & Adler, 2018; Wacquant, 1994, 2010, 2016) and are potential targets for

some of society’s unwelcome elements including low-rent motels, rehabilitation clinics, and

prisons (Sandercock & Taylor, 1999). Even more powerful is when these characteristics are

connected to fear, because this creates momentum to solidify a neighborhood’s negative

reputation. Whether it is fear that a person will be harmed when visiting a stigmatized

neighborhood, fear that crime will spill over to White communities, or fear that the same

disinvestment that contributes to advanced marginality will occur in once affluent or post-

gentrified communities—fear and stigmatization go hand in hand (Florida & Adler, 2018; Kern,

2010; Smith, 1996). The connection to fear emerges in marginalization literature which

positions stigmatization as spatial relegation to the leftover, ex-urban concentrated places

plagued by poverty, divestment, crime, violence, and the perception of violence that draws on

social, cultural and even political dimensions (Hernandez, 2009; Wacquant, 1994). When fear

15

of crime spills over and outside of the danger-zones, it alters the reactions of outsiders and

negatively impacts surrounding communities (Bonds, 2019; Goetz, 2011; Wacquant, 2010).

This was demonstrated in the events described at the beginning of Chapter 1; the police came

close to having to intervene after there were reports of the stereotypical depiction of a gun-toting

Black star athlete from a poor community. The fear of Black neighborhoods and the people

emerging from these impoverished communities is so ingrained, and the news of incidents are so

often repeated that the stigma stay tethered to star athletes who emerge from such communities

and are points of note whether they experience significant triumphs or failures (Berry & Smith,

2000; The Famous People, n.d; Lapchick, 2019). That fear and other imaginary beliefs often

prompt outsiders to impose their negative stereotypes on athletes. In one particular case, Fox

News reporter Laura Ingram criticized NBA star LeBron James for his “barely intelligible, not to

mention ungrammatical take on President Trump” after Mr. Trump won the presidency (Raf

Productions, 2018). During her television program, Ingram called James’s comments ignorant

and warned others not to leave high school early like James did. She ended her rant by telling

James and the NBA’s Kevin Durant to “shut up and dribble” (Raf Productions, 2018).

Additionally, the fear of the unknown drives the “golden ghettos” phenomena used to describe

Black athletes at predominately White colleges who find themselves isolated (Bourdieu, 1988, p.

153), “where conservatives were reluctant to talk with them because they were black, while

liberals were hesitant to converse with them because they were athletes” (Hartmann, 2000, p.

229).

Baumer (1985) noted that the residents living within so-called crime-ridden areas can

differentiate between the perception of crime and actual crime, but there is no awareness of the

difference for outsiders. The ability to differentiate the real from the imaginary is especially

16

difficult when information outsiders receive is delivered by trusted sources like local news

stations (Campbell, LeDuff, Jenkins, & Brown, 2011; Ettema & Peer, 1996). As a result, news

outlets become key contributors to the making of Black Geographies. And when the majority of

the crime stories show alleged Black perpetrators, they advance the perceived need for policing

and a push for a carceral city with racialized surveillance practices existing beyond prison walls

(Bonds, 2019; Gilmore, 1999; Thomas & Magilvy, 2011). The longer communities of color are

believed to have negative reputations, the more those storylines become adopted by outsiders

and, to some extent, insiders, and the harder it becomes to shed the stigma (August, 2014; Goetz,

2011; Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004). Conversely, stories that shape affluent areas as clean,

prosperous, and desirable help increase property values, steer continued resources for desired

characteristics and amenities like nearby shopping, breweries, and high performing schools with

thriving extra-curricular activities and well-equipped athletic programs—all elements that

positively affect perceptions of self (August, 2014).

Skogan (1986) introduced another perspective of insiders or people who live within

neighborhoods and are routinely portrayed as dangerous—that fear can prompt them to withdraw

from those neighborhoods. Such actions weaken the social structure and negatively affect

quality of life factors. Furthermore, some people who are exposed long-term to impoverished

communities and clusters of disorder adopt feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness,

manifesting the perceived disorder into real signs of distress and physical decline (Sampson &

Raudenbush, 2004). As it pertains to Black athletes, Powell (2008) noted a particular trend of

some to disassociate themselves from stigmatized communities and backgrounds because they

do not want the social responsibility of fixing all their community’s problems, nor do they want

to be spokespersons for the Black race. Some researchers claim Black athletes fear losing social

17

status and even endorsement dollars if they are associated with a stigmatized community or are

considered a voice for racial justice (Brown et al., 2013; Martin, 2018; Reid, 2017). This was

happening even though the Black Lives Matter movement underway at the writing of this paper

has shown some athletes feel empowered to use their platform to stand for social justice

(Blackwell, 2020; D. Davies, 2020).

Stigma and advanced marginality. The narrative of a poor, Black, blighted, and

dangerous neighborhood is used to justify both the label and actions of advanced marginality—

disinvestment and voids of investment and renovation dollars coming in (Brenner & Schmid,

2015). Disinvestment and neighborhood abandonment literature are often rooted in discussions

of urban decline and the broken windows theory (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004). Brenner and

Schmid (2015) framed these perceptions as significant causes of territorial inequality, the

recognition of contradictions of rapid urbanization growth in some neighborhoods, and the

stagnation and shrinkage of other communities. These occurrences often happen simultaneously

or in close proximity to one another. Social and economic exclusion can take on many forms

including building abandonment, investors who fail to maintain their properties, a school district

that does not repair damaged athletic fields for all its schools, or a county that fails to manage the

upkeep or creation of parks and areas of recreation to match an area’s young active demographic.

All of these factors play a role in deepening financial and social disparities (Edwards, 2000;

Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004; Sandercock & Taylor, 1999).

Such widening of financial and social disparities brought on by divestment or investment

that often depreciates land can also intensify stigmatization of these urban clusters (Roy, 2011;

Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004; Wacquant, 2016), creating what Wacquant (2016) refers to as

hyper-ghettos. Examples are projects like Section 8 housing, toxic waste sites, power grids,

18

airports, and prisons; these developments easily spiral already troubled areas into advanced

marginality and divestment (Rennie-Short, 2013; C. Thomas, 2018). Soja (2010) likened such

examples of spatial injustice to an omnipresence of geographically uneven development. Again,

although it is not explicitly stated, these neighborhoods are home to predominately Black and

Brown residents. Therefore, when policies reduce government intervention and programs such

as welfare that once safeguarded society’s most vulnerable, even more African Americans are

plunged into advanced marginality (Manalansan, 2005). Meanwhile, the residents from areas of

advanced marginality and prolonged stigma experience more than exclusion and social, civil, and

financial disparities. Internalizing the negative storylines are detrimental effects of

neighborhood stigmatization (Ettema & Peer, 1996; Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004). This

further explains why some athletes from severely marginalized places distance themselves from

their home zip codes and the stigma attached to them (Powell, 2008). However, during this

research project, there was also an exploration concerned with the extent to which advanced

marginality prompts successful African American athletes to embrace their humble beginnings

and return to their home communities and give back to where they lived as children. That

exploration culminated into this research firmly establishing a Black spatiality or sense of place

and space that also dictates how athletes interact with new environments throughout their career.

Media and stigmatized storylines. Government, academia, and the news media all

play integral roles in dispersing stigmatized neighborhood and community narratives (Goetz,

2011). From national to local government, agendas often drive alienating actions by controlling

capital from one region to another and are based on social, political and cultural criteria

(Hernandez, 2009). Academia contributes to neighborhood stigmatization by using data to

magnify the link between low socioeconomic areas including public housing and spaces and

19

places with a majority Black and Brown population (Allen et al., 2019; Derickson, 2017).

Academic journals then assign these places and spaces labels such as dysfunctional,

uninhabitable and crime-ridden (Goetz, 2011). Literature in Black Geographies states this

traditional approach to geographical studies reinforces displacement narratives (Allen et al.,

2019; Hawthorne, 2019; McKittrick, 2016). As for the media’s role in sharing stigmatized

storylines, it has a significantly large and universal effect on neighborhood stigma (Campbell et

al., 2011; Stack & Kelly, 2006).

Whether the information comes from mainstream news, sports reporting or popular

culture stories, the media produces knowledge, shapes opinion, and reflects society while

typically being accepted as fact and truth (Brown et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2011; Stack &

Kelly, 2006). And these stories are often negative. Studies have shown that the facts and truths

that newspapers and television news stations share routinely highlight the denigration and

deterioration of place (August, 2014). Traditional news coverage, and in some cases sports

coverage, are causal dynamics of fear, and mainstream media traditionally frames stories with a

racialized and stigmatized viewpoint through which news consumers develop and relate to social

constructs (Berry & Smith, 2000; Campbell et al., 2011; Deeb & Love, 2018; Muschert, 2009;

Yanich, 1998). Television news, in particular, has been a trusted source since its inception in

the 1940s, meeting the test of public service and wielding the power to shape perceptions and

frame social issues (Leong, 2017; Ponce de Leon, 2016). It also plays a significant role in

geographically shaping communities by unfolding the agendas of public and private developers

to manipulate land use (August, 2014; Ley, 1996; Wacquant, 2016). Amid the decline of the

newspaper industry and despite the introduction of social media and internet-based news sources,

the global influence of television to create and change perceptions about any given topic, event,

20

neighborhood, or community remains strong today (Albarran, 2010; Muschert, 2009). As a

result, when the storylines on news channels portray neighborhoods in a negative light, they

negatively affect quality of life factors and can even change the landscape of once thriving

neighborhoods (Skogan, 1986). When those storylines and accompanying images are repeated

over a period of time, as happens in stories that are centered on poor African American

communities, outsiders are more likely to adopt the community’s news-driven negative

reputation, and stigmatize the areas and residents as bad (Campbell et al., 2011; S. Cunningham,

2001). When the crime segments routinely highlight arrests and court appearances, and prison

convictions disproportionately show Blacks as perpetrators, these portrayals cements the

viewers’ notion that African Americans are more involved in crime than their White counterparts

(Berry & Smith, 2000; Campbell et al., 2011; Gilmore, 1999).

News coverage propelled and dominated by an emphasis on crime is not a cohesive look

at any community; yet it is a common practice for a station to focus most of its reporting on

crime, tragedy, and lack (Campbell et al., 2011). However, this creates an inflated undesirable

image of any neighborhood with repeat criminal occurrences that devalues space and place.

Such a skewed stance ultimately shapes urban geography by steering outsiders away from living,

working, and investing in bad and fearful neighborhoods even though they can afford to live

there (Hernandez, 2009).

There are stations, programs, and journalists in the mass media who practice holistic

reporting, who call out racial disparities, and who report from a place of care, accuracy, and

humanity. The tragedy of September 11, 2001, and the 2020 Covid19 pandemic have

demonstrated the media’s ability to unite communities and perspectives. Yet for the most part,

network conglomerates have been historically driven by capitalism and thrive on mottos such as

21

“if it bleeds it leads” that push sensationalistic storylines (Campbell et al., 2011; Lapchick,

2019). The Hidden Valley community in Charlotte, North Carolina is a prime example.

I began working with the Hidden Valley community in 2018 as a University of North

Carolina at Charlotte Ph.D. student and researcher with the Charlotte Action Research Project.

My work involved creating a documentary based on original interviews with residents and

employees. The purpose of the interviews was to counter the stigma the neighborhood received

after a decade of gang activity (Pitkin, 2013). My work uncovered that Hidden Valley started as

a fairytale-themed White community in 1959 and transitioned to an affluent Black neighborhood

in the 1970s (Carter, 2012). It then transitioned to a low-income, nationally-known gang-

infiltrated Black community in the 1990s, and changed once again to become a relatively quiet

mixed community of homeowners and renters with a significant senior population of

predominately African Americans and a growing Latino population by 2020 (Carter, 2012;

Gangland, 2009; Wickersham, 2018). Personal interviews included in the documentary

“Charlotte’s Hidden Valley Neighborhood—The Lived Experience” (Lash, 2021) were based on

the citizens’ lived experiences, and the documentary corroborated the community’s history. The

decade-long reign of the Hidden Valley Kings gang attracted steady reporting on Charlotte

television news stations, newspapers, and pop culture magazines, as well as national exposure on

the History Channel in a television series called “Gangland Documentaries” (Gangland, 2009;

Wootson, 2018). The episode was subsequently re-published online and has received hundreds

of thousands of views via various links on YouTube and through subscriptions to the Gangland

series (Gangland, 2009). As a result, the neighborhood was still fighting that stigma in 2019,

even though the gang was eradicated 12 years before in 2007 (Wickersham, 2018; Wootson,

2018). According to personal interviews with residents conducted in 2019 for the documentary

22

on the lived experience (Lash, 2021), the media continued to depict a crime-ridden area, and

Charlotte reporters claimed crimes were still happening in Hidden Valley, when in fact they were

happening on the outskirts. Here are examples from residents Marjorie Parker and John Wall,

respectively:

It’s always never in Hidden Valley. Meaning that, they will label everything Hidden

Valley, and it could be Sugar Creek Road, it could be the apartments off of North Drive. I

will immediately look for, where is this location? Because, I know that it’s not Hidden

Valley. Just recently, we did have an incident that happened on Spring Garden. It was

actually in Hidden Valley. I was like, wow, that is Hidden Valley. I couldn’t believe it.

You know? (Lash, 2021)

I can tell you that our lobbying, our advocacy has paid off. Because there have been some

incidents recently in the area that was not attributed to being in Hidden Valley. And that

is some progress that we’ve made in media relations. (Lash, 2021)

This is just the beginning of the discontent and struggle with some of the media coverage

on this stigmatized community that continues to put residents in a position to counter the stigma,

as noted by resident Saundra Jackson:

They had a negative attitude about it, and I told them until you come into the

neighborhood or visit someone in the neighborhood, then you shouldn’t go by what you

hear. I said, “We don’t have any more crime in our neighborhood than they have in yours

or in Southside, where they think there is no crime, you know?” Everything is quiet to

me, but at the same time, I’m not out running around looking for anything, either

[laughs]. (Lash, 2021)

Natasha Witherspoon grew up in Hidden Valley, and her parents still resided there at the

writing of this dissertation. She described having to defend her community to her middle-aged

counterparts who watched the prolonged stigmatized coverage of Hidden Valley during and

since the repeated news stories on the Hidden Valley Kings gang:

That’s what the media doesn’t show is the majority of, I would say my peer group and

my brother’s peer group as well, most of us are college-educated professionals,

successful careers, law-abiding citizens, you know, raising good families. But you don’t

hear about that. (Lash, 2021)

23

Another Hidden Valley resident, Marjorie Parker, also reflected, “[The media] creates a negative

perception in folks and it’s hard to change those perceptions, unless they come and live in

Hidden Valley. People will feel sorry for me” (Lash, 2021).

According to Ettema and Peer (1996), Parker’s assertion could be a by-product of a

neighborhood receiving ongoing negative attention—that the journalists themselves find it

difficult to share positive stories or detach negative narratives about communities they have

repeatedly been framing as dangerous, deficient, or economically depressed. Nonetheless,

traditional news media is considered to be a primary and trusted vehicle people use to learn about

themselves and communities around them; as a result, this media platform wields tremendous

influence in shaping the perceptions of its readers and viewers (Stack & Kelly, 2006). Fear and

the media’s framing of marginalized communities play a crucial role in stigmatizing a

neighborhood (Stack & Kelly, 2006), and lived experiences are often very different from the

created imaginaries and the rhetoric of stigmatization (August, 2014; Baumer, 1985). The

media’s power to shape perceptions and reinforce stigma are even more powerful when the

subjects receiving negative coverage are public figures such as professional athletes (Brown et

al., 2013). When the athletes are Black, it appears to be automatic that their stigmatized home

communities are pulled into the storyline, if applicable (Brown et al., 2013; Lapchick, 2019;

Powell, 2008).

African American Athletes

During the literature review, research was found on stigmatized neighborhoods with

predominately African American residents, including how the stigma are shaped and reinforced

through neighborhood classifications, the perception of fear, governmental policies, investments,

divestments, academia, and media framing. This section of the paper is centered on Blacks in

24

sports, how they have been historically stigmatized, and how the media has helped shaped that

perception. Geography is connected to the topic by introducing the conditions that lead the

media to mention an athlete’s childhood neighborhood and to create a narrative shared in popular

media that African American athletes come from stigmatized communities. This type of media

presentation results in a fluid sense of Black space and place (Hawthorne, 2019).

Connecting athletes to place. Similar to race not being specifically stated in much of

the stigmatized neighborhood literature studied for the literature review, the link to impoverished

home zip codes is not always explicit in the shared narrative of Black athletes and is especially

absent in the literature on the beginning of formal sports in the United States (Berry & Smith,

2000; Edwards, 2000). To fill this void, two key concepts were considered for this dissertation:

(a) sport is subject to the same social and political factors at play in the country and (b) framing

of geography can include a sense of place rather than a fixed location (Deeb & Love, 2018;

Hawthorne, 2019; McKittrick, 2006; Ross, 2000). First, it is important to assert that

professional athletics is a microcosm of American culture that has historically mirrored the

country’s segregated makeup (Brown et al., 2013; Christesen, 2007; Goff et al., 2002; Powell,

2008). This assertion is based on the reality that Blacks lived in poorer neighborhoods than did

Whites from the abolishment of slavery, through the Jim Crow era, and through the Civil Rights

era.

When the post-civil rights period is examined, examples of geographically-based

disparities are to be found. P. Cunningham (2009) stated that Black NFL and NBA players

come from Black stigmatized communities. Nonetheless, community-based storylines are more

likely to surface only when a Black athlete accomplishes something extraordinary such as

winning a championship, or when the athletes draw attention to embattled neighborhoods by

25

returning to build things including schools or when they host camps; athletes are also noticed

when they are outspoken, controversial, or accused of a crime (Brown et al., 2013; Powell,

2008). Even when the reference to an athlete’s stigmatized community is not explicitly stated,

Powell (2008) pointed out that language like “street credibility” and being from the “hood” (pp.

197 & 200, respectively) connect Black athletes with Black places and spaces.

The position of place in evaluations of literature on Black professional athletes also relies

on relational place-making, a key Black Geographies concept that is evaluated and discussed

throughout this study. Descriptors for African American athletes are rooted in historical

racialized ideologies and policies that have restricted the role of Blacks in professional athletics

and are tied to the media’s propensity to frame them as different and inferior to White athletes

(Berry & Smith, 2000; Deeb & Love, 2018; Ross, 2000). Socially constructed beliefs such as

the notion that Blacks are more animalistic and less intelligent were the initial storylines in

professional sports that created an imagined idea for White athletes of what it would mean to

play alongside Black teammates (McKittrick, 2014; Ramírez, 2015). Contemporary White-

racial framing is more place-specific because it leans on the narrative that star Black athletes

come from inferior, dangerous, and impoverished backgrounds to which they are always

connected (Deeb & Love, 2018; Edwards, 2000). Therefore, it can be helpful to understand

how these attitudes developed.

History of sport and Black athlete stigmatization. An exploration of the evolution of

the reasons behind the stigmatization of African American athletes offers insight into the various

perceptions of them. One of these perceptions is that they are athletically inclined individuals

with savage-like tendencies. There is also the notion that when they become elite athletes, they

26

are just one decision or mistake away from their brutal stigmatized beginnings. Therefore, it is

helpful to briefly trace the evolution of the Black athletes in the United States.

Ironically, sport was inclusive, and in some cases dominated by Blacks before the Jim

Crow era (Ross, 2000). Horse racing is one of the earliest examples. In 1875, the Kentucky

Derby’s inaugural year, 13 of the 14 jockeys were Black, although they received less than 5% of

the earnings the horse’s owner received (Ross, 2000, p. 3). When the sport began formalizing,

and jockeys were first licensed in 1894, Ross reported that Blacks were denied credentials

altogether. That was also the trend for American baseball, football, and to some extent

basketball, as state and local laws began to make legal public segregation in the late 1890s,

reversing what had been a growing trend of Blacks playing alongside White players (Ross,

2000).

In baseball, for example, some teams employed a few Black players in the 1870s, while

the rest played on all Black teams, some Latin squads, and in the Canadian league (The People

History, 2020; Ross, 2000). The attempt of more Blacks to join the more prominent and

lucrative White minor league teams was denied in 1867, and the attempt to join what is known

today as Major League Baseball (MLB) in 1876 ended with a gentleman’s agreement that kept

Blacks out of the National League (History, 2017). Even though American football was first

established 30 years after baseball, the few Black players who were playing alongside Whites

faced the same segregation laws when NFL owners “informally agreed to ban black players”

(NFL Pro Football Operations, 2020, para. 3). Both examples highlight White exclusionary

decisions that did not hinge necessarily on the neighborhoods the athletes were from; rather, they

were excluded because of the sense of place and space they represented, including their Black

27

style of play and all the imagined visions that Whites had about Black players as violent and out

of control (Brown et al., 2013; Gilmore, 1999; McKittrick, 2014; Ramírez, 2015).

Because sport is considered a reflection of modern American culture, it simultaneously

guides, mirrors, and reinforces how people view and interact with society (Brown et al., 2013;

Christesen 2007; Goff et al., 2002; Giulianotti, 2016; Powell, 2008; Ritzer, 2008). In addition to

the racialized narratives of White, Black, and Latino athletes, there was an increase in micro-

aggressive language that reinforced the stigma athletes of color faced (Brown et al., 2013; Deeb

& Love, 2018; History, 2017, 2020). The Negro League in baseball is a prime example. It was

established in the 1920s and began to gain the attention of White fans after White major league

stars were called to fight in World War II, causing their team membership to decline (Garbett,

2000). White fans seemed to like how the Black players stole bases, pitched, and hit home runs;

they enjoyed what was described as “their showy and aggressive style” (Garbett, 2000, p. 56).

Even when baseball was integrated in 1947 when Negro League player Jackie Robinson broke

the MLB color barrier, his addition was framed with micro-aggressive language. When

addressing his decision to the press, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey referred to the

struggles of Robinson’s segregated past as strengths and a “fighting spirit” that would help him

on the baseball field (Garbett, 2000, p. 59). Although that fighting spirit and the amazing

athletic abilities of Robinson and other Black baseball and football players who later joined him

in the professional ranks were celebrated, the players were still subjected to hostility and

discrimination; they were stigmatized and subject to derogatory language including being called

the N-word from fans in the stands (Garbett, 2000; Ross, 2000). Polarizing language, lower

wages, and exclusionary practices like keeping Black players out of the team hotels are non-

material spatial actions that created a Black sense of place within a White-dominated space

28

(Hawthorne, 2019). This idea of Black agency congruent with the social and political climate of

segregated neighborhoods allowed for an early connection between Black athletes and

stigmatized neighborhoods. With the growth of professional basketball and the growth of the

media’s power to describe athletes, more examples of this biased perception surfaced.

Media-Framing of Black athletes. Similar to the news media coverage of stigmatized

communities, mass media portrayals of athletics and sports-related stories became the avenues

through which Americans learned to further interpret and apply Eurocentric perceptions of race,

place, and space (Brown et al., 2013; Ross, 2000). The more coverage there was of Black

athletes, the wider the media’s influence grew. And like sport itself, sport media’s roots are

grounded in a White standard and a Eurocentric modernity that established White men as

America’s first athletes and the American standard (McChesney,1989; McKittrick, 2011). By

the late 1800s, White sports writers were so influential that they began taking on celebrity status.

In the 1920s, America had entered into what McChesney (1989) dubbed the Golden Age of

Sports Reporting and by the 1930s, 80% of male readers regularly read about sports. The

popularity of newspaper coverage of sports created the demand for storylines outside the ring,

court, and field, and according to McChesney (1989), the love affair between mass-media and

athletics jumped to the television screen in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The annual network

sports programming grew from 787 hours in 1974 to 1,700 hours in in 1984 (McChesney, 1989,

p. 63). At every step of growth, the predominately White reporters and television anchors

exercised celebrity-level influence. They framed White athletes as smart, talented, and heroic,

and Black athletes were described as aggressive and lacking intelligence; such views were

widely accepted as the norm (Brown et al., 2013; Garbett, 2000; McChesney, 1989; Ross, 2000).

29

Researchers on the stigmatization of Black athletes have demonstrated how racially

derogatory language was in part a result of animosity on the part of White reporters and White

athletes whenever they were defeated or over-shadowed by Black players (Brown et al., 2013;

Powell, 2008). Before basketball’s integration, dozens of all-Black professional teams were

formed before 1950, and some Black teams played against White teams and competed in

championship games over a 10-year span (Adler, 2014). According to Adler (2014), African

Americans were dominant in the championship games over their White counterparts, yet they

were consistently subject to Jim Crow sentiments; even the sports announcers used language

likening the plays of the Harlem Globetrotters, a prominent Black team, to “monkey business”

(para. 17). However, this did not hinder the integration of the National Basketball League

(NBA), and the NBA experienced a quicker route to integration than did professional baseball

and football (Daily History, 2017). The website attributed this to baseball’s Jackie Robinson

breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball just 3 years prior.

The integration of professional basketball also appears to be the first time that race was

downplayed in the media. During the 1950 NBA draft, Boston Celtics team owner Walter

Brown picked a Black All-American college player named Chuck Cooper (Daily History, 2017;

Spears & Khan, 2019). Brown’s co-owner apparently questioned him about Cooper’s race, and

Brown replied he did not care that Cooper was Black (Daily History, 2017). Daily History

(2017) noted, “Boston papers did not even see the need to include Cooper’s race in its covering

of the draft” (para 5). Nonetheless, derogatory language was consistently used by sports

journalists when Black players were on the court, although there is little evidence that early

journalists focused on the upbringings or home neighborhoods of Black athletes. Instead, they

used the stigmatized depictions of the players and their experiences as they attempted to become

30

a part of mainstream athletics, as well as commenting on racial characteristics that delivered a

sense of Black agency. The most common media descriptors that are still a part of modern

sports reporting are that Black athletes have natural athletic abilities, are more aggressive, are

stronger, faster, and bigger, but lack intelligence and intellect—just as Jackie Robinson and other

trailblazers were initially depicted (Brown et al., 2013; Deeb & Love, 2018; Frisby, 2017;

Garbett, 2000). In contrast, the first Black college football player, William Henry Lewis, was

awarded the title of All-American player and team captain, was deemed to be a “superb athlete”

as well as “an outstanding scholar, selected as orator for the (Amherst College) class of 1892”

(Ross, 2000, p. 6). Lewis’s depiction contradicted the common narrative. The NFL’s trend of

employing African American officials, coaches and quarterbacks (a common occurrence by the

1980s) also disrupted the narrative that Black athletes lack intellect (NFL Pro Football

Operations, 2020; Powell, 2008).

Other stereotypes the media helped establish and reinforce are that Black athletes are

inherently dangerous and sexually deviant (Berry & Smith, 2000; Brown et al., 2013; Lapchick,

2019). Conversely, White athletes are traditionally framed as smarter, more disciplined, are

natural leaders, and are more grounded in the game (Brown et al., 2013). From the beginning,

sports writers trended to glorify White male athletes and position them as what every athlete

should strive to be, just as critical race theory points to the norm created by White framing

(Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller, & Thomas, 1995; Delgado & Stefancic, 2001; McChesney, 1989;

Trujillo, 1991). From Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees in the 1920s and early 1930s, to

MLB pitcher Nolan Ryan who played for various teams over a 27-year career from 1966-1993,

the media glorified White players as heroes (Trujillo, 1991). Trujillo’s (1991) elaboration on

Ryan’s media framing as an “ideal image of the capitalist worker, as a family patriarch, as a

31

white rural cowboy” (p. 290) highlighted a Marxist philosophy that firmly and completely

established Ryan as a dominant figure and the poster child for the cultural norm. But White

athletes are not the only ones who benefit from their cultural and media-driven personas. Black

athletes have generated lucrative endorsement deals based on the media that frame them as

outspoken and/or controversial as a result of highly publicized interactions with the media (Blog,

2015; Sitaras, 2014). This is a condition under which the media choose to link Black athletes to

their home neighborhoods—controversy. The other three conditions are when athletes are

extremely talented or achieve extraordinary success like winning championship games, when

they use their platform to draw attention to stigmatized neighborhoods or to a sense of Black

place and space, and when they are accused of an indiscretion or criminal activity.

Outspoken and controversial Black athletes. While stigmatized geographies are

implied in early depictions of Black athletes, they are much more evident in contemporary

media, especially when the players are outspoken and/or controversial, and in some cases, these

actions are a deliberate part of the media’s goal to increase viewership and readership (Shields,

1999). Other scenarios create a space for Black players and their White and non-White agents

to monetize a connection to aggressive, outspoken, and even dangerous from-the-hood

depictions of Black athletes (Powell, 2008; Shields, 1999). This was especially evident in the

late 1990s and early 2000s in the NBA when the athletes themselves started speaking openly

during interviews about their stigmatized communities to help authenticate a bad boy image and

show what they referred to as their street cred (Shields, 1999). Powell (2008) noted that even

players who were otherwise known as quiet accepted the façade of being a loudmouth who could

provide sensationalized headlines because it brought with it “so much, in terms of attention,

social status and of course money” (pp. 191-192). Former NFL player Terrell Owens is an

32

example. His passion and aggressive style of play and interactions with the media were so

controversial that they prompted media-driven interest about his background that resulted in a

number of interviews, a commercial, a documentary, and a docuseries on the Oprah Winfrey

Network (OWN) that highlighted his poor, fatherless, painful upbringing (Brown et al., 2013).

This is an example of controversy or an aggressive persona leading to the media digging deeper

to connect the player to their humble start (Mchezo, 2018; Vanzant, 2013).

Other Black athletes have worked hard to distance themselves from such personas, as

well as other racial and stigmatized community-based stereotypes because they do not want to

jeopardize their success and status (Powell, 2008). Tiger Woods is often described as paving

the way for the participation of Blacks in professional golf just as much as he has confirmed

negative stereotypes faced by African Americans (Brown et al., 2013; Powell, 2008). In what

some call a political as well as a capitalistic decision, Woods distanced himself from the Black

race by accentuating his multi-racial background and describing himself as “Cablanasian”

(Caucasian, Black, and Asian) during an interview (Brown et al., 2013, p. 68). The researchers

argued that once news surfaced about his multiple extra-marital affairs, he was seen as another

stigmatized Black athlete who was out of control and a sexual deviant in need of taming.

Further, media reports could not link Woods to a humble beginnings narrative as a way to try and

explain his indiscretions, because his child neighborhood was not poor or dangerous (Biography,

2021). Instead, journalists delivered messages of a savage, sexually addicted, “privately vulgar”

man (Brown et al., 2013, p.79).

Extraordinary success. While being considered outspoken and/or controversial attracts

place-based narratives, so do Black athletes who accomplish extraordinary success like making it

to the NFL, winning a championship or breaking records. Athletes like Mike Tyson (who

33

became the youngest heavyweight boxing champion of the world at age 20) have generated

stories from trusted sports media sources, the “Bleacher Report” among others, about a

childhood spent in a “high crime neighborhood where bone-crushing fights were a common

occurrence” (Head, 2010, para. 5). Details of Tyson’s upbringing—turning to fighting to fend

off bullies and racking up 38 arrests by the time he was 13, for example—are commonly framed

to explain his extraordinary success as a boxer as well as his inability to stay out of trouble

(Biography, 2020; Head, 2010). Boxing is not alone, for sports media utilizes extreme success

in every sport as a springboard to share as much as possible about star athletes, no matter their

race. The difference is the humble beginning depictions of star athletes are considered the norm

for Black players, while they are considered the exception for White athletes (Carrington, 2010;

Deeb & Love, 2018; Derickson, 2017; Frisby, 2017). Whether it is doing in-depth interviews

about NBA All-Star Bam Adebayo growing up in a trailer park, or the rough New Orleans

community NFL Super Bowl LIV winner Tyrann Mathieu grew up in, or reminding that Tyson’s

ability to fight started as a child from a dangerous neighborhood, the humble beginnings

storyline gets cemented as a dominant narrative that is regularly reinforced by the media (Brown

et al., 2013; Head, 2010; NFL Films, 2016).

Athletes using platforms. A third scenario in which Black athletes are linked to

stigmatized neighborhoods is in evidence when the athlete intentionally calls attention to their

upbringing. A common example is when they return to their childhood neighborhoods to use

some of their earnings to add resources they did not have growing up. NBA elite athlete

LeBron James has received repeated media coverage after returning to his hometown of Akron,